Macroeconomía heterodoxa frente a macroeconomía dominante

Si eres escéptico con uno, también deberías serlo con el otro.

Nunca se oye hablar de "física heterodoxa" y "física dominante", ¿verdad? O "biología heterodoxa" y "biología dominante". Eso simplemente no existe. ¿Por qué? Desde luego, no porque los físicos y los biólogos tengan todo el mundo resuelto; hay muchas incógnitas y teorías que compiten entre sí en esas disciplinas, y las peleas en las aulas de los seminarios pueden llegar a ser francamente crueles. De vez en cuando, estas dos disciplinas son revolucionadas por iconoclastas con ideas nuevas y audaces. Sin embargo, nunca se oye hablar de una disciplina de "biología heterodoxa" o "física heterodoxa" encerrada fuera de la torre de marfil, esperando el día de su triunfo.

Sin embargo, sí se oye hablar mucho de "economía heterodoxa". Se oye hablar de la TMM, de los defensores de las teorías de la "inflación codiciosa" y de los controles de precios, y de los defensores de la política industrial. Puede que incluso oigas hablar de la economía austriaca o de la economía poskeynesiana. No hay una sola economía heterodoxa; hay muchas.

Hay varias razones posibles por las que la economía se diferencia de otras disciplinas en que tiene heterodoxias autodefinidas y autónomas. Una posible razón es la política. La física y la biología se utilizan para crear herramientas tecnológicas, pero la economía se utiliza para hacer política; las cuestiones sobre cómo distribuir los recursos de la sociedad siempre estarán contaminadas por los deseos de los grupos de interés y las ideologías. Es posible que la economía dominante sea dominante no por sus méritos empíricos o su elegancia teórica, sino porque sus preceptos y sus conclusiones se ajustan a los deseos de intereses poderosos. De hecho, si se pregunta a los heterodoxos, a menudo dirán que es así.

Por supuesto, para ser justos, también es posible que grupos de interés politizados que quieren subvertir el paradigma dominante en su propio beneficio creen teorías "heterodoxas" inventadas como herramienta para ganar influencia. Los economistas de la corriente dominante suelen ser demasiado educados para afirmar algo así en voz alta, pero es probable que algunos lo estén pensando.

Pero esta no es la única razón posible por la que la economía tiene heterodoxias formales. Una cosa que notarás es que todas estas heterodoxias son sobre macroeconomía; todas tratan la cuestión de por qué las economías nacionales tienen recesiones y caídas, o por qué crecen y se desarrollan. Ya sabes, las grandes cuestiones. No hay competidores heterodoxos de la teoría de juegos, la economía fiscal o la economía laboral, es decir, las cuestiones más pequeñas y cotidianas del funcionamiento diario de los componentes de la economía. Los heterodoxos te dirán cómo fijar los tipos de interés, pero no cómo gestionar una subasta en línea. Te dirán cómo hacer crecer tu economía, pero no cómo establecer un impuesto sobre el flujo de caja basado en el destino.

Supongo que puede haber razones sociológicas o psicológicas para ello. Quizá los heterodoxos tengan que ir sólo a por las grandes cuestiones porque su única esperanza es atraer la atención del público. O tal vez sólo sean soñadores grandilocuentes. Pero yo creo que es otra cosa; creo que los heterodoxos se centran en lo macro porque es ahí donde reside nuestra mayor ignorancia.

Last November I wrote a post called “Macroeconomics is still in its infancy”. Basically, our current mainstream theories of business cycles just aren’t that useful — they can’t forecast the economy, they have pieces that don’t work, many of the assumptions are fairly absurd, and nobody outside the discipline uses them. The theories missed the 2008 crisis and the Great Recession, and they can’t agree on the causes of the current inflation — in fact, I’d argue that after all these decades, economists still don’t have a good understanding of why inflation happens at all. Some of the most influential and decorated macroeconomists in the business have been known to go back and forth on the question of what causes recessions at all.

Almost none of these problems are due to nefariousness or stupidity on the part of macroeconomists; the issues are that A) macro data is just very sparse and full of dependencies, and B) a macroeconomy is a very complex thing, so building up a full model of it from micro bits and pieces is extremely hard to do. Of course these problems are only compounded for development theory, since development only happens once in each country.

In other words, macroeconomics is sort of in what Thomas Kuhn might call a “pre-paradigm” phase. Unlike in game theory or tax theory etc., humankind has not found the core of an approach that reliably explains key features of business cycles or growth policy. Heterodoxers go for macro because they’re competing to be the paradigm.

Neo-Brandeisian antitrust might seem like an exception to this rule, but it’s really not. In fact, the Neo-Brandeisians are a legal school of thought, not an economic one. The economic theories that explain various harms from excessive market power — such as monopsonies lowering wages — are very mainstream, and economists who are sympathetic to the Neo-Brandeisian cause tend to produce very mainstream-looking research in support of their ideas.

So anyway, I think there are probably both political, sociological, and scientific reasons why heterodox schools of economic thought are pretty much confined to macro. With that in mind, we can ask another question: How should we evaluate heterodox critiques and challenges?

In a recent thread, the writer Jeet Heer calls on mainstream macroeconomists to reflect on their own failings, rather than challenging the deserved “traction” of the heterodox:

But while I think it would be good for mainstream macroeconomists to focus on what they got wrong and try to rectify the situation, I don’t see any sense in embracing heterodox ideas simply because they’re an available alternative. Heterodox ideas deserve the same amount of skepticism and and continuous critical investigation that mainstream theories deserve. “The mainstream failed; we’re not the mainstream, hence we must be right” is a sort of a variant of the Politician’s Fallacy.

One problem in applying skepticism and critical investigation equally is that heterodox and mainstream theories use extremely different methodologies. Generally speaking, mainstream macro uses math, while heterodox macro uses literary text with no math. (There are a few exceptions, but that’s the basic pattern.) Which means that if we judge each theory using its own methodology, mainstream macro will have to pass rigorous quantitative evaluations, while heterodox ideas will “succeed” simply by humans vaguely and intuitively pattern-matching the conditions of the macroeconomy with the blocks of text they read.

It makes little sense for mainstream theories to have to forecast inflation and employment and growth to the nth decimal place in order to be considered useful, while heterodox theories are deemed a success simply because commentators waved their hands at the outside world and said “Sounds legit!”.

In fact, if we apply the “sounds legit” test to mainstream macroeconomics, it comes out looking pretty darn good as regards the recent inflation. Olivier Blanchard, using a simple mainstream Keynesian model of aggregate demand, managed to predict ahead of time that Covid relief spending would cause more inflation than most people realized. No heterodoxer I know of — certainly not the “greedflationers” — made such a bold, early, correct prediction. And a simple textbook model of aggregate supply and aggregate demand would also have predicted that the rise in oil prices in early 2022 due to the Ukraine War would pump up inflation even more.

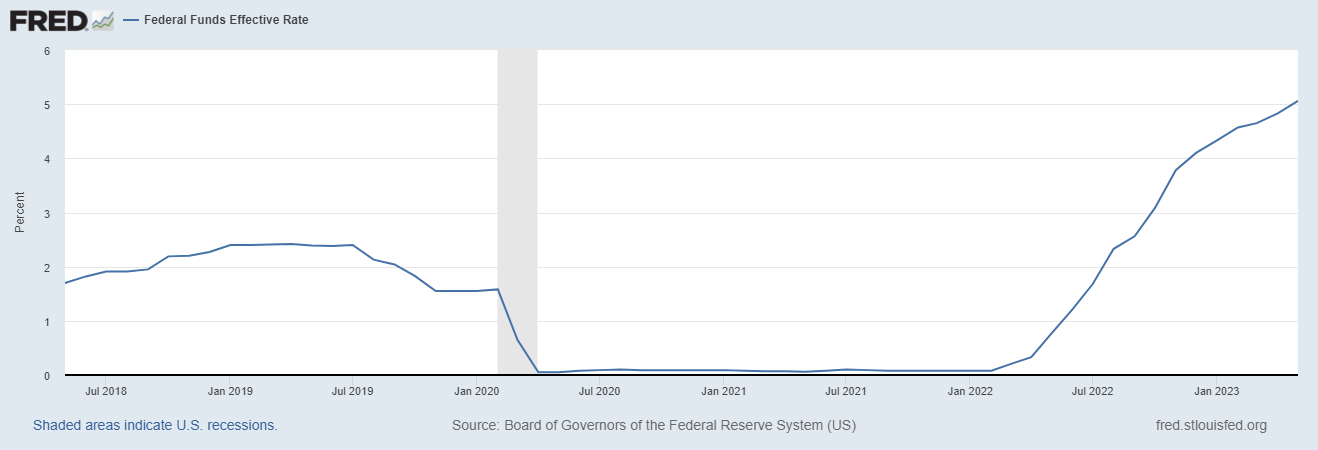

And mainstream macro also gave us most of the solutions to inflation. Mainstream theory says that in order to beat inflation, you raise interest rates and tighten up budget deficits. Well, we did both:

We also released oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, a simple way to boost supply.

The only really “heterodox” thing America did to bring down inflation was to have the G-7 put a cap on the price of Russian oil. That might have weakened the market power of OPEC and sent oil prices lower. But in fact that price cap came after most of the big drop in oil prices had already occurred.

So while I think it’s a good long-term strategy, it’s doubtful the cap did much to bring down inflation in the short term.

Meanwhile, some combination of interest rate hikes, deficit reduction, and the fall in oil prices did the trick. Inflation isn’t yet down all the way to the long-term 2% target, but most measures show it returning to a fairly reasonable level:

And it did all this without causing a recession so far! The labor market has weakened only very slightly, and employment is still at near-record-setting levels:

A big reduction in inflation with no recession and no major rise in unemployment? That’s incredible! What more could you people want from mainstream macroeconomics?

As a result, the Fed is pausing its rate hikes — not declaring “mission accomplished”, since it’ll still keep rates elevated for a while, but at least declaring that the most dangerous and difficult part of the inflation fight is over.

To sum up: Mainstream macroeconomics correctly predicted the recent inflation, and gave us the tools that looked to have solved much of the problem. Heterodoxers, meanwhile, stood on the sidelines, calling for price controls that never happened and complaining into the void about corporate greed.

Of course, this general hand-waving, heuristic approach is how heterodox people judge their own success. By that method, mainstream macro comes out looking great in the current inflation. It’s only once you apply the mainstream’s own more rigorous critical evaluation and quantitative tests that mainstream theories start to look less spectacular.

For example, Blanchard may have predicted inflation, but he incorrectly predicted that it would manifest in higher wages rather than higher consumer prices. And most macroeconomists expected rate hikes to reduce inflation by raising unemployment; the fact that they haven’t so far is a big surprise, and the reason remains a mystery.

So I’m still somewhat unsatisfied with mainstream theory’s performance here. But when we do an apples-to-apples comparison against heterodox ideas like “greedflation” or MMT, the latter come out looking worse this time around. Critics of the mainstream, like Jeet Heer, ought to apply such apples-to-apples comparisons of success and failure, instead of insisting on holding the mainstream to astronomically higher standards.

No estoy tratando de decir que la economía heterodoxa esté llena de basura, o que no la necesitemos (aunque ciertas personas enfadadas en línea sin duda interpretarán mis declaraciones de esa manera a pesar de todo). De hecho, creo que el pensamiento heterodoxo ayudó a mejorar la corriente dominante tras la crisis financiera, reintroduciendo en el discurso ideas como el "Momento Minsky". Y creo que incluso ahora se está gestando una verdadera revolución en la teoría del crecimiento y el desarrollo, con la idea heterodoxa de la política industrial empezando a hacer una gran reaparición.Pero lo que digo es que deberíamos aplicar a las ideas heterodoxas el mismo nivel de escepticismo y crítica que aplicamos a las ideas dominantes. Obligar a las teorías dominantes a someterse a las duras pruebas de la torre de marfil, mientras que las ideas heterodoxas se juzgan un "éxito" simplemente porque unos pocos periodistas creíbles creen en ellas lo suficiente como para hacer vídeos cutres sobre ellas, hace un flaco favor a la búsqueda de una comprensión real. Y necesitamos desesperadamente perseguir la comprensión real tan seria y vigorosamente como podamos, aunque sea realmente difícil, porque hay mucho en juego: puestos de trabajo, salarios, ingresos, medios de subsistencia y las propias vidas.

https://www.noahpinion.blog/p/heterodox-vs-mainstream-macroeconomics

"Las matemáticas de la macro moderna son, en realidad, bastante fáciles. Contar la historia detrás de las matemáticas, interpretarlas y hacer las conclusiones útiles para la política económica son las tareas verdaderamente difíciles" (sobre todo para los que no usan matemáticas)

Ayer Noah Smith, hoy Cochrane. De mal en peor

https://johnhcochrane.blogspot.com/2023/06/the-fed-and-phillips-curve.html

https://twitter.com/jfjimenoserrano/status/1669644731532419074

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario