. General assessment of the macroeconomic situation

Introduction

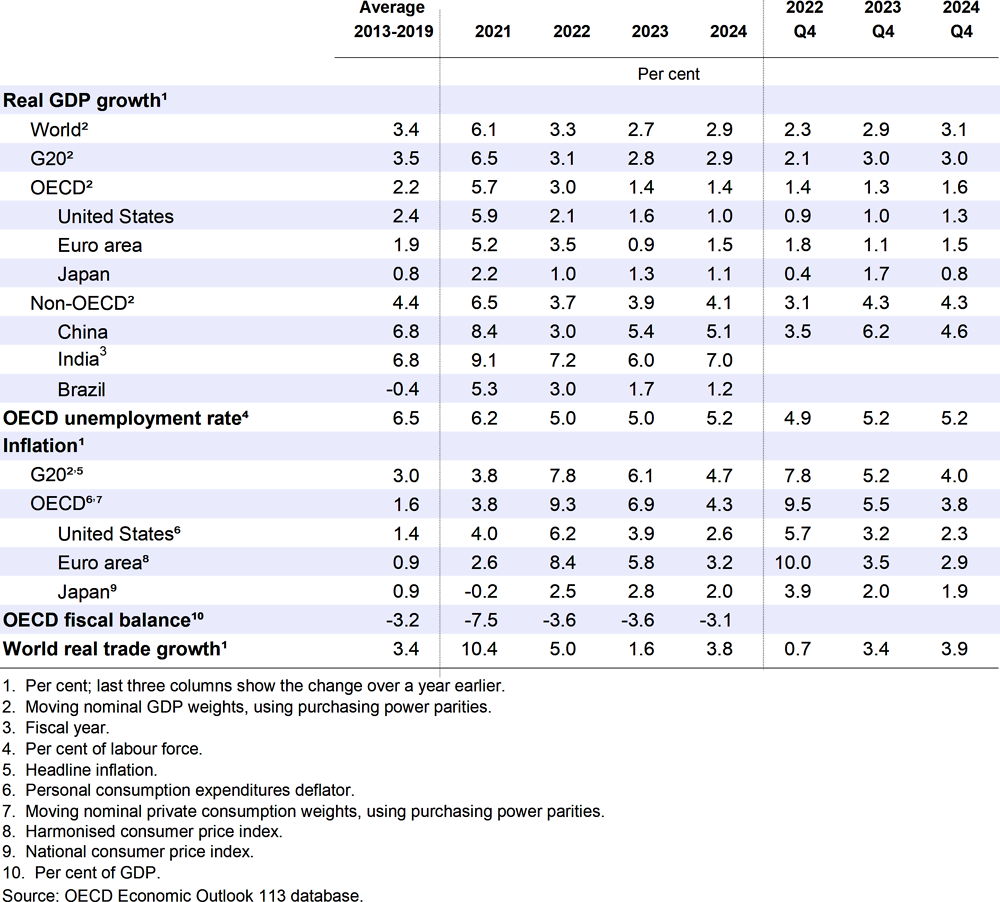

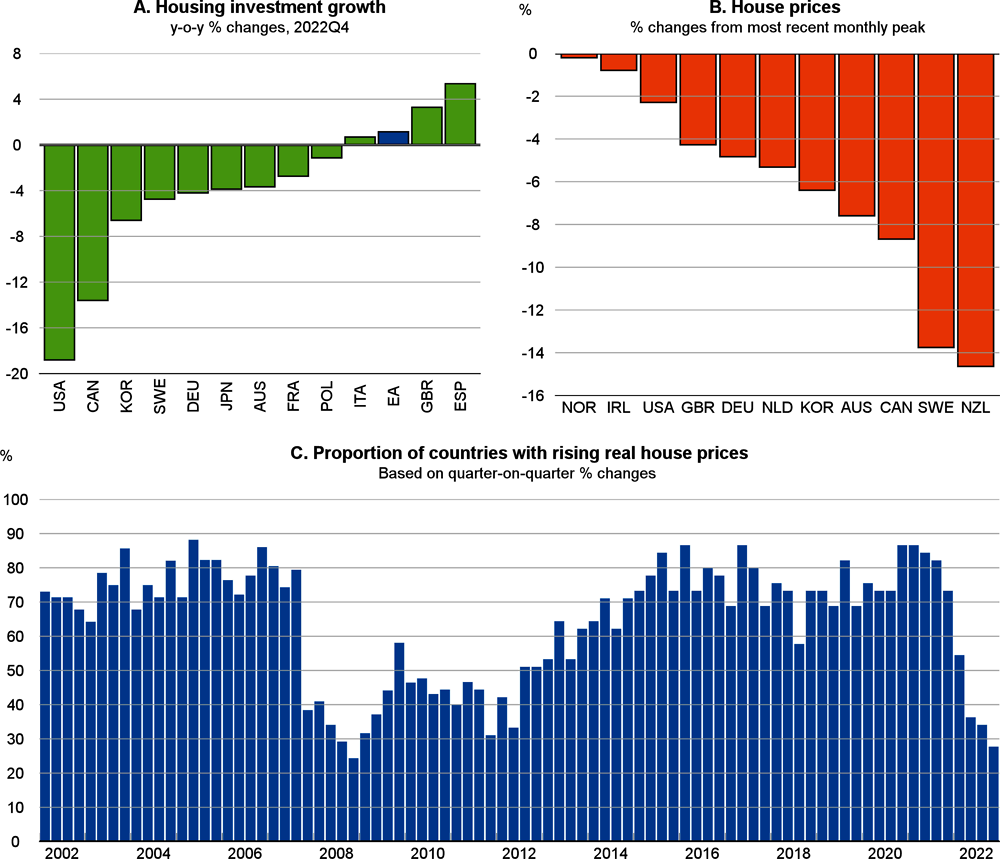

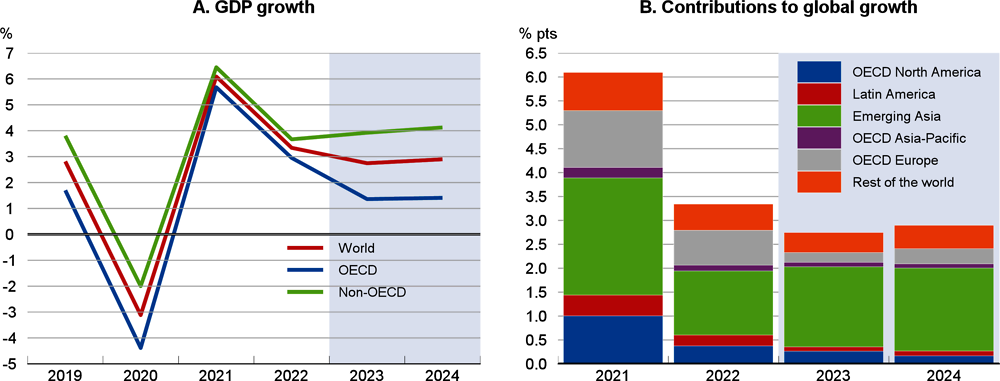

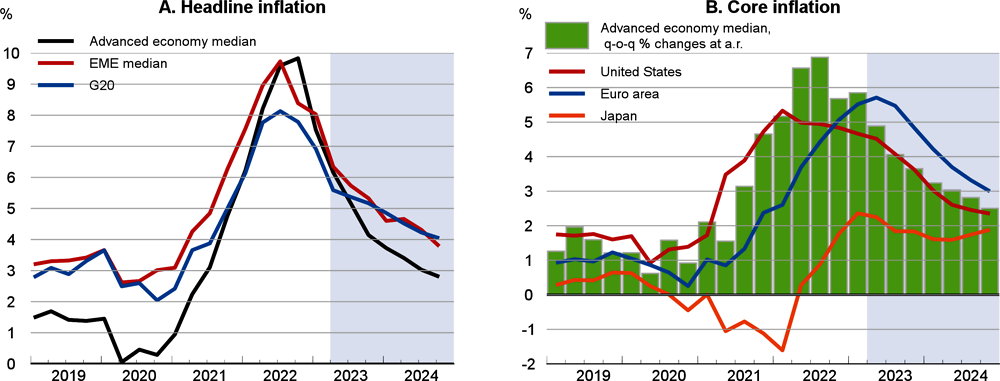

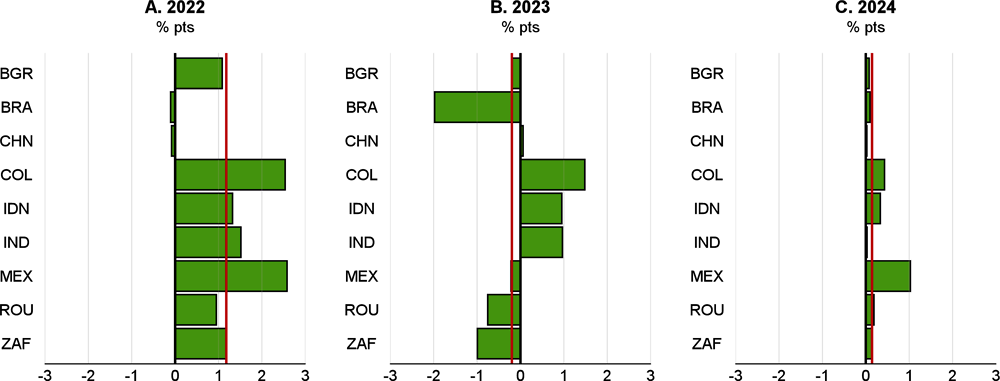

La evolución económica mundial ha empezado a mejorar, pero el repunte sigue siendo frágil. La bajada de los precios de la energía está contribuyendo a reducir la inflación general y a aliviar las tensiones en los presupuestos familiares, la confianza de las empresas y los consumidores está recuperándose de sus bajos niveles, y la plena reapertura de China, antes de lo previsto, ha dado un impulso a la actividad mundial. Al mismo tiempo, la inflación subyacente se muestra persistente, como reflejo del aumento de los beneficios en algunos sectores y de las presiones aún elevadas sobre los costes en unos mercados laborales resistentes. El impacto de la subida de los tipos de interés en todo el mundo también se deja sentir cada vez más, sobre todo en los mercados inmobiliarios y financieros. Han empezado a aparecer signos de tensión en algunos segmentos del mercado financiero a medida que los inversores reevalúan los riesgos, y las condiciones crediticias se están endureciendo. Se prevé que el crecimiento del PIB mundial se modere del 3,3% en 2022 al 2,7% en 2023, antes de subir a un todavía moderado 2,9% en 2024. La política monetaria restrictiva limitará el crecimiento de la demanda durante algún tiempo, y los efectos plenos del endurecimiento de la política en 2022 no aparecerán hasta finales de este año o principios de 2024. Se prevé que la inflación anual de los precios al consumo en las economías del G20 disminuya del 7,8% en 2022 al 6,1% en 2023 y al 4,7% en 2024, favorecida por la bajada de los precios al por menor de la energía y los alimentos, la moderación de las presiones de la demanda y la reducción de los estrangulamientos de la oferta. Se prevé que la inflación subyacente se mantenga relativamente estable, pero que disminuya gradualmente hacia el objetivo en las principales economías avanzadas a finales del próximo año.

Significant uncertainty about economic prospects remains, and the major risks to the projections are on the downside. One key concern is that inflation could continue to be more persistent than expected. Significant additional monetary policy tightening may then be required to lower inflation, raising the likelihood of abrupt asset repricing and risk reassessments in financial markets. A related concern is that the strength of the impact from the monetary policy tightening that has already occurred is difficult to gauge after an extended period of very accommodative policy and the speed at which policy interest rates have subsequently been raised. While a cooling of overheated markets and moderation of credit growth are standard channels through which monetary policy normally takes effect, the impact on economic growth could be stronger than expected if tighter financial conditions were to trigger stress in the financial system and undermine financial stability. Sharp changes in the market value of bond portfolios may further expose liquidity and duration risks. Rising household and corporate debt-service burdens and the greater potential for loan defaults also raise credit risks at banks and non-bank financial institutions, and could result in a further tightening of lending standards. Tighter than expected global financial conditions could also intensify vulnerabilities in emerging-market economies, adding to debt servicing costs and capital outflows, and reducing credit availability for borrowers relying on foreign lenders. Another key downside risk to the outlook relates to the uncertain course of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine and the associated risks of renewed disruptions in global energy and food markets. On the upside, reduced uncertainty from an early end to the war, easier-than-expected financial conditions, more robust labour force growth, and greater use of accumulated savings by households and businesses would all improve growth and investment prospects. However, the impact of these individual shocks on inflation could vary.

The need to durably lower inflation, adjust fiscal policy support and revive sustainable growth creates difficult challenges for policymakers.

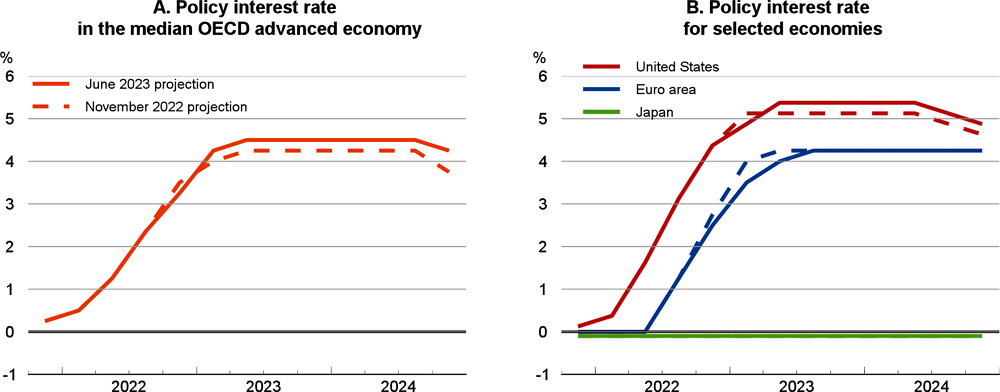

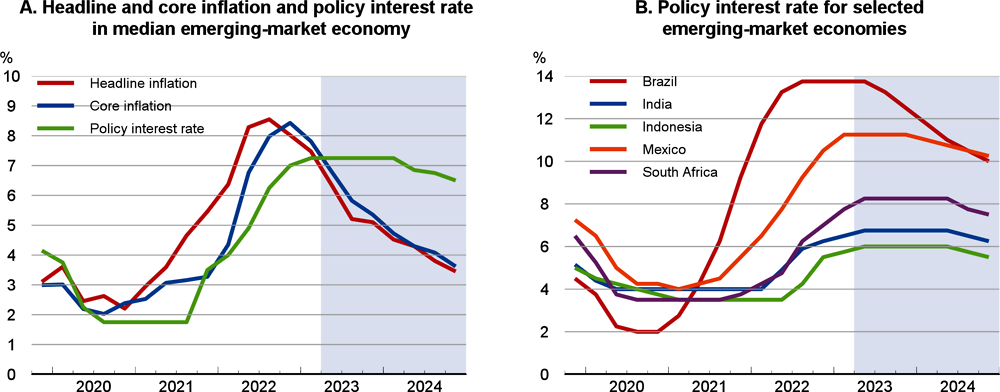

Monetary policy needs to remain restrictive until there are clear signs that underlying inflationary pressures are durably reduced. This may require additional interest rate increases in economies in which high core inflation is proving persistent. Policy decisions will need to be carefully calibrated given uncertainty about financial market developments and the need to take stock of the cumulated impact of past interest rate increases. If additional financial market stress occurs, central banks should make full use of the set of financial policy instruments available to enhance liquidity and minimise contagion risks. Clear communication will be necessary to minimise uncertainty about apparent conflicts between the pursuit of price stability and financial stability mandates. Policy space in most emerging-market economies is constrained by the need to keep inflation expectations anchored and tight global financial conditions. In the event of exchange rate pressures, countries should let their currencies adjust as much as possible to reflect underlying economic fundamentals. However, temporary foreign exchange interventions or restrictions on capital movements could be employed to mitigate sudden moves that generate severe risks to domestic financial stability.

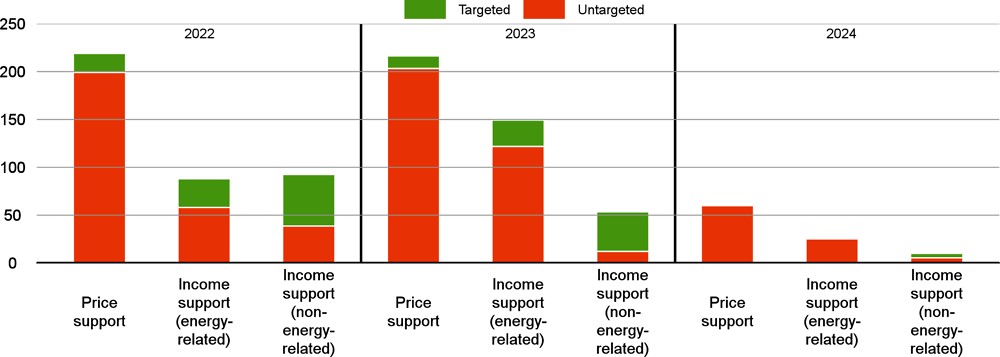

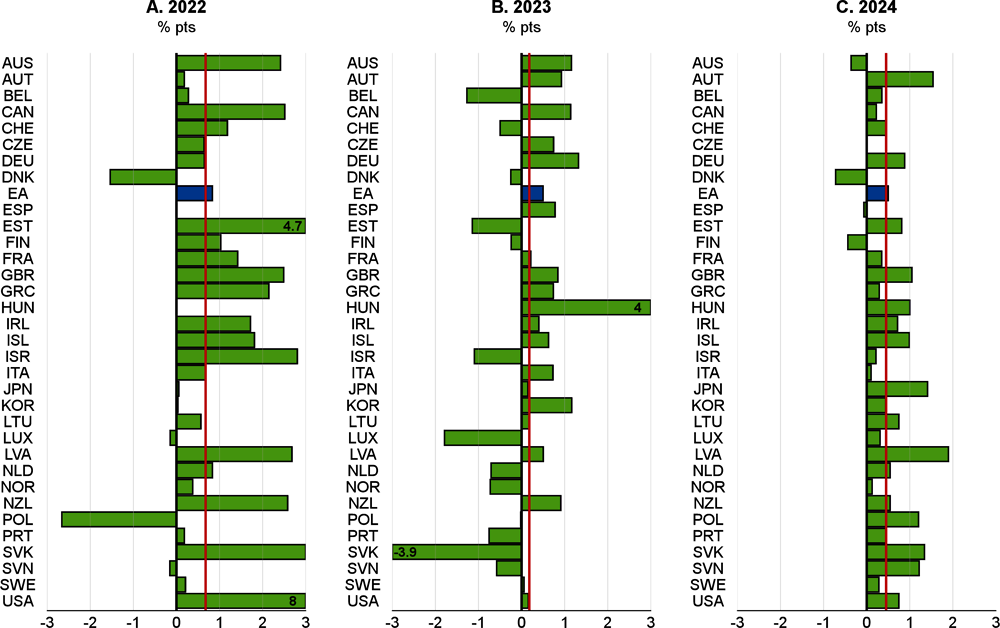

Ensuring the sustainability of the public finances has become more challenging due to the multiple impacts of the pandemic, the war and energy shocks. Almost all countries have higher budget deficits and debt levels than before the pandemic, and many face rising future spending pressures from ageing populations, the climate transition and the growing burden of servicing public debt given higher interest rates. Careful choices are needed to preserve scarce budget resources for future policy priorities and to ensure debt sustainability. Credible fiscal frameworks setting out future expenditure and tax plans are needed to provide clear guidance about the medium-term trajectory of the public finances. In the near term, with food and energy prices having declined, and minimum wages and welfare benefits having now been permanently increased to take account of past inflation in many countries, fiscal support to mitigate the impact of higher food and energy prices should become targeted on vulnerable households inadequately covered by the general social protection system. This would preserve incentives to reduce energy use, help to limit aggregate demand pressures on inflation, and better align fiscal and monetary policies.

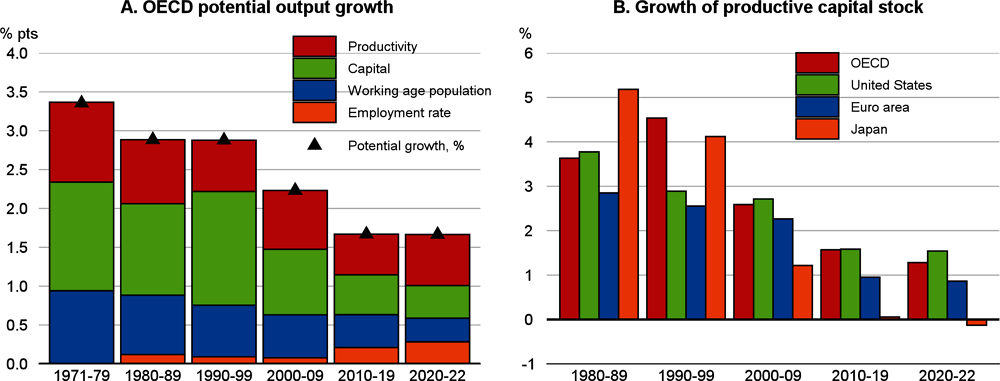

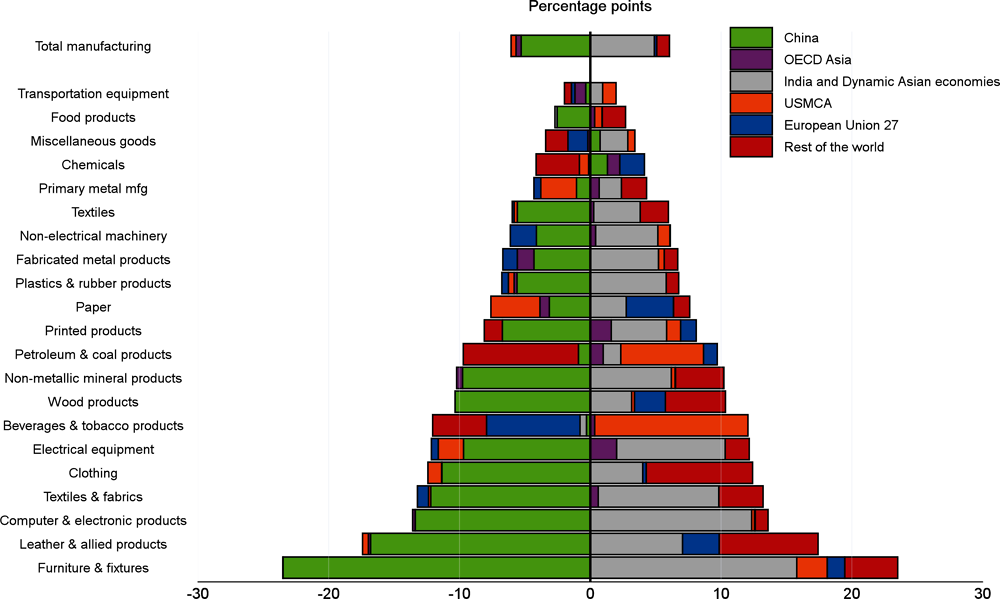

La coyuntura, el descenso a largo plazo de las tasas de crecimiento potencial y los acuciantes retos futuros, como el envejecimiento de la población y la transición climática, apuntan a una clara necesidad de reformas estructurales ambiciosas que impulsen la oferta. Reactivar los esfuerzos de reforma para reducir las restricciones en los mercados de trabajo y de productos, y reforzar la inversión, la participación de la mano de obra y el crecimiento de la productividad mejoraría los niveles de vida sostenibles y reforzaría la recuperación de la actual ralentización. Aumentar el dinamismo de las empresas, reducir los obstáculos al comercio transfronterizo y a la migración económica, y fomentar unos mercados laborales flexibles e integradores, entre otras cosas mediante la mejora de las cualificaciones y la eliminación de los obstáculos que aún dificultan la participación de la mano de obra, son ámbitos políticos clave en los que unas reformas bien diseñadas contribuirían a impulsar la competencia, reactivar la inversión y aliviar las restricciones de la oferta.

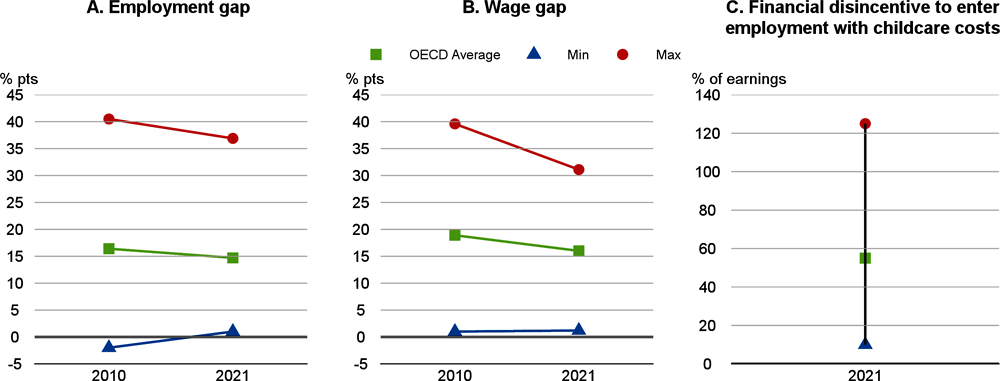

Gender employment and wage gaps have generally narrowed at a relatively modest pace over the past decade, calling for further action across a broad range of policy areas to strengthen participation, skills and opportunities for women. Such action would improve growth prospects, make them more inclusive and ensure that all talent is utilised effectively. Key priorities include improving access to affordable high-quality childcare, incentivising better sharing of parental leave between parents, reforming tax-benefit systems to remove disincentives for women to participate in labour markets, and encouraging gender equality within firms.

The series of shocks to the global economy in recent years and longer-term global challenges such as climate change underline the need for enhanced international cooperation. At the same time, geopolitical tensions have increasingly hindered cross-border flows of goods, services, capital and labour, and contributed to food insecurity for many countries. The rise in debt distress among low-income countries makes it particularly urgent that creditor countries and institutions take joint action – building on the initial steps taken under the G20 Common Framework – to ensure that debt burdens are sustainable, and avoid the risk of a lost decade of development for many low-income countries. More generally, in an interconnected world, countries have to find ways to ensure that frictions in some areas do not prevent progress being made on issues of common interest, including climate change mitigation, open markets, economic security, and responding to pandemics.

After weak global growth in 2022, there are signs of improvement in 2023

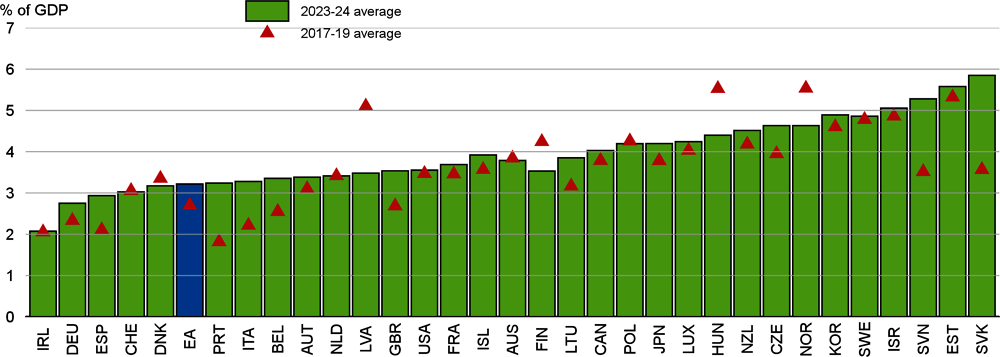

El crecimiento mundial se desaceleró sustancialmente a lo largo de 2022, tanto en las economías avanzadas como en las emergentes (gráfico 1.1, panel A). El fuerte repunte de los precios de los alimentos, los fertilizantes y la energía tras la invasión rusa de Ucrania se sumó a los ya considerables aumentos de 2021, elevando considerablemente la inflación general en casi todos los países y generando descensos de la renta real disponible de los hogares. La relación entre los gastos agregados en energía de uso final de la OCDE y el PIB aumentó bruscamente en 2022, alcanzando el nivel más alto desde principios de la década de 1980, aumentando los costes para las empresas y erosionando el poder adquisitivo de los hogares (OCDE, 2022b). El endurecimiento significativo de la política monetaria por parte de casi todos los principales bancos centrales hizo subir los tipos de interés oficiales y empezó a pesar sobre los componentes del gasto sensibles a los intereses. La ralentización en las economías de la OCDE estuvo liderada por la inversión en vivienda, que se contrajo durante 2022, pero el crecimiento del gasto de los consumidores y de la inversión empresarial también disminuyó a lo largo del año. En el cuarto trimestre de 2022, el crecimiento mundial se había ralentizado hasta una tasa anualizada de tan solo el 2%, y el crecimiento a lo largo del año cayó hasta el 2¼%, algo más de la mitad del ritmo observado durante 2021. La producción disminuyó en 15 economías de la OCDE en el cuarto trimestre, la mayoría de ellas en Europa. Los resultados también fueron relativamente débiles en las economías de Asia-Pacífico, con una actividad en China que sigue frenada por una oleada de infecciones por COVID-19 y restricciones de salud pública. El PIB de China creció sólo un 3% en 2022, menos que en cualquier año de las últimas cuatro décadas, con la excepción de 2020, que se vio aún más gravemente afectado por la pandemia.

Economic indicators in the first months of 2023 have improved, with global GDP growth picking up to an annualised rate of just over 3% in the first quarter, despite mixed outcomes across countries. Growth rebounded in Brazil, China, India and Japan, but slowed in the United States, and there was only a modest output rise in the euro area and the United Kingdom. Business surveys have improved markedly relative to late 2022, particularly in the services sector (Figure 1.1, Panel B) and consumer confidence indicators in major economies have also begun to recover from the very low levels seen last year.

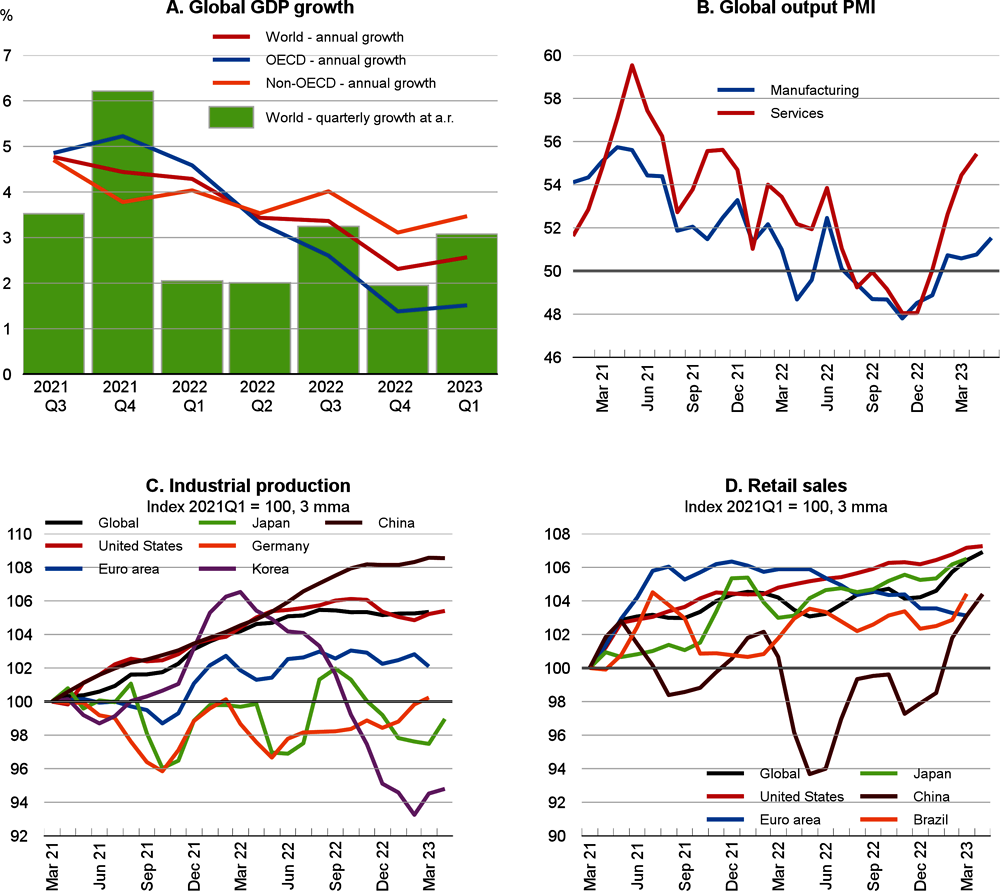

The improvement in the early part of this year is driven to some extent by declines in energy prices and better prospects for China. Energy commodity prices have fallen sharply since last summer, with a particularly marked decline in the price of natural gas, above all in Europe (Figure 1.2). However, this has yet to be fully reflected in lower retail prices in many countries. The spot prices of oil and coal have also come down a long way from the peaks reached after the invasion of Ukraine last year, easing pressures on households and companies. Even so, prices generally remain higher than seen prior to the pandemic. China’s earlier-than-expected reversal of its zero-COVID policy in December 2022, combined with a loosening of both fiscal and monetary policy, has also boosted business sentiment, as stronger growth of the Chinese economy will have positive benefits in the Asia-Pacific region and more widely.

Recent monthly activity indicators have been mixed. The manufacturing sector is still weak (Figure 1.1, Panel C), notably in several Asian economies, in part due to subdued tech sector activity. In most economies, the improvement in early 2023 has been more apparent in services sectors, helped by a rebound in consumer demand in China and solid growth in the United States (Figure 1.1, Panel D). However, demand for durable goods remains soft, in part reflecting the greater sensitivity of such spending to financial conditions.

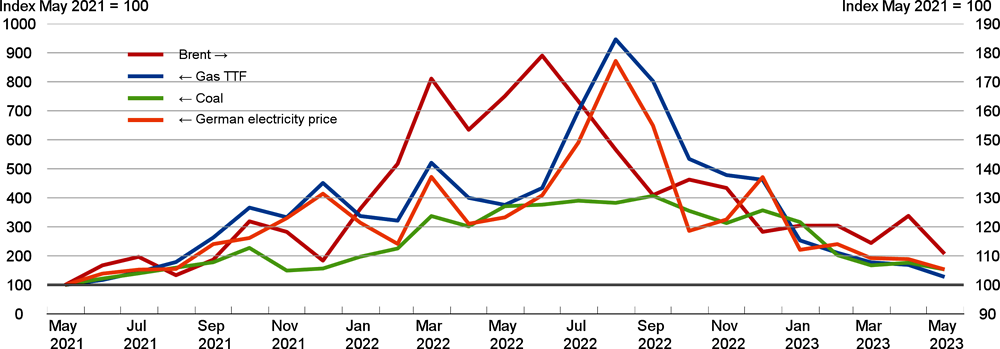

The impact of tighter monetary policy is becoming increasingly visible in property markets. Housing investment declined in all the large OECD economies in the second half of 2022. In the fourth quarter of 2022, housing investment in the OECD economies with available data was 7½ per cent weaker than a year earlier, with the decline approaching 19% in the United States and exceeding 13% in Canada (Figure 1.3, Panel A). Housing investment continued to contract in the United States and Canada in the first quarter of 2023. House prices have also begun to adjust to policy tightening, with nominal price declines now underway in many economies (Figure 1.3, Panel B), and even larger real price declines given high consumer price inflation. Price adjustments have been relatively quick in countries with elevated price-rent ratios, high household debt, and a sizeable share of adjustable-rate mortgages. Price changes have been less marked in countries with strong population growth and a large share of mortgages at fixed borrowing rates (OECD, 2022b). Even so, many mortgages have rates that float or are fixed for only a few years, and mortgage-holders will increasingly be faced with rising payments if mortgage rates remain at their new higher levels. Past experience has shown that swings in real house prices are often associated with business cycle fluctuations (Hermansen and Röhn, 2017; Cavalleri et al., 2019; Figure 1.4, Panel C), both because of the substantial drag on economic activity from lower investment and pressures on household finances and balance sheets, and because of associated strains in the financial sector.

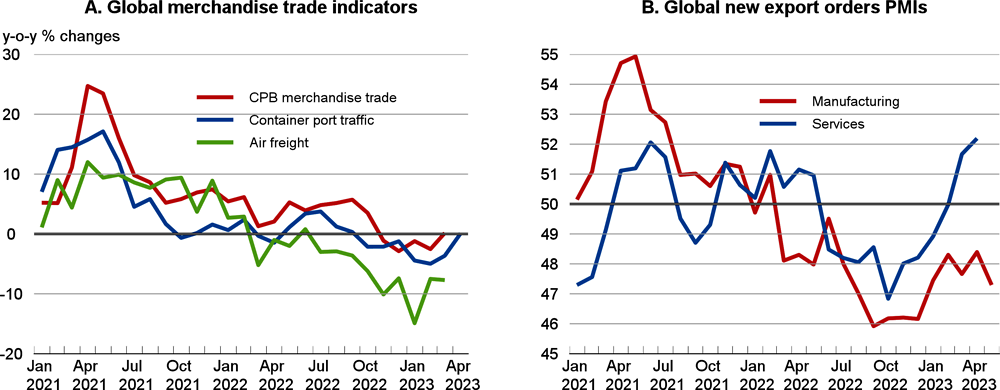

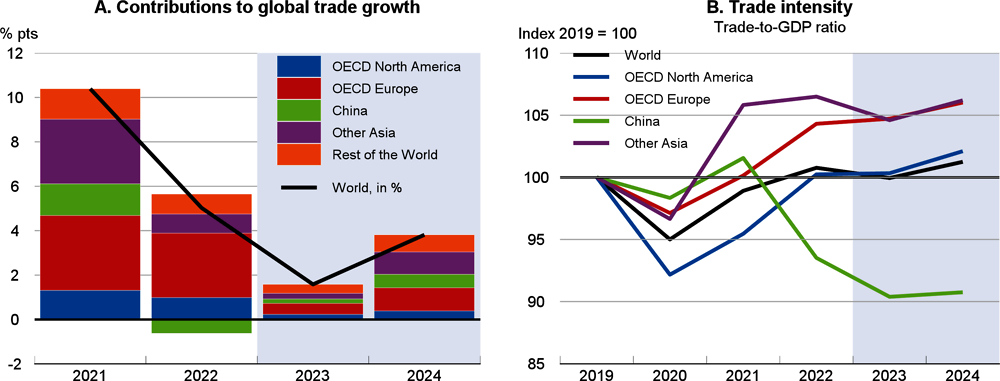

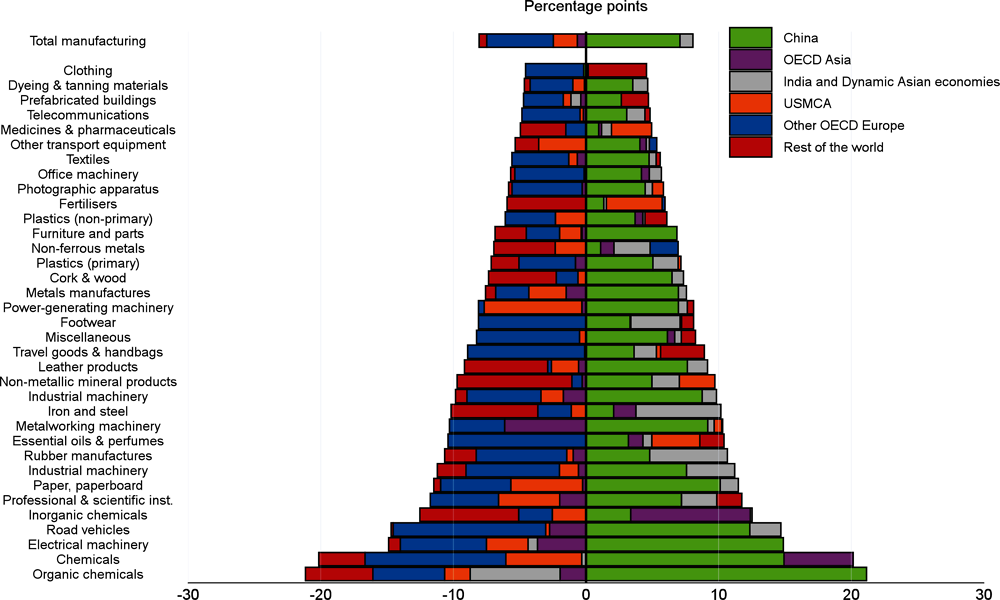

El crecimiento del comercio mundial fue relativamente sólido en 2022, un 5%, a pesar de la guerra en Ucrania, las elevadas tensiones geopolíticas y los precios de las materias primas, y la apreciación generalizada del dólar. El comercio se vio respaldado por la disminución gradual de los cuellos de botella de la oferta, la continua recuperación de la demanda de servicios de viajes por parte de los consumidores y el levantamiento gradual de las restricciones de viaje relacionadas con el COVID, especialmente en Asia. A pesar del crecimiento anual relativamente fuerte, el comercio de bienes y servicios se tambaleó en el cuarto trimestre de 2022, con un descenso trimestral anualizado del 7% en los volúmenes comerciales. El endurecimiento de la política monetaria, la ralentización de la producción industrial, los elevados niveles de existencias y la desaceleración del ciclo de los semiconductores redujeron la demanda. Además, una nueva oleada de infecciones por COVID-19 en China restringió el comercio dentro de Asia. Los volúmenes del comercio mundial se recuperaron parcialmente en el primer trimestre de 2023, con un aumento estimado del 1,8% (a tasa anualizada), pero el comercio mundial de mercancías siguió siendo muy débil. Los precios del transporte y los volúmenes de envío son débiles y las encuestas sobre nuevos pedidos de exportación de manufacturas se mantienen en general en niveles bajos, aunque los pedidos de exportación de servicios siguen mejorando (Figura 1.4). Ahora que los cuellos de botella de la oferta mundial se han atenuado en gran medida y China se ha reabierto, la moderada demanda de productos manufacturados y materias primas, que representan casi el 80% de los volúmenes comerciales totales, pesará sobre el crecimiento del comercio mundial.

Despite war-related trade restrictions and the potential risk to the supply of key agricultural products from Ukraine, global food exports have held up relatively well. Exports of wheat, maize and barley from Ukraine fell by 9.1% in 2022, to 41.3 million tonnes, but the Black Sea Grain Initiative has facilitated over 16 million tonnes of approved food shipments from Ukraine in 2022 and more than 15 million tonnes in the first five months of 2023. Accelerating the food transported through this initiative, by supporting inspection and trade insurance, would increase Ukraine’s exports to its traditional markets in the Middle East and Africa and enhance food security in these countries.1

Financial market conditions remain tight and volatile

The impact of monetary policy tightening is increasingly being reflected in financial market developments, particularly credit conditions and the prices of long-term fixed-income assets. Significant stress has also appeared in parts of the banking system, heightening market volatility, though this has not led to a substantial generalised further tightening of financial conditions.

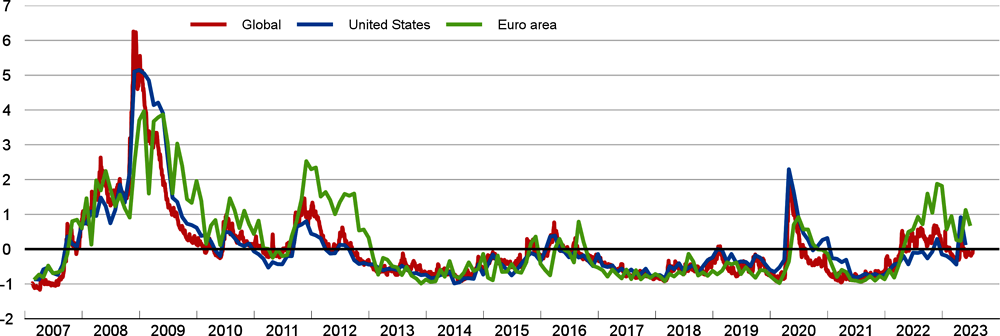

The failure of some regional US banks in recent months and the forced takeover of Credit Suisse, a global systemically-important bank, quickly generated tensions in global banking markets. Bank equity indexes fell sharply, and banks’ credit default swap (CDS) spreads soared by some 60 to 80 basis points in the United States and the euro area. While noticeable, the increase was significantly lower than at the peak of the global financial crisis in 2008. Timely policy measures to deal with the failing institutions and address banks’ liquidity pressures have helped to stabilise financial conditions (Figure 1.5), but significant liquidity, duration and credit risks remain in segments of financial markets.

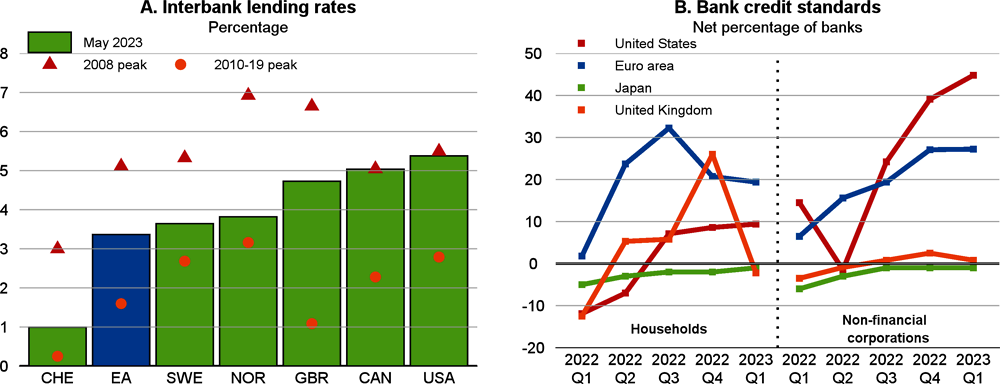

The rising cost of funding for banks (Figure 1.8, Panel A) and the need to further strengthen capital and liquidity buffers are likely to result in more restrictive credit conditions. Bank lending standards have already tightened substantially in most major advanced economies, particularly in the United States and in the euro area (Figure 1.8, Panel B), although not in Japan, where monetary policy remains accommodative. In the United States, lending standards have tightened at a faster pace than in previous tightening cycles, but have not yet reached the peaks seen at the height of the global financial crisis. Changes in policy interest rates in other countries have been quickly transmitted to deposit rates and banks have passed through the high cost of funding to lending rates, leading to a slowdown of credit growth in many economies (Box 1.1). New loans for house purchases have been falling sharply in several OECD countries, including the largest European economies.

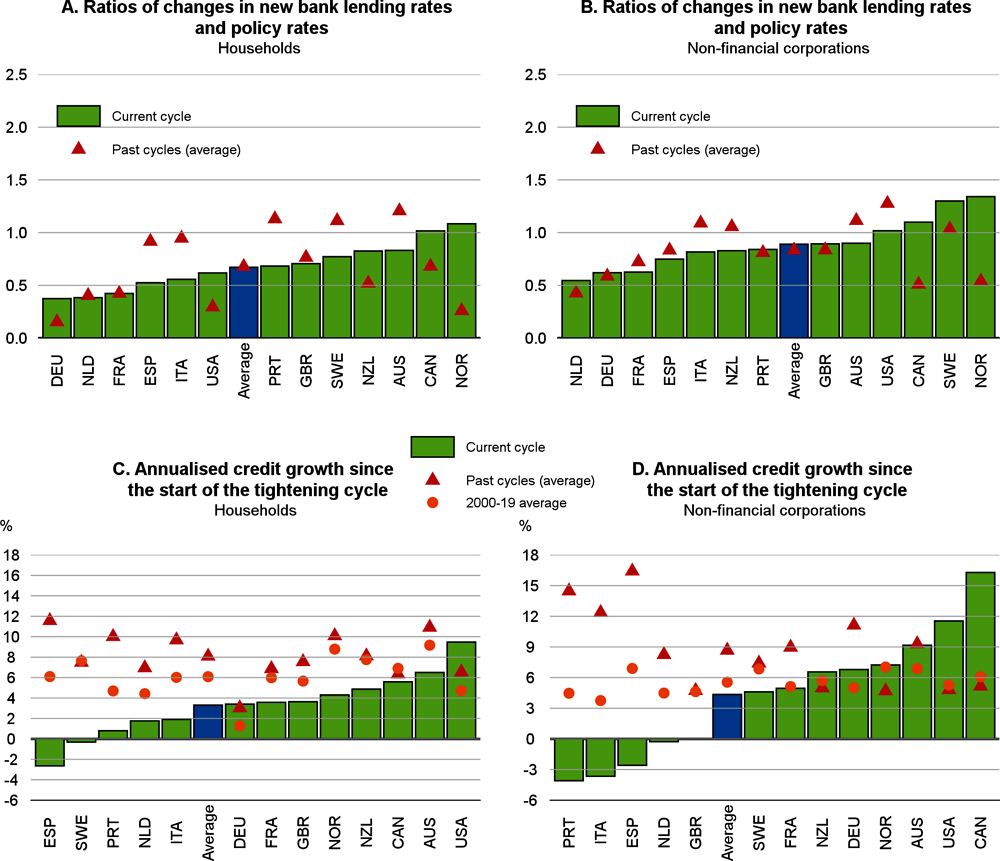

The impact of monetary policy on financing conditions for households and firms is a key channel for the transmission of changes in the policy stance.1 Ultimately, the effectiveness of monetary policy depends on the speed and extent to which changes in policy rates are passed through to economic agents. Rising policy rates have already been quickly transmitted to money market rates and bank funding costs over the past year, with inter-bank interest rates and deposit rates reaching levels not seen since the peak of the global financial crisis in some countries. This Box assesses the extent to which these developments are affecting financing conditions for households and companies. The analysis suggests that changes in policy rates in the advanced economies are being quickly reflected in bank credit conditions, with transmission occurring at a broadly similar pace to that seen in past tightening cycles. The pass-through of monetary policy to corporate bond yields appears to be taking place more slowly.

Comparing movements in policy rates and the interest rates charged on new bank loans provides one means of assessing the strength and speed of monetary policy pass-through.2 Banks generally base the lending rates they charge to firms and households on their own funding costs, plus a mark-up.3 On average, across countries, banks have swiftly passed through the higher cost of funding to economic agents (Figure 1.6, Panels A and B), especially to non-financial corporations, where bank lending rates have on average increased almost one-to-one with policy rates. Transmission is occurring at a similar pace to past tightening cycles on average, but with significant variation across countries. The largest relative changes in new bank lending rates are in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Norway and Sweden, in some cases reflecting an earlier start to policy tightening.

In some countries, including Germany, Sweden and the United Kingdom, the increase in bank lending rates has outpaced the changes in deposit rates, pointing to a somewhat slower pass-through of monetary policy to savers than borrowers.4 However, deposit rates have started to rise more rapidly recently, with banks trying to counteract tighter liquidity conditions and an acceleration in deposit outflows by offering higher rates to their customers. Euro area data suggest that bank lending rates charged on short-term loans to non-financial corporations have generally increased faster than these on lending at longer maturities, while lending rates on consumer loans to households have risen less than rates on loans for house purchases.

Fast-rising bank lending rates have been associated with a slowdown in the pace of nominal credit growth (Figure 1.6, Panels C and D). The slowdown has been somewhat more pronounced for credit to households, although credit to firms has contracted in a handful of countries. In the majority of the countries considered, credit growth has been more muted than at similar points in previous tightening cycles, and also lower than on average over 2000-19, particularly in the case of credit to households. The available evidence thus suggests that monetary policy transmission is proving at least as effective as in past tightening cycles. The slowdown in credit growth is even stronger if measured in real terms, as inflation has been higher in most countries than in many previous monetary tightening cycles.

Bank lending surveys suggest that slowing credit growth and higher lending rates observed in the advanced economies reflect a combination of tighter credit standards and falling credit demand. While data are only available for a few countries, banks overwhelmingly report a tightening of credit standards in recent quarters, especially for mortgage lending in the euro area and for lending to non-financial corporations in the United States. Credit standards for mortgage lending have also tightened in the United Kingdom, albeit by less. Surveys point to a sharp decline in credit demand as well, especially for house purchase in the euro area and in the United States, reflecting a range of factors, including weak income growth. In the euro area, the decline of credit demand for house purchases is similar to that seen during the global financial crisis. Banks expect a further deterioration of credit conditions in the second quarter of 2023, especially for loans to households, again overwhelmingly reflecting tighter credit standards and, in the euro area and in the United States, a further decline of credit demand.

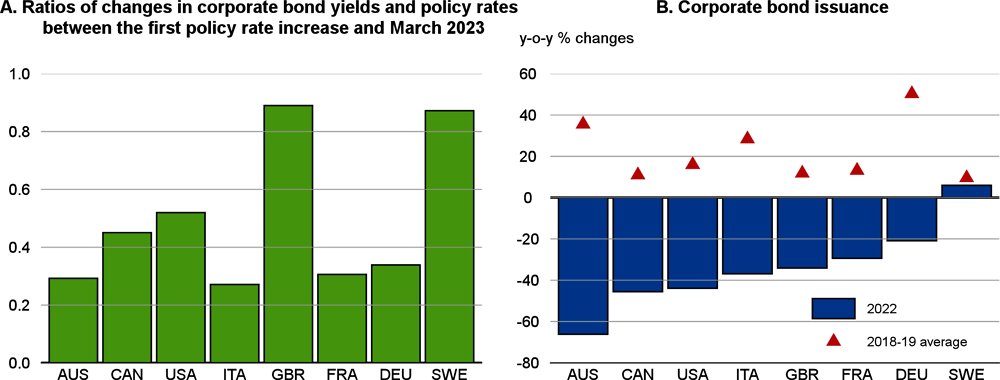

Rising policy rates have also been reflected in the cost and quantity of market-based debt available to firms. Yields on corporate bonds have risen in recent quarters in most advanced economies (Figure 1.7). The pass-through of monetary policy to corporate bond yields appears to be generally slower than for bank lending rates. In addition, corporate bond issuance has recently dried up in most economies. There is also evidence from euro area firm-level data that riskier firms have reduced their bond issuance since June 2022 more vigorously than other firms (Lane, 2023). Due to lags in the transmission of monetary policy, the effect of all of the recent increases in policy rates on financing costs has yet to fully materialise. As banks continue to pass through higher policy rates to households and corporates, financing conditions could tighten further in coming quarters, weighing on economic activity.

← 1. The literature emphasises three main transmission channels of monetary policy: the interest rate channel, the asset price channel and the credit channel (Bernanke and Gertler, 1995; Mishkin, 1996). The interest rate channel transmits changes in policy rates to retail lending and deposit rates via money markets, causing adjustments to investment and saving decisions. The asset price channel works through the prices of bonds, stocks and real estate, changing the effective cost of capital and the net worth of households and firms and thus affecting consumption and investment. Finally, the credit channel transmits monetary policy signals by influencing the balance sheets of banks, firms and households, and hence credit supply and demand.

← 2. In addition to changes in the monetary policy stance, bank lending rates can also reflect other factors, including exogenous changes in demand and supply conditions.

← 3. The size of the mark-up depends on several factors, including banks’ business models, balance sheet and leverage conditions, the degree of competition in the banking system, business cycle conditions and banks’ appetite for risk (Maravalle and Gonzalez Pandiella, 2022).

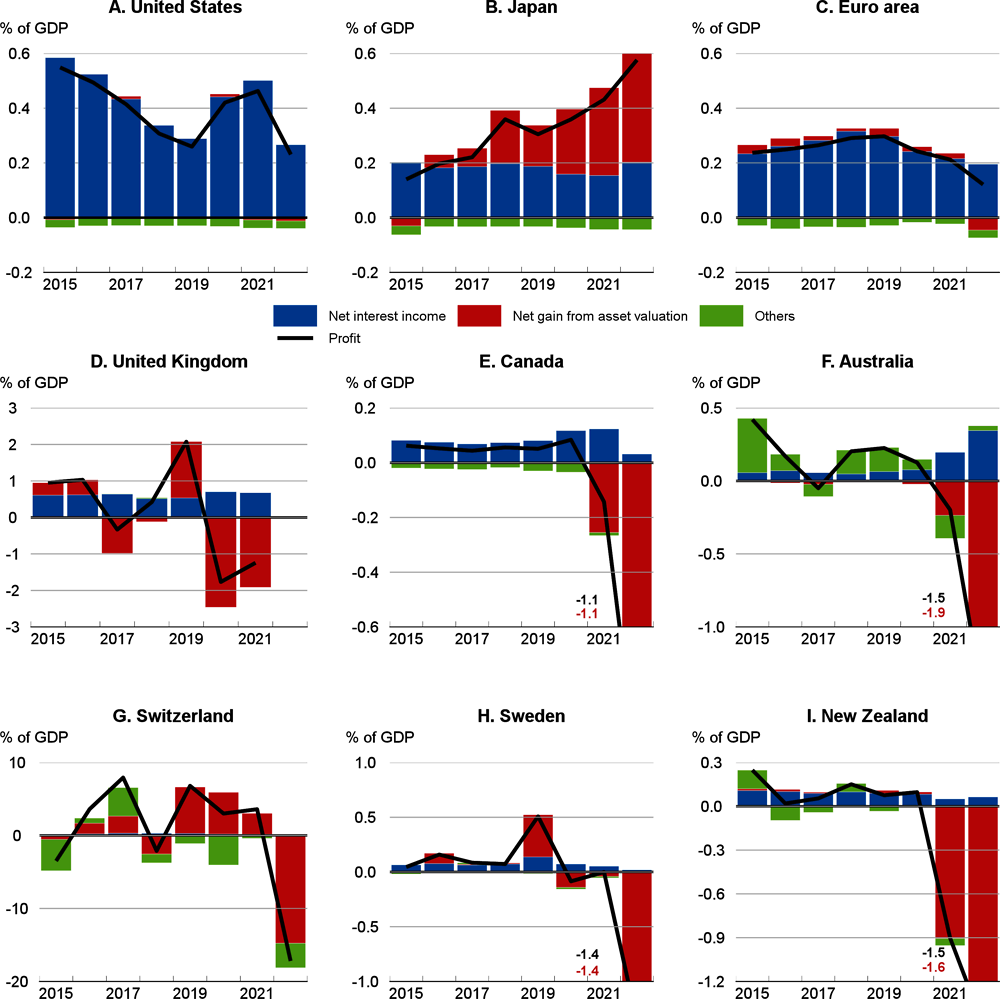

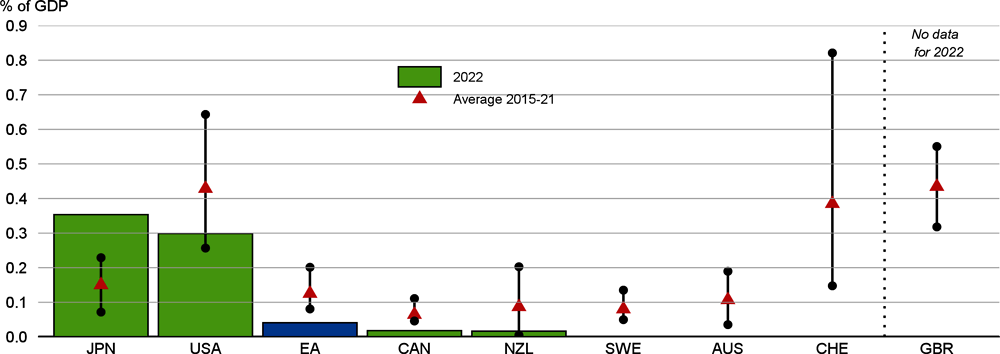

← 4. Income earned by banks on their activity of maturity transformation increased in 2022, enabling banks to rebuild profit margins after the pandemic. In contrast, data point to a renewed decline in bank profitability across a number of countries at the start of 2023.

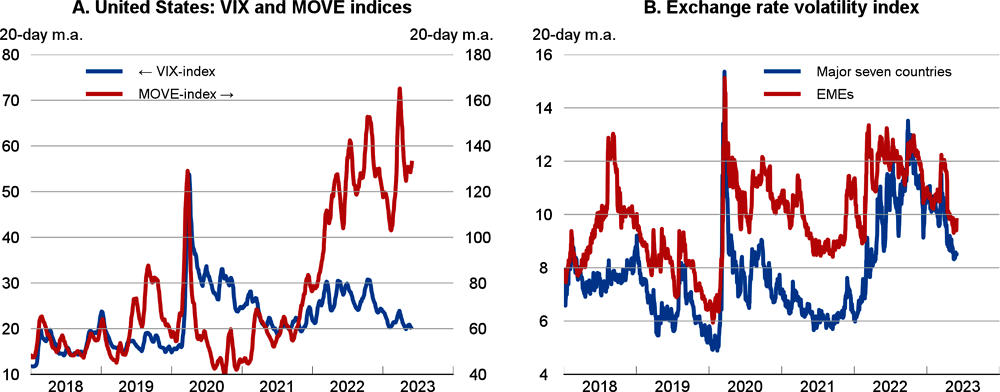

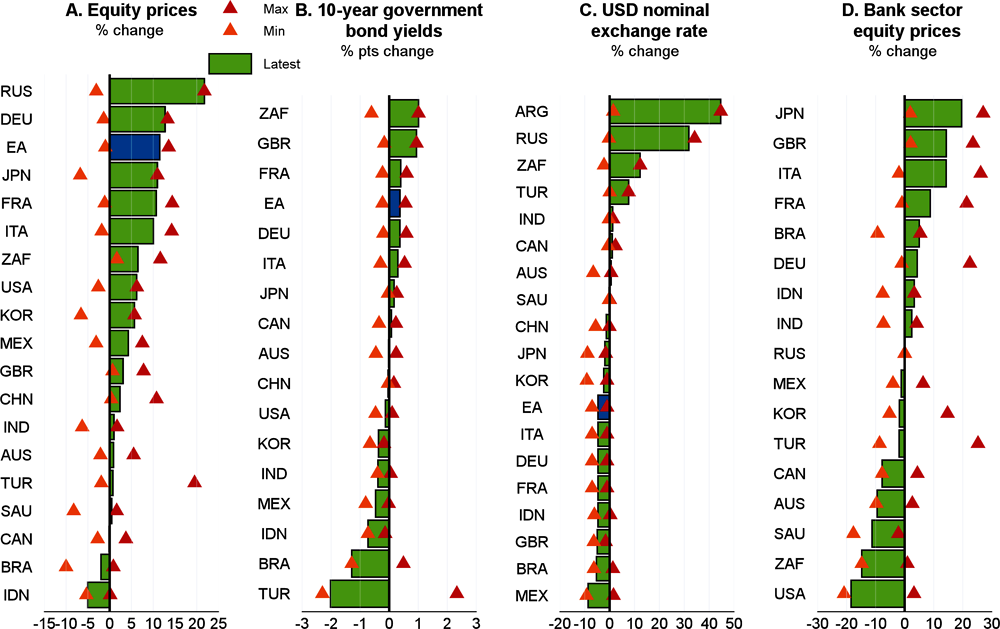

Wider market conditions have been volatile, but the prices of risky assets have regained momentum in recent months. Rapid changes in market expectations about the future path of monetary policy have generated continued volatility in government bond markets (Figure 1.9, Panel A), surpassing the peak observed at the height of the pandemic. Foreign exchange market volatility has declined from its March 2023 peak, but remains elevated (Figure 1.9, Panel B). Aggregate equity price indices have risen in most countries since late 2022, and bank equity prices have recovered in most advanced economies from low levels in March. Ten-year government bond rates have edged down in the United States but have risen in the euro area and in the United Kingdom (Figure 1.10), and term spreads in sovereign bond markets have generally widened. Real long-term rates on government bonds remain lower than typically observed prior to the global financial crisis. Sovereign spreads also remain contained across the euro area, helped by the availability of the ECB’s Transmission Protection Instrument and flexibility across countries in Eurosystem bond reinvestments. However, corporate bond spreads have widened, especially on corporate bonds in the advanced economies that are below investment grade.

The US dollar has depreciated against most advanced and emerging-market currencies since November 2022 (Figure 1.10, Panel C), helped by narrowing policy interest differentials between the United States and other countries and market views that US policy rates might be close to a peak. This has helped to limit signs of financial stress in emerging-market economies. Equity price indices have risen a little in China, reflecting the reopening of the economy, but fallen in some energy exporters amid lower commodity prices (Figure 1.10, Panel A). Yields on local-currency government bonds have generally declined in major emerging-market economies (Figure 1.10, Panel B), but spreads over US government bonds remain elevated in countries characterised by high inflation or risk premia. Foreign-currency government bond spreads over US government bonds have also declined in most emerging-market economies, suggesting sovereign credit risk so far remains contained. Investment-grade corporate bond yields in emerging-market economies are still below their peak in 2022, but above their average for that year.

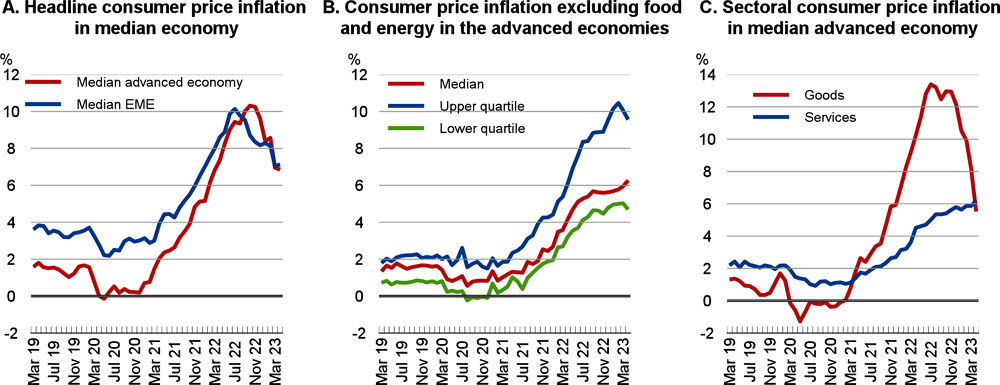

Underlying inflationary pressures remain high

Headline inflation has fallen in most economies in recent months due to the downturn in energy prices, even though food product and services prices have continued to rise rapidly. However, core inflation – excluding food and energy – remains stubbornly high in many countries (Figure 1.11). Core inflation is dominated by services, and services price inflation tends to be less variable than goods price inflation and more dependent on labour costs. Some services prices are also adjusted infrequently. For example, the rental component of consumer prices (including the imputed rents of owner-occupiers in some countries) generally lags the movements in market rents (new rentals), as prices for existing rents are only changed gradually, often once a year.2 Rising services price inflation also reflects the ongoing normalisation of demand patterns after the sharp shifts seen in the first year of the pandemic. Demand for services has rebounded, converging towards the pre-pandemic path in many countries, while the earlier surge in goods demand, particularly for durable goods, has ebbed.

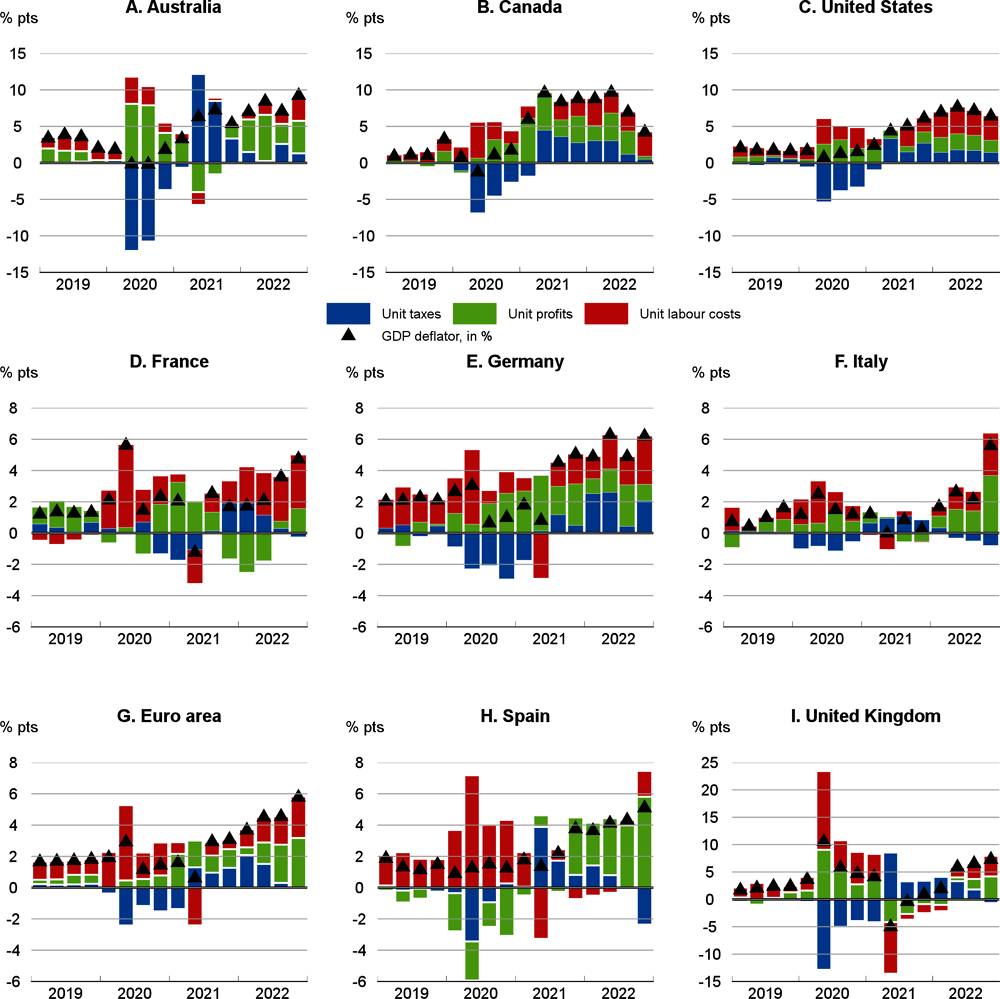

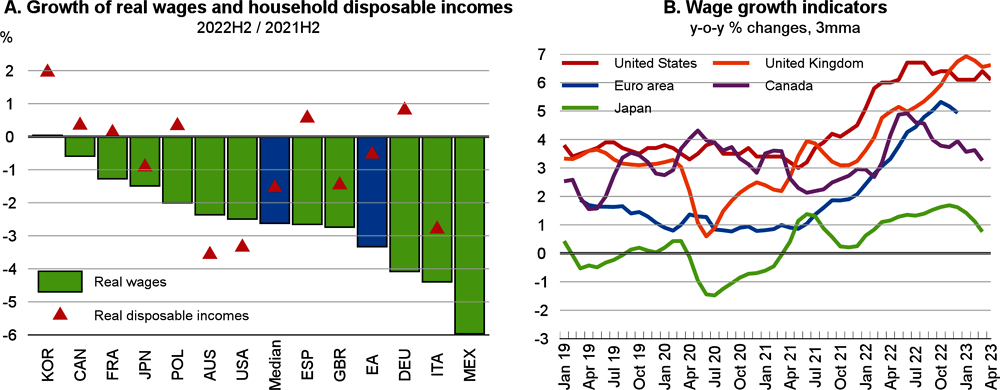

The upsurge in inflation in 2021-22 has led to declines in real wages and, in many countries, household disposable incomes (Figure 1.15, Panel A). However, continued employment growth and fiscal policy support have helped to limit the overall drop in household disposable incomes in some countries, especially in Europe.3 The weakness of household incomes, and the associated pressures on household purchasing power, have prompted concerns that the high rates of inflation seen in the past year have been due in part to firms raising their profits rather than simply passing on higher input costs. A decomposition of the factors contributing to the rate of growth of the GDP deflator – an indicator of domestically-generated price pressures – suggests that increases in both unit profits and unit labour costs help to account for the upturn in inflation, albeit to a different extent across countries (Box 1.2). A significant part of the unit profits contribution has stemmed from profits in the energy and agriculture sectors, well above their share of the overall economy, but there have also been increases in profit contributions in manufacturing and services.

Despite the slowdown in output growth, labour markets generally remain tight across most OECD economies, with OECD-wide employment and labour participation rates reaching historic highs in the fourth quarter of 2022 and the OECD unemployment rate remaining at a low of 4.8% in March this year. Labour supply shortages, which point to a need for additional well-targeted reforms in some countries, and real wage declines have generated a pick-up in nominal wage agreements, though the pace has remained relatively moderate. Some signs of easing labour market pressures are now emerging in many advanced economies. The number of vacancies has started to decline from elevated levels, layoff rates are increasing, employment of temporary help services has declined, and nominal wage increases have generally levelled off and in some countries even begun to decline (Figure 1.15, Panel B).

The price of every good or service can be broken down into the unit cost of inputs bought from other firms and value added per unit, with the latter in turn being decomposable into profits per unit, unit labour costs, and unit taxes (net of subsidies). With the upsurge in inflation in 2021-22 creating a cost-of-living crisis in many countries, there has been much interest in whether this is mainly attributable to firms securing higher unit profits, to higher wages (pushing up unit labour costs), or to some combination of the two. This Box explores the contributions from these different components to domestically generated inflation, and also compares recent experience with that seen in the 1970s, an earlier period of high inflation.

The data needed to estimate the impact of changes in unit profits, unit labour costs and unit taxes on consumer prices are not generally available directly. However, this breakdown can be calculated for the GDP deflator using the income measure of GDP (Arce et al., 2023; European Commission, 2023). The change in the GDP deflator (GDP inflation) differs from consumer price inflation, as the composition of household consumption is different from the composition of domestic output. Notably, many OECD economies are net importers of fossil fuels and food, and energy and food prices increased dramatically in 2021-22. Thus, for these countries, consumer prices increased by much more than the GDP deflator over that period. Conversely, for oil and gas exporters, the prices of goods produced domestically and then exported rose rapidly, pushing GDP inflation above headline consumer price inflation.

A decomposition of GDP inflation thus gives only a partial picture of the aggregate contribution of profits and labour costs to headline consumer price inflation.1 Nevertheless, since the GDP deflator measures the price of domestic value added, GDP inflation is an indicator of domestically generated inflation, and can shed light on the extent to which headline inflation is domestically generated or imported.

Conducting this decomposition for a range of OECD economies yields a number of insights:

The recent period is characterised by more frequent simultaneous increases in the contributions to inflation from unit profits and unit labour costs, a phenomenon last seen in the 1970s.

A large part of the higher unit profits contribution originates from mining and utilities, even in commodity-importing economies.

The recent period – so far at least – is unlike the 1970s in that GDP inflation was generally much higher in the 1970s, notably on account of stronger increases in unit labour costs.

The decomposition of GDP inflation since 2019 for three commodity-exporting OECD economies (Australia, Canada and the United States) and six commodity importers is shown in Figure 1.12. As expected, the commodity exporters experienced higher GDP inflation over 2021-22 than the commodity importers.

The contribution from unit profits was relatively stable in the last four quarters for the United States as well as for Germany, following several quarters of significant positive contributions.

In contrast, the contribution from unit profits has recently increased in many other European countries, including the aggregate euro area, France, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom.

The contribution from unit labour costs has recently risen in Australia, the euro area (including France, Germany and Italy), the United Kingdom and the United States.

While it is usually stable and small, the contribution from unit taxes was particularly volatile following the COVID-19 shock, reflecting pandemic-related subsidies that have subsequently been phased out and changes in the composition of expenditure, particularly household consumption.

Despite recent increases, the GDP inflation rate remains significantly below the levels seen in the 1970s, especially for commodity importers. In the oil crises of the 1970s, both unit labour costs and unit profits boosted GDP inflation to double-digit rates.2 In the current inflationary episode, the contribution of unit labour costs and, to a lesser extent, unit profits have been much smaller, especially for commodity importers.

The combination of rising unit labour costs and rising unit profits seen in 2021-22 for many countries, including Australia, Canada, the euro area (including Germany and Italy), the United Kingdom and the United States, is relatively unusual. Over the two decades prior to the pandemic, there was usually a negative correlation between unit profits and unit labour costs, with increases in one being partially absorbed by falls in the other. This relationship has weakened of late, with the median correlation amongst 17 OECD countries shrinking from -0.6 over 2000-19 (using quarterly data) to -0.2 over 2021-22, similar to the value for the decade 1971-81, another period characterised by large energy and food price shocks. This suggests that a period of rising input cost inflation may be conducive to unit profits and unit labour costs rising together, at least in nominal terms.

A key policy issue is whether the observed aggregate increase in unit profits reflects a generalised lack of competitive pressures throughout the economy, or specific factors that have contributed to strong profit growth in a few sectors or in a subset of firms. Moreover, an increase in unit profits (profits per unit of value added) does not necessarily entail higher profit margins (profits as a proportion of sales) as the increase of input costs (including intermediate consumption) can result in profits per unit of value-added moving differently to profits on gross output (or sales) (Colonna et al., 2023).

Evidence on the recent evolution of profit margins is mixed. Colonna et al. (2023) find that margins have risen in the United States and in non-tradeable sectors in Germany, and returned to pre-pandemic levels in Italy after an earlier decline. Weber and Wasner (2023), using firm-level data in the United States, argue that rising prices after COVID-19 were mainly the result of market power and implicit agreements between large firms. In contrast, Glover et al. (2023), suggest that the rise of mark-ups during 2021-22 was due to firms anticipating future cost increases rather than an increase in monopoly power or higher demand. A recent review of competition policy and inflation suggests that weaker competition may have contributed to the observed rise in cost pass-through and corporate profits (OECD, 2022c).

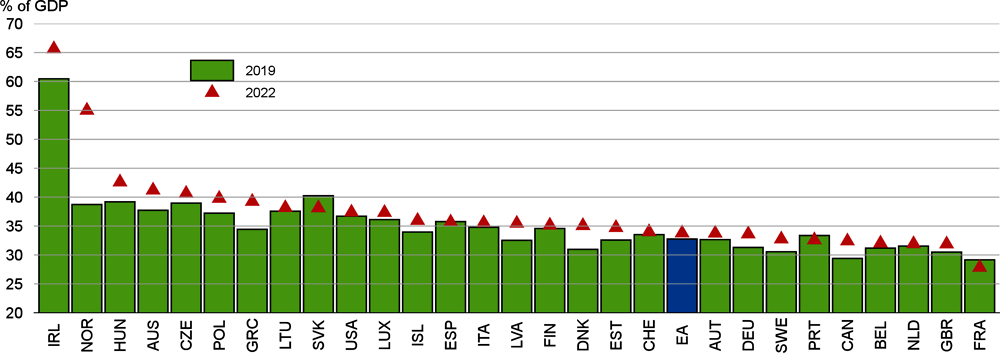

Indirect evidence that aggregate profitability has risen is provided by the evolution of the share of profits in GDP. In most advanced economies, the ratio of the gross operating surplus to GDP in 2022 was higher than in 2019 (Figure 1.13), implying that unit profits have risen faster than GDP inflation over this period.

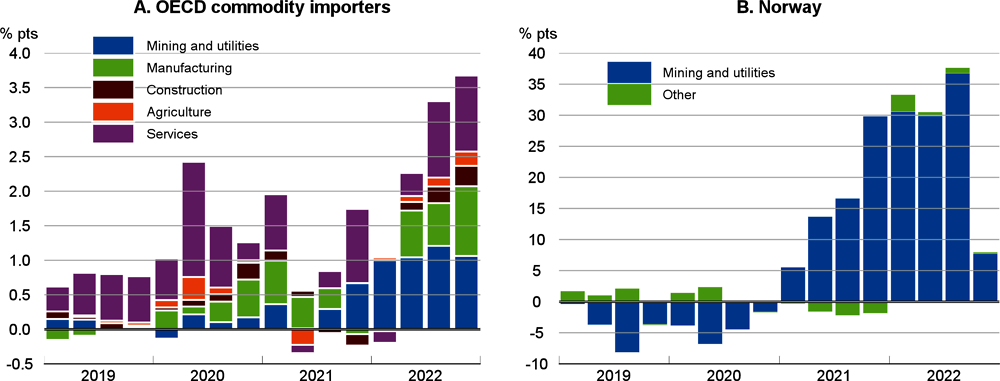

One indication of the extent to which rising aggregate unit profits reflects a broad-based increase in pricing power across sectors is to decompose the change in unit profits by sector. Doing this for the 13 OECD commodity-importing economies with an available sectoral breakdown of GDP, and computing unit profit as value added minus labour compensation and taxes, suggests that a disproportionate part of the observed increase of unit profits in 2022 came from mining and utilities: that is, mining and quarrying together with electricity, gas and water supply (Figure 1.14, Panel A). This sector accounts for only about 4% of the average economy but more than 40% of the rise of unit profits in 2022 as a whole. For commodity-importing countries this likely corresponds mainly to electricity and gas supply, including renewable electricity producers, who did not suffer from higher costs but benefited from higher retail prices. On a quarterly basis, the contribution of other sectors to the rise of unit profits gradually increased through 2022, with stronger effects from both manufacturing and services. The relatively small share of agriculture in the economy (less than 2% for the euro area) also masks a relatively large increase of the contribution of unit profits in this sector.

Due to an absence of compensation data by sector for most OECD commodity exporters, only Norway can shed some light on sectoral developments of unit profits for this group of countries. As expected, the bulk of the large increase in unit profits in Norway in 2022 came from mining and utilities (Figure 1.14, Panel B), with the contribution of unit profits to GDP inflation plummeting in 2022Q4 because of the global fall in energy prices. It is likely that mining similarly accounts for a large share of the rise in unit profits during 2021-22 in other commodity exporters such as Australia and Canada.

← 1. Diev et al. (2019) use an alternative approach that decomposes core CPI inflation instead of GDP inflation with some additional contributors to inflation (including the terms of trade excluding food and energy) but using the same definition of unit profits and unit labour costs. Haskel (2023) proposes a similar decomposition of headline CPI inflation.

← 2. There are a few countries in which the GDP deflator growth rate is relatively similar to the 1970s: for example, the average annual growth rate over 1971-81 in Germany was 5%, slightly below the value for 2022 (5.5%).

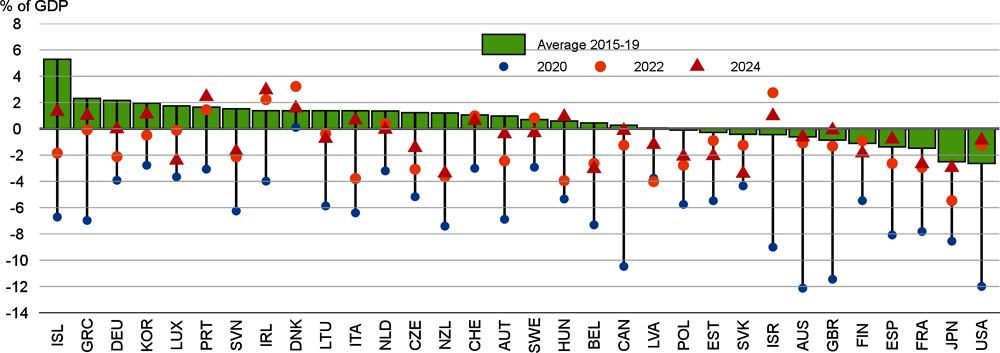

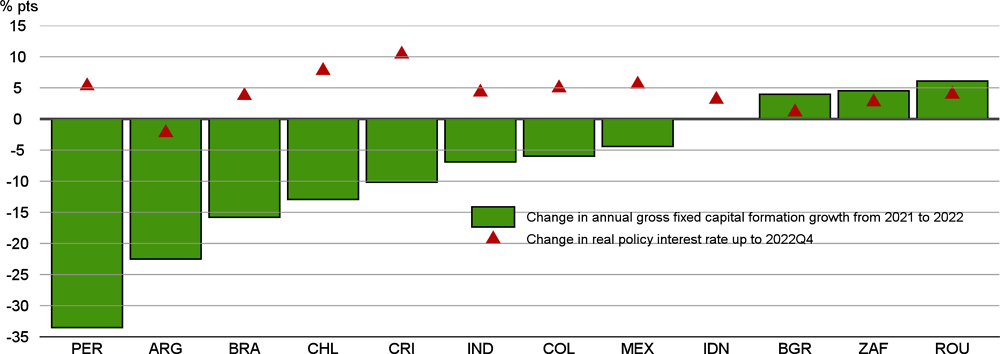

Despite the signs of improvement seen in the early months of this year, the outlook is for a period of subdued growth and persisting inflation amidst acute risks. The full effects on output from the quick and synchronised tightening of monetary policy since the start of 2022 are likely to appear over the course of 2023 and early 2024, particularly on private investment. Central banks, faced with persistent above-target inflation, are expected to keep interest rates high, and most countries are set to adopt a tighter fiscal stance to start alleviating debt burdens worsened by the pandemic. However, stronger public investment, supported by NGEU grants, could provide some support to activity in many European countries. Household incomes remain under pressure, with lower energy and food commodity prices yet to be fully reflected in retail prices, although use of additional savings accumulated during the pandemic could help to cushion demand. The disruption from the war in Ukraine is also likely to continue to weigh on the global economy.

Global GDP growth in 2023 is projected to be 2.7% (Figure 1.16, Panel A), the lowest annual rate since the global financial crisis, with the exception of the pandemic-hit year of 2020. A modest improvement to 2.9% is foreseen for 2024, but this would still be a relatively poor outcome by historical standards. The slowdown in annual growth from 2022 masks a gradual improvement in the year-on-year growth of global activity over the course of 2023. This improvement partly reflects the fall in energy prices, but mainly stems from the emerging-market economies and the positive impetus provided by the rebound in China after fully reopening its economy. In addition, a disproportionate share of global growth in 2023-24 is expected to continue to come from Asia (Figure 1.16, Panel B). If the economic impact of China’s reopening is less than expected, a main pillar of global growth this year and next would be weakened.

Annual OECD GDP growth is projected to be below trend at 1.4% in both 2023 and 2024, although it will gradually pick up on a quarterly basis through 2024 as inflation moderates and real income growth strengthens. Business investment is projected to be nearly stagnant in the OECD area in 2023, and housing investment is projected to decline in many economies. Overall GDP growth is sustained by steady increases in private consumption and government final expenditure, the former being supported by continued, albeit modest declines in saving ratios on average across the OECD this year. Real wages, which fell in all major OECD economies in 2022, are projected to stop declining over the course of 2023 in most, and OECD-wide employment is projected to keep expanding in 2023-24, underpinning incomes. Any negative shocks to household sentiment or wealth, or a less benign evolution of the labour market, would yield weaker growth in consumption and output.

The prospects for individual major economies and regions are as follows.

In North America, the sharp rise in interest rates since late 2021 has been reflected in a slowdown in final domestic demand growth in both the United States and Canada. Housing investment has declined sharply, and business investment is showing signs of weakness. Lower saving rates and robust increases in employment are helping to maintain private consumption growth, but this is set to fade. Annual GDP growth in the United States is projected to be 1.6% this year, helped by strong carryover effects from late 2022, and 1.0% in 2024. Annual growth in Canada is projected to be 1.4% in both 2023 and 2024, supported by strong population growth and a resilient labour market. In both economies, the average annual growth numbers obscure a projected improvement in quarterly growth rates through the course of next year, helped by the moderation of inflation towards 2% by the end of 2024.

Although inflation has increased in the major advanced Asian economies, it remains relatively mild. The reopening of China should also provide a boost to demand in the wider region. In Japan, monetary policy remains accommodative, and fiscal policy is set to be largely neutral this year before becoming less supportive in 2024. Policy support, together with signs of stronger wage growth, is projected to help GDP growth pick up to an above-trend pace of 1.3% in 2023 and 1.1% in 2024 and bring underlying inflation up towards 2% by the latter half of 2024. In contrast, macroeconomic policy is already tightening in Korea, and domestic demand growth is expected to remain relatively subdued amidst high debt service burdens. GDP growth is projected to be 1.5% in 2023 and 2.1% in 2024, with exports set to pick up with China’s recovery and an upturn in the tech cycle.

- Las principales economías europeas se han visto fuertemente afectadas por la guerra en Ucrania, a través de los elevados precios de la energía y el aumento de la incertidumbre. Las políticas macroeconómicas se están volviendo menos favorables, con tipos de interés oficiales más altos y una consolidación fiscal en curso. En la zona del euro, se prevé que el crecimiento del PIB sea del 0,9% en 2023. La rigidez de los mercados laborales, junto con nuevos descensos de las tasas de ahorro de los hogares, deberían respaldar el consumo privado, pero el aumento de los costes de financiación y el endurecimiento de las normas crediticias pesarán sobre la inversión, a pesar del impulso del mayor gasto en el marco del programa NGEU. Se espera que el crecimiento del PIB aumente hasta el 1,5% en 2024, favorecido por el aumento de los ingresos reales a medida que disminuye la inflación. La inflación general de la zona del euro caerá con bastante rapidez a medida que la inflación de los alimentos y la energía se vuelva negativa en términos interanuales, pero se prevé que la inflación subyacente se mantenga estable, próxima al 3% interanual en el último trimestre de 2024. Se prevé que la elevada dispersión actual de la inflación entre los países de la zona del euro se modere sólo gradualmente. El patrón de crecimiento e inflación durante 2023-24 es muy similar para el Reino Unido, pero la política fiscal es más restrictiva en ambos años y se espera que el crecimiento de las exportaciones siga siendo muy débil. Se prevé que el crecimiento del PIB sea del 0,3% en 2023 y aumente hasta el 1% en 2024, a medida que empiece a mejorar el crecimiento de la renta real. Se prevé que la inflación general y la subyacente anuales disminuyan, pero sigan estando ligeramente por encima del objetivo a finales de 2024.

China is expected to see the sharpest positive shift in growth between 2022 and 2023 of any G20 economy, largely on account of the lifting of the government’s zero-COVID policy. GDP growth is projected to rise to 5.4% in 2023, and then ease to 5.1% in 2024 as the rebound associated with reopening fades. The shift in the anti-COVID policy has released pent-up demand for in-person services, lifted consumer confidence and alleviated the downturn in the property sector. China is unusual in having experienced little inflationary pressure during 2022, and consumer price inflation is projected to remain benign.

Over the past year, GDP growth has remained relatively strong, and close to potential, in India and Indonesia, but monetary policy has been tightened to lower inflation and fiscal policy is becoming less supportive. GDP growth in India is projected to ease to 6% in FY 2023-24, as tighter financial conditions hold back domestic demand, before picking up to 7% in FY 2024-25, helped by lower inflation and stronger external demand. Indonesia’s average annual growth is projected to remain close to 5% over 2023-24, underpinned by solid business and consumer confidence, and stronger international tourism from China.

After a strong rebound last year, growth will slow sharply in most Latin American economies in 2023, reflecting generally tight macroeconomic policies to tackle persistently high inflation, soft growth in export markets and lower prices for key export commodities. Output growth is projected to pick up in 2024 as inflation subsides, monetary policy becomes less restrictive and external demand strengthens. After the large boost from agricultural output in the first quarter of 2023, GDP growth in Brazil is projected to moderate, with annual growth of 1.7% in 2023 and 1.2% in 2024, as high real interest rates and weak credit growth hold back domestic demand, despite stronger social transfers.

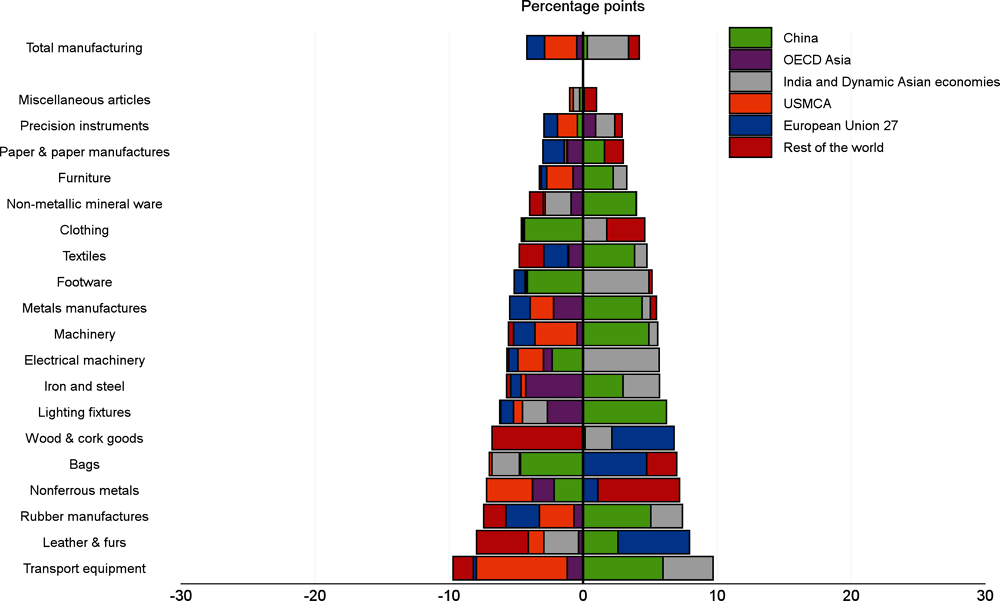

Global trade growth is projected to slow alongside GDP growth in 2023 to 1.6%, in part due to carryover effects from the weakness in late 2022, before recovering to 3.8% in 2024. Lower commodity prices and the full reopening of China should help to support trade growth over next eighteen months, including in Europe (Figure 1.17, Panel A), although base effects will keep annual growth very low in 2023. The lagged effects of tight monetary policy will continue to be felt into 2024, particularly in the United States. The trade intensity of growth is set to decline in 2023, before recovering in 2024, as rising trade in OECD countries offsets the continued weakness in Chinese trade intensity (Figure 1.17, Panel B). Growth in the trade of services is expected to outperform goods, with the re-opening of the Chinese economy providing a substantial boost to international travel particularly in 2024.

The recovery in trade could be weaker if growth disappoints or possible second-round impacts from trade-related sanctions on Russia limit the pace of the trade rebound. However, if domestic demand picks up faster than expected, trade could recover faster, as supply chain pressures in manufacturing and shipping have mostly abated and estimates of spare capacity are high across most manufacturers. A faster-than-projected normalisation in China’s tourism market could also result in higher trade growth. Services import volumes in China in 2022 were still 26% lower than 2019 levels. International tourism estimates are still 20% below 2019 peaks, suggesting room for a full recovery if growth should surprise to the upside in 2023. If global travel services grew sufficiently to return to their share of global trade in 2019 (5.7%), it would boost the value of total trade by just over 1½ per cent in 2023.

A key question for the outlook is the extent to which the slowdown in output growth will push up unemployment rates. So far, despite many advanced economies having already had at least one quarter of negative GDP growth, unemployment has remained low and even continued to fall in some countries. Instead, two margins of adjustment to a weaker demand environment have been the number of job vacancies, which is now declining in many OECD economies, and hours worked, which have begun to move down in some countries. With the projected slowdown in demand growth expected to be relatively mild, unemployment is projected to rise only marginally during 2023-24, especially in the euro area. The OECD-wide unemployment rate is expected to increase from 4.9% at the end of 2022 to 5.2% in the fourth quarter of 2024, though with relatively large rises of around ¾ percentage point or more in Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States. With labour markets generally expected to remain tight, and with workers having experienced falls in real wages in 2022, nominal wage growth is projected to be just over 4% in the overall OECD area in 2023, before moderating to around 3½ per cent in 2024.

Helped by the decline in energy prices over the past few months, average annual headline inflation in the OECD as a whole is now projected to fall relatively quickly from 9.4% in 2022 to 6.6% in 2023 and 4.3% in 2024, with year-on-year inflation in the last quarter of 2024 down to 3.8% (Figure 1.18).4 In the major advanced economies, annual inflation is projected to be closer to target, at just over 2¼ per cent by the fourth quarter of 2024. The projected fall in OECD core inflation is shallower, reflecting the stickiness of many prices and a slow adjustment of margins and cost pressures. Core inflation is projected to ease from 6.6% in 2022 to 6.5% in 2023 and 4.5% in 2024 on an annual average basis.

Inflation could be more persistent than expected, with interest rates being higher for longer

Over the past eighteen months or so, underlying inflation has consistently proved to be higher than projected. The large shocks that have affected the global economy and the range of factors contributing to higher inflation, both on the demand and the supply side, have made it difficult to assess the speed at which inflation pressures may recede. Relatedly, after an extended period of low interest rates, there is considerable uncertainty concerning the impact of the monetary tightening that has already occurred. If the rise in interest rates has smaller-than-expected and/or delayed effects, or cost pressures moderate less rapidly than expected, or firms try to raise price-cost markups, inflation will be higher than projected. In such circumstances, monetary policy will have to be tightened further and perhaps kept restrictive for longer, with negative implications for growth and employment and greater risks for financial stability.

The extended period of high inflation has already resulted in a rising share of items in consumer price baskets that have had annual price rises of more than 5% for at least 12 months. This share has gone from near zero at the beginning of 2021 to around a quarter on average by April 2023, and to a third or more in Germany and the United Kingdom (Figure 1.19). Delays in getting inflation down would be likely to raise these shares further, intensifying the challenges of lowering inflation, increasing the risks of market and private sector inflation expectations settling at levels well above inflation objectives, and possibly also prompting a drift towards greater indexation of contracts and financial assets. In these cases, inflation would likely prove more persistent than projected.

Other factors might also contribute to inflation persistence. Notably, an aggravation or spreading of the conflict in Ukraine could yet give new upward impetus to energy and food prices. Likewise, a stronger-than-expected rebound of the global economy this year could push up a range of commodity prices and hinder the downward move in inflation. Again, policy rates would be likely to be kept higher for longer than projected, with a higher probability of a widespread and harmful economic slowdown and enhanced risks of financial stress.

Tighter financial conditions could trigger stress in financial markets

Tighter financial conditions are to be expected as monetary policy becomes more restrictive, and are a standard channel through which policy affects output and inflation. Nonetheless, there are risks that an abrupt tightening of financing conditions could trigger widespread financial stress and undermine stability as investors rapidly reassess exposures to liquidity, duration and credit risks. Key concerns are that renewed fragilities could appear in the banking sector, resulting in a broader loss of confidence and a sharp contraction of credit, and a heightening of risks from liquidity mismatch and leverage in non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs).

Collectively, the banking system appears more resilient than before the global financial crisis, with post-crisis regulatory reforms strengthening capital and liquidity positions, and the largest banks being subject to more stringent stress tests. Large systemically important banks in advanced economies appear to be liquid and adequately capitalised, although market confidence remains fragile, as shown by the speed at which banking sector pressures spread across countries following bank failures in the United States in March. Moreover, capital ratios stand above regulatory minima, non-performing loans (NPLs) remain low, and recent stress tests suggest that large banks are generally well positioned to cope with fast rising interest rates and a flattening of yield curves (IMF, 2022a; ECB, 2022).

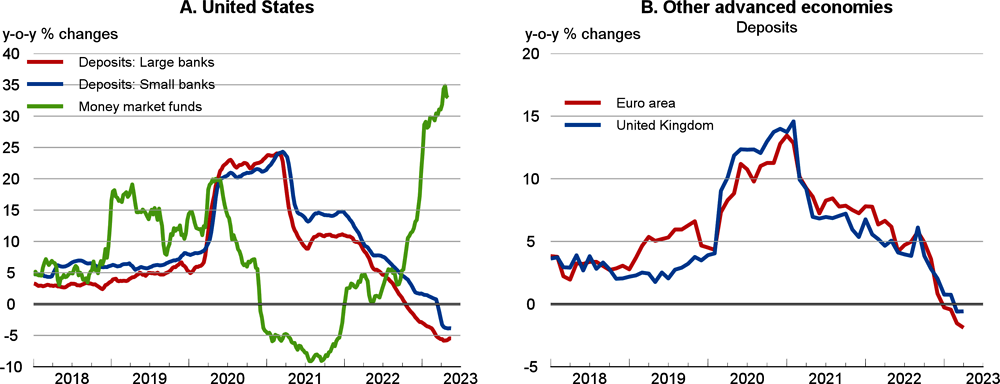

Nonetheless, recent episodes in the United States and Europe suggest that in an environment of fast-rising interest rates, banks can be exposed to severe duration and liquidity risks if large deposit outflows occur. Deposit growth has slowed in the large advanced economies since early 2021 and in many has recently become negative (Figure 1.20). With bond yields rising fast, savers can get higher returns by moving deposits away from banks and towards money market funds (MMFs), as seen in past episodes of policy tightening (Paul, 2022).

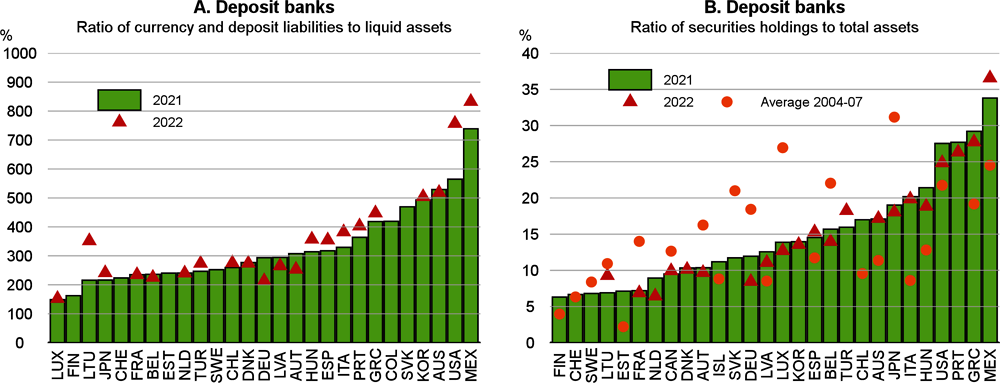

Duration risks can arise if the value of fixed-income securities falls as a result of higher interest rates. While losses may only be realised over time, they can materialise rapidly if banks have to sell bonds to meet unexpected deposit outflows. In addition, liquidity risks can become manifest for banks with low liquid assets and large short-term liabilities. While liquidity mismatches vary widely across countries, banks in Mexico and the United States tend to have comparatively high ratios of short-term liabilities to liquid assets and therefore might be more vulnerable to liquidity risks triggered by large deposit outflows (Figure 1.21, Panel A). Banks in Mexico, the United States and some European countries could also be potentially vulnerable to duration risks, given their comparatively high, albeit often declining, share of government bonds in total assets (Figure 1.21, Panel B). The prospect of large losses by banks and poor liquidity conditions can lead to a sharp repricing of bank risk and higher bank funding costs, pushing banks to tighten lending conditions to households and companies.

Banks could also face pressures from rising credit losses if firms and households struggle to repay their debts, which in turn would significantly reduce the supply of new credit available for households and companies. In a number of countries, private sector debt-service ratios in 2022 were already above those in the early 2000s, when interest rates last rose sharply (OECD, 2022b). The share of borrowers unable to service debt payments could increase as rising policy rates are passed through to lending conditions, particularly in countries in which private debt levels are elevated and in which a sizeable share of debt is at variable interest rates.

A sharp correction in house prices or commercial real estate (CRE) prices could also exacerbate household and corporate solvency risks, leading to large potential losses for banks. CRE transaction activity has declined globally (IMF, 2023), and CRE prices have started to decline in the major advanced economies. By the fourth quarter of 2022, CRE prices were 1.8% and 2.9% below their most recent peaks in the United States and the euro area respectively, and monthly indicators based on Real Estate Investment Fund valuations point to further sharp declines in values this year. In the event of severe stress in property markets, banks could be forced to realise losses on loan portfolios if there were fire sales or foreclosures on a large scale, reducing the value of available collateral. A sharp repricing of CRE could weigh heavily on US regional bank balance sheets, as they account for a sizeable share of lending to the sector (FDIC, 2022). In addition, there have already been some signs of asset quality deterioration, amid rising bankruptcies and delinquency rates for mortgage loans in several countries (FOMC, 2023; Eurostat, 2023; Sverige Riksbank, 2022), which may require higher loss provisions and force banks to take steps to replenish their capital positions.

There are also broader indications that corporate bankruptcies have begun to increase in many countries, including in Europe, after a long period when they were at unusually low levels helped by pandemic-related support from governments. While a higher level of business failures is not surprising given the higher energy costs and debt servicing costs that firms face, a sharp acceleration could also place an additional source of stress on the balance sheets of lenders, including NBFIs.

Non-bank financial institutions now account for around 50% of global financial assets (FSB, 2022a), a significantly larger share than before the global financial crisis. Credit to firms by NBFIs in 2022 accounted for 20% of total outstanding loans to non-financial corporations in the euro area and 50% in the United Kingdom (ESRB, 2022; IMF, 2022a). NBFIs’ provision of credit to households has also risen. For example, in 2021 more than 70% of mortgages were originated by NBFIs in the United States (Federal Reserve, 2022), NBFIs are particularly exposed to risks from liquidity mismatch and the use of derivatives and other forms of leverage to fund investments in illiquid assets (Bank for International Settlements, 2021). These institutions could come under stress in an environment of rising interest rates and declining asset prices if they are forced to realise large mark-to-market losses on their assets to try and meet sizeable margin calls on leveraged trades (due to the decline in collateral values). Such a scenario would be likely to further destabilise asset markets in the absence of prompt policy action. In addition, if NBFIs are forced to sell assets to accommodate outflows, a negative spiral could kick in, amplifying adverse market dynamics and generating a further tightening of financing conditions for non-financial corporations.

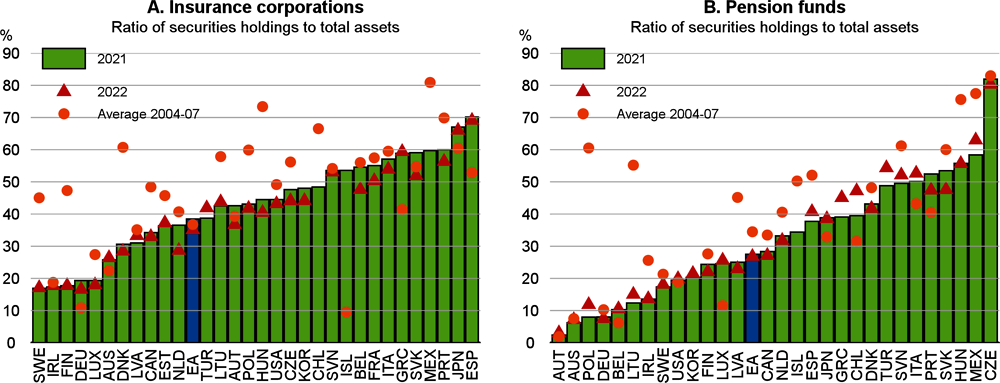

In many OECD countries, holdings of debt securities by MMFs and insurance companies stand at above 50% of total assets (Figure 1.22). Pension funds and financial companies engaged in securitisation could also be vulnerable given their use of leverage (ESRB, 2022). Further efforts are also needed to enhance the resilience of MMFs. Such funds could be vulnerable to large redemption calls and may face challenges in selling assets under stressed conditions (FSB, 2022b; Federal Reserve, 2023). Real estate investment funds could also incur severe losses if housing prices undergo sharp corrections (Daly et al., 2023).5

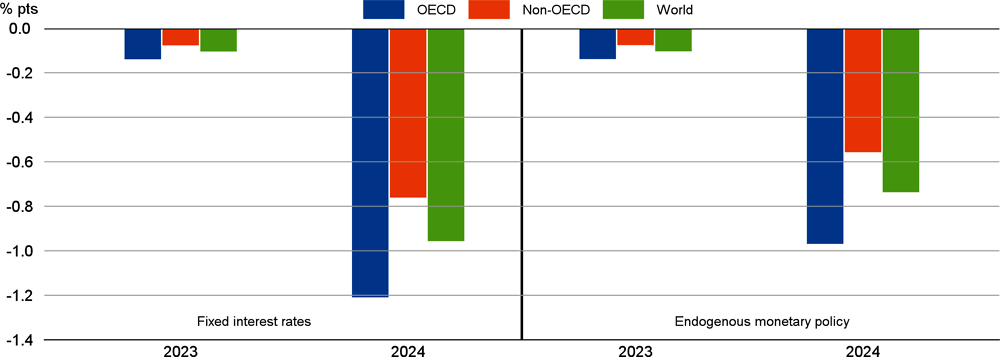

Illustrative scenarios, using the NiGEM global macroeconomic model, highlight the potential implications for growth if financial stress were to result in the cost of finance for households and firms rising by more than expected in the advanced economies. The scenarios consider three particular financial shocks, a rise of 1 percentage point in the wedge between household borrowing and lending rates, a rise of 1 percentage point in the user cost of capital due to higher funding costs, and a rise of 50 basis points in equity risk premia. These shocks are largely between one-quarter and one-half of the corresponding changes seen in past stress episodes, although this varies across countries. In contrast to the global financial crisis, the shocks are not assumed to spread directly into financial conditions in the emerging-market economies, and credit remains available to households and firms but at a higher price than before. The illustrative shocks are assumed to apply in the latter half of 2023 and in 2024 before fading, and are treated as unanticipated shocks for firms, households and financial markets.

In a scenario of this kind, for given policy settings, growth in the OECD economies could be lowered by around 1¼ percentage point in 2024, with global GDP growth reduced by almost 1 percentage point (Figure 1.23). This would push many advanced economies into or close to recession given the baseline projections for 2024. Higher financing costs would hit incomes, asset prices and domestic demand, with private sector investment declining by close to 7% relative to baseline in the advanced economies in 2024, equity prices dropping by close to 10% and unemployment rising by around ½ percentage point in the major economies. Inflationary pressures would also ease, by around 0.4 percentage points in the OECD economies in 2024. The emerging-market economies would be adversely affected due to weaker demand from the advanced economies, with growth in the non-OECD area declining by around 0.7 percentage points in 2024. If tighter financial conditions were to hit confidence, or generate significant stress in particular financial market segments, the adverse effects of the shocks would be stronger.

Macroeconomic policies can help to cushion part of these shocks. In particular, lower policy interest rates would mitigate the shocks, with the adverse impact on global GDP growth in 2024 reduced by around one-quarter. In the typical economy, policy interest rates are lowered by around 50 basis points in 2024, relative to baseline. An additional offset could be provided by fiscal policy if the automatic fiscal stabilisers were also allowed to operate fully in all countries, with budget deficit-to-GDP ratios rising relative to plans. Even in the absence of such a fiscal adjustment, the government debt-to-GDP ratio is around 2 percentage points higher by the end of 2024 in the median advanced economy (due to the lower level of GDP).

Tighter financial conditions could exacerbate vulnerabilities in emerging-market economies

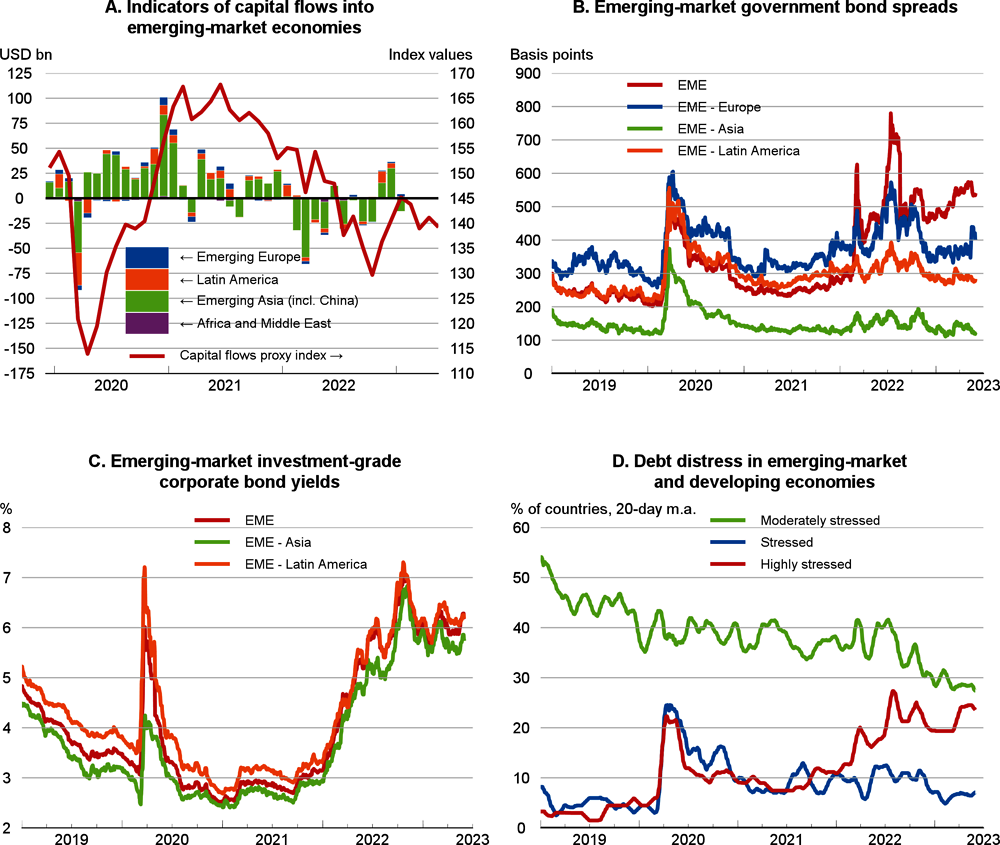

Since November 2022, financial market conditions in emerging-market economies have been broadly stable. The appreciation of the US dollar has come to a halt, the reopening of China has boosted the growth prospects of some commodity exporters, and the spillovers from the recent banking stress in major advanced economies have been limited, with sovereign and corporate bond yields changing only marginally. However, increased financial market volatility, higher external indebtedness and large bank exposures to domestic sovereign debt are aggravating vulnerabilities in emerging-market and developing economies. Several low-income countries have faced increasingly tight financing conditions, with a rising debt service burden due to higher sovereign spreads and greater reliance on USD-denominated debt. In the medium run, climate-related risks could also dampen growth prospects and increase inflationary pressures in emerging-market and developing economies.

Emerging-market and developing economy sovereign debt issuance declined by about 7% (USD 300 billion) in 2022 (OECD, 2023d). Corporate debt issuance has also declined (World Bank, 2023) and portfolio inflows have slowed, with higher yields available in the advanced economies (Figure 1.24, Panel A).6 Foreign-currency sovereign bond spreads and corporate bond yields have risen recently in all regions since early March, although they generally remain below the peaks seen in 2022 (Figure 1.24, Panels B and C). The pressures have been strongest in highly indebted low-income countries, many of whom are now in sovereign debt distress. About one-quarter of 62 emerging-market and developing economies now have a foreign-currency sovereign bond spread of more than 10 percentage points (Figure 1.24, Panel D) and more than 40% of sovereign debt is due within the next three years in low-income emerging-market and developing economies (OECD, 2023d).7

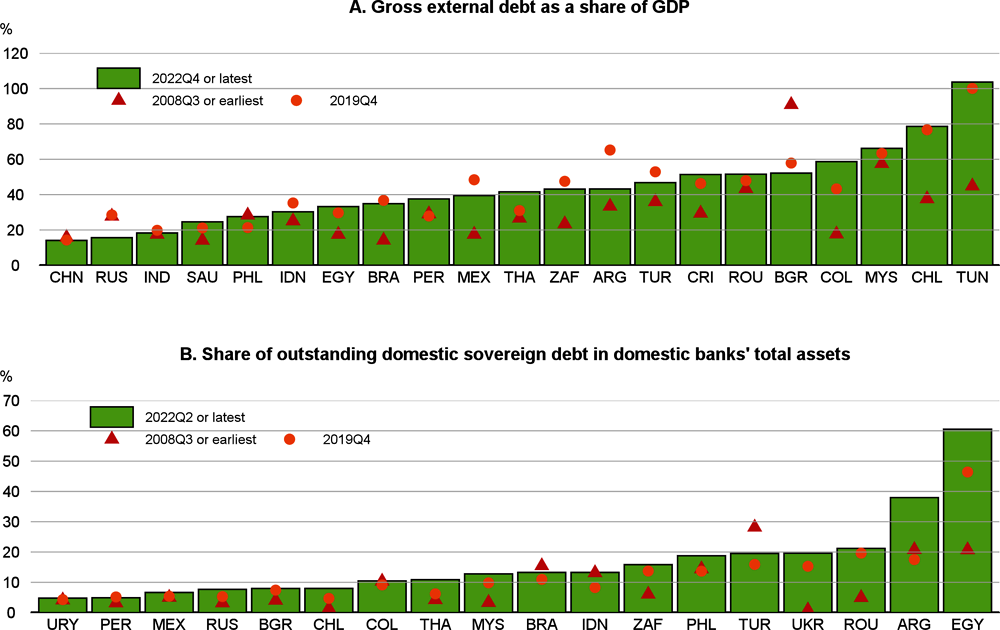

External debt and the exposure of domestic banking sectors to domestic government bonds have increased in emerging-market economies since the global financial crisis, although the nature of risks differs across economies.

Among the countries with high external debt (Figure 1.25, Panel A), Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Malaysia, South Africa and Türkiye had short-term financing needs – defined as the sum of short-term debt due on a residual maturity basis and the cumulative current account deficit 12 months ahead – of more than 15 percentage points of GDP in 2022 (IMF, 2022b). The current account deficit widened by 0.8 percentage points of GDP in 2022 in the median emerging-market economy, and by more in commodity importers, with most of this deterioration driven by a worsening of the trade balance.8

In addition, some countries with relatively high external debt, such as Costa Rica, Colombia, Malaysia and Romania, also experienced a sharp decline in their investment income balance. FDI inflows declined by 35% in the G20 emerging-market economies in 2022 (OECD, 2023c) although they have remained large enough to cover a sizeable portion of current account deficits in several Latin American countries, including Brazil, Colombia and Mexico. In other countries, there are risks of greater reliance on short-term external financing, potentially raising exposure to rollover risk.

In countries where the banking system exposure to the government is large, such as Argentina and Egypt (Figure 1.25, Panel B), a loss of confidence or higher perceived sovereign risk would raise risks of an adverse feedback loop between sovereign and bank balance sheets.9 This would also hinder private sector financing and growth, given that banks have been the main source of credit in emerging-market economies (Ehlers and Víllar, 2015).

In addition to potential financial tensions, emerging-market and developing economies continue to face medium-term climate-related risks, such as droughts, which could hurt growth prospects and reignite inflationary pressures (Kabundi et al., 2022). In particular, the higher share of food in consumption baskets (OECD, 2022a), continued pressures on food security, and lower resilience to extreme climate events in emerging-market and developing economies could lead to protracted inflationary effects (Faccia et al., 2021).

Risks from energy markets have not disappeared

In Europe, the risk of a critical shortage of energy supplies has diminished but not disappeared. Gas storage levels are near record levels for the time of year, contrary to earlier fears. Consumption has declined sharply in the face of record high prices, down by 17.7% in the EU in the eight months to March 2023, helped by warm weather during the Northern Hemisphere winter, investments in energy efficiency, and lower output from some energy-intensive industries. Liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports also remain at high levels, helped by new offshore storage capacity in some countries. There are also some residual imports by pipeline from Russia. Nonetheless, some challenges remain in securing sufficient storage levels for the 2023-24 winter. Supply from Russia in 2023 is likely to be minimal, in contrast to the early months of 2022, and a potential rebound in demand in China would increase competition for tight global LNG supply. This could push up energy prices once again, resulting in a renewed spike in consumer prices and further economic dislocation. Risks of higher prices also remain in oil markets, given continued uncertainty as to how output cuts by OPEC producers and Western sanctions on crude oil and oil products from Russia will affect global supply through the course of 2023.

Upside risks

While the balance of risks is skewed towards slower global growth and/or more persistent pressure on inflation, there is also a range of factors that could lead to more favourable macroeconomic outcomes.

The dynamics of growth, employment and inflation since 2020 have largely reflected forces associated with the pandemic, including the policy responses to it. The exceptional nature of that episode and the reopening of economies means that there is necessarily a great deal of uncertainty about how those dynamics will evolve. In particular, stronger labour force growth than projected would boost output and facilitate disinflation. After a virtual freezing of international migration during the first phase of the pandemic, migration flows to a number of advanced economies have been very large, in part reflecting a catch-up from the interruption in 2020-21. A continuation of similar net inflows would push labour force growth in these countries above what is projected. There are also a number of countries, including the United States and the United Kingdom, where there is scope for more people to enter the labour force as reductions in domestic labour supply resulting from the pandemic are unwound.

Another feature of pandemic-era labour markets in many economies has been the exceptionally high number of vacancies, often greatly exceeding the number of those looking for work. If labour demand can be cooled by a reduction in the excess of vacancies over jobseekers, with little if any increase in unemployment rates, then a given amount of disinflation can be achieved with more economic growth than otherwise. Relatedly, the ongoing unwinding of the shifts in the composition of demand associated with the pandemic (initially towards goods and subsequently towards services) could proceed more quickly and smoothly than expected, helping to moderate the currently persistent upward pressure on services price inflation.

Among emerging-market economies, one source of possible upside risks is that better financial conditions could support investment, including foreign direct investment (FDI), and private sector balance sheets. This would boost overall investment and growth prospects and help to reduce the vulnerability of countries to sudden stops or reversals of capital inflows.

In addition, there are a number of possible shocks that could be favourable for growth while worsening the inflation outlook or vice versa. For example, a faltering of China’s expected rebound this year, or stronger-than-expected effects from tighter monetary policy would likely help to bring down global inflationary pressures more quickly than projected, but would also weaken global growth. On the other side, if remaining pandemic-era excess savings are greater than estimated or if they are run down faster than projected, that would be positive for growth but would hinder the pace of disinflation.

La persistencia de las presiones inflacionistas, las modestas perspectivas de crecimiento y los importantes riesgos a la baja generan difíciles retos para los responsables políticos. Los tipos de interés elevados serán necesarios durante algún tiempo para garantizar una reducción duradera de las presiones inflacionistas. En caso de nuevas tensiones en los mercados financieros, los bancos centrales deberán hacer pleno uso de los instrumentos de política financiera disponibles para garantizar una liquidez adecuada y minimizar los riesgos de contagio. El descenso de los precios de la energía y la mejora de las prestaciones sociales por la inflación pasada implican que el apoyo de la política fiscal para mitigar el impacto del encarecimiento de los alimentos y de la energía debería dirigirse únicamente a los hogares vulnerables insuficientemente cubiertos por el sistema general de protección social. Esto reforzaría los incentivos para reducir el consumo de energía y proporcionaría apoyo a la política monetaria para hacer frente a la inflación. Con una deuda pública más elevada que antes de la pandemia en la mayoría de los países, y unos gobiernos que se enfrentan a futuras necesidades de gasto debido al envejecimiento y a la transición climática, debe prestarse mayor atención a garantizar la sostenibilidad de la deuda. Reconstruir el espacio fiscal es esencial para conservar los escasos recursos a fin de cumplir las futuras prioridades políticas y responder eficazmente a futuros choques. Es necesario redoblar los esfuerzos en todas las economías para hacer frente a los principales retos estructurales, como el envejecimiento de la población, el cambio climático y la digitalización. Dada la magnitud y ubicuidad de estos retos, serán necesarias reformas audaces y sostenidas para revitalizar el crecimiento y mejorar su calidad de forma simultánea.

In advanced economies, monetary policy needs to remain restrictive for some time

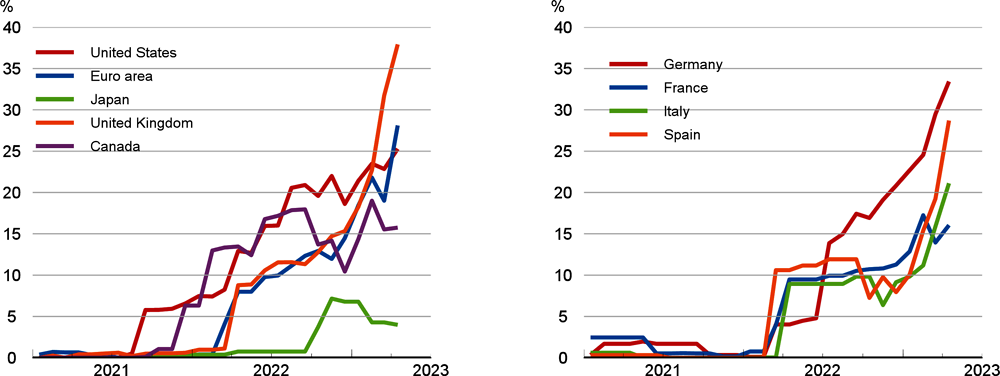

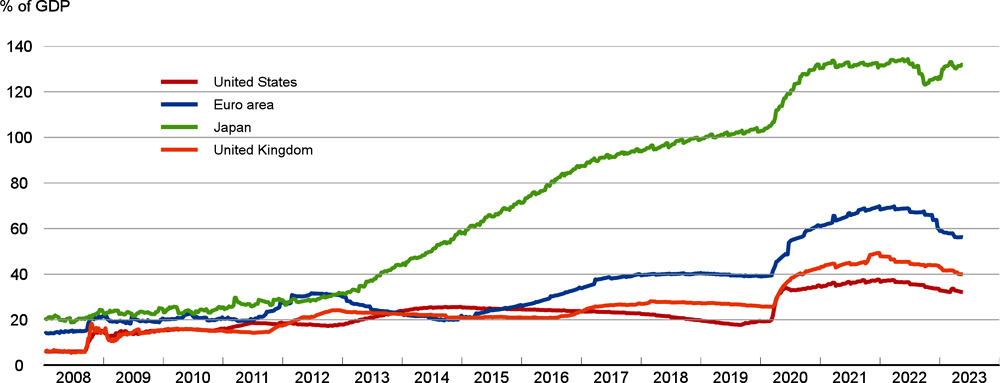

Most central banks in advanced economies have continued to tighten monetary policy in recent months, even in the aftermath of the financial market turbulence in March. Policy rate increases have nonetheless tended to become smaller, and some banks have announced a pause to assess the impact of the cumulative tightening already delivered, as forward-looking real short-term interest rates have generally now become positive. Many central banks are also now reducing securities holdings, either by not (or not fully) reinvesting the proceeds of maturing bonds (passive quantitative tightening, QT) or by selling bonds (active QT). This has helped to reduce the size of central bank balance sheets in most advanced economies, although the need for enhanced liquidity provision in the wake of the banking stress in March temporarily pushed up central bank assets in some jurisdictions (Figure 1.26).