The Real Development was the Friends We Made Along the Way

Albert Hirschman's Strategy of Economic Development

This is a new blog about development economics, and there’s surely no better way to start than by writing about Albert Hirschman—one of the pioneers of the field, and quite possibly the most interesting person to ever become an economist. Originally I set out to write a review of Albert Hirschman’s 1958 Strategy of Economic Development, but the tale grew in the telling—into a biography of Hirschman’s fascinating early life, then a broader history of development economics, and at last into a reflection on the current state of the field.

Hirschman was a master of those little ideas that, once you’ve heard them, are impossible to shake loose from your head. Because of his unconventional life story (more on that in a moment), he was an outsider for much of his academic career. Unusual for his era, he did extensive fieldwork, which helped him to develop a wry literary style that emphasized in-person observation and an allergy to sweeping mathematical models that smoothed away the messiness of human behavior. Because of these proclivities, Hirschman and his ideas were basically exiled from the mainstream of economics in the 1960s and 1970s, swept away by the rising tide of mathematization.

And precisely because of these tendencies, I think his ideas are ripe for a comeback.

The Strategy of Economic Development is a classic of offbeat Hirschmanian insight. His main idea is simple: that the “ability to make development decisions”—not capital, or labor, or any other material factor—is the limited resource constraining economic development.

If that made you scratch your head, you’re not alone. For someone conditioned to think in Lagrangians, pointing to the lack of “decision-making” as the main obstacle to economic growth feels fuzzy around the edges, a little like declaring that the real development was the friends we made along the way.

But I’ll admit that at the end of the Strategy, I was won over. This is one of those rare economics books that reconfigured my view of the world, made me reconsider views that I once considered silly, and adopt much of its language in my own thinking–so much so that I’m trying to evangelize it to you right now. How did Hirschman do it?

Hirschman’s Odyssey

It is unfashionable to talk about economists’ life stories—and truthfully, you don’t usually get more out of the latest instrumental variables procedure by knowing about the author’s childhood. But Albert Hirschman lived a life inseparable from his ideals, and to omit it would deprive you of a fascinating story.

Hirschman was born in 1915 to a well-to-do Jewish family in Berlin. He was still a teenager when he joined the Social Democratic Party, the main political opposition to the rising Nazi Party. After the Reichstag fire, with Hitler threatening to take dictatorial control, Hirschman’s cell of young activists took to the streets, passing flyers and urging people to resist. But resistance soon collapsed. With several of his friends arrested, a seventeen-year-old Hirschman was forced to flee to Paris.

In Paris, Hirschman studied at HEC, one of France’s top business schools, but found the courses dull. When a fellowship at the London School of Economics opened up, he jumped at the opportunity. As the home of Keynes, England was the shining center of the economics universe; but Hirschman instead gravitated more towards the lectures of the free-marketeers Friedrich Hayek and Lionel Robbins—an early sign of his trademark anti-ideological streak.

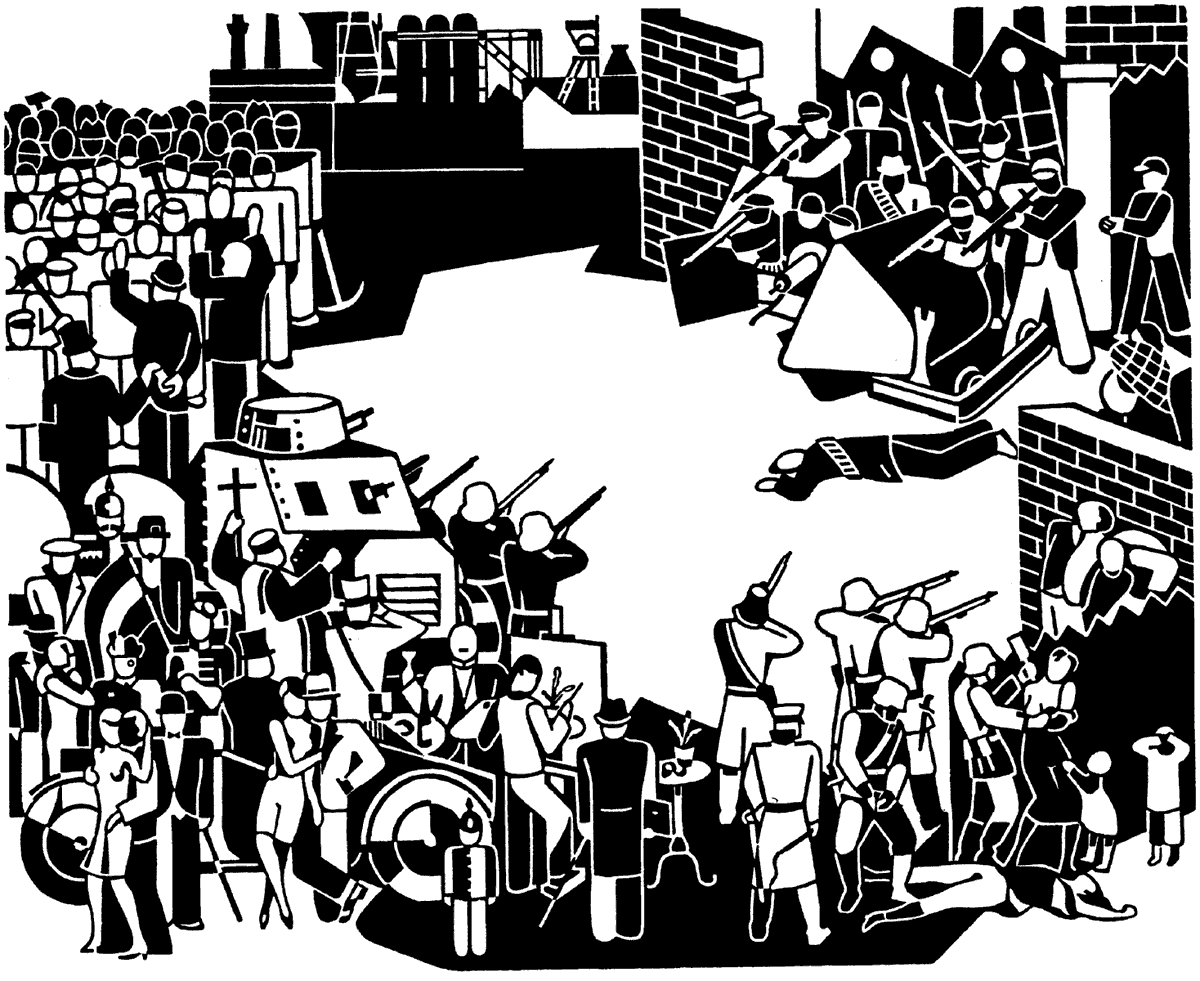

In 1936, the Spanish Civil War broke out. Almost without hesitation, Hirschman went to Spain to fight for the POUM, a Marxist group on the Republican side. Hirschman rarely spoke about his wartime experiences, even to his family, but biographer Jeremy Adelman places him at the brutal battle of Monte Pelado, a costly victory for the poorly trained Republican volunteers. He left after three months, just as another famous POUM volunteer, George Orwell, was arriving in Catalonia.

Hirschman next went to Trieste, Italy to join his sister Ursula (a noted intellectual in her own right) and his brother-in-law Eugenio Corloni. With Corloni, he became involved in the anti-Mussolini underground, carrying secret documents between France and Italy in a false-bottomed suitcase. Somehow he also found the time to finish a thesis on international economics and earn his doctorate.

Resurgent antisemitism in Italy sent him back to France. With war against Germany looming, Hirschman joined the French Army, and was trained up just in time for France to surrender. His Jewish background and history of anti-fascism made him a natural target for the Nazis, so he abandoned his uniform, took a false identity, and fled to Marseilles, which had become a haven for other refugees trying to get out of Europe.

There he met Varian Fry, an American journalist who was organizing an underground movement helping Jews and anti-Nazi refugees to escape France. Hirschman’s quick thinking, many languages, and easy charm made him an invaluable asset. Recruited by Fry, he soon became indispensable to the movement. Hirschman’s portfolio from his Marseilles days reads like something out of Casablanca: he forged passports, smuggled funds through the French criminal underground, and scoped out routes for the refugees through the Pyrenees. Only when the Vichy police began asking questions about Hirschman himself did he decide to make his discreet exit. He hiked his way over the mountains to Spain, made his way to Portugal, and from Lisbon took a ship to the United States, where a research fellowship at Berkeley was awaiting his arrival.

Over the past five years, Hirschman had fought fascism in four European countries, earning two graduate degrees along the way. Over five months in Marseilles alone, he had helped thousands of mostly Jewish refugees–including Hannah Arendt, Marc Chagall, and Marcel Duchamp–escape to safety.

Albert Hirschman was twenty-five years old.

Perhaps inevitably, Berkeley was something of a comedown from Europe. The Berkeley economics department was still frankly a backwater—the Keynesian revolution had not yet fully reached California. But Hirschman made two important acquaintances: a young scholar called Alexander Gerschenkron, also fleeing Nazi persecution, also destined to become an eminent economist; and, in the Berkeley International House cafeteria, Sarah Chapiro, a Jewish emigre from France studying literature and philosophy.

Albert and Sarah married in 1941. When it was America’s turn to go to war, Hirschman enlisted (his third army in five years), and served as a translator during the Allied invasion of Italy. Bored and underused throughout the campaign, his most notable experience was at the end of the war, when he served as the interpreter for the German general Anton Dostler during the very first Allied war crimes trial.

After returning to America, Hirschman had trouble finding work—unbeknownst to him, he was under suspicion with the FBI for his wartime leftism—but he got a hand from his old colleague Gerschenkron, who gave him a job working on the Marshall Plan at the Federal Reserve Board. Hirschman spent six productive years at the Fed, where he helped to lay the groundwork for postwar European integration. But the Hirschmans came to feel suffocated by the Washington suburbs, which were coming under the grip of McCarthy’s Red Scare. In 1951, desperate to get out, Hirschman made the surprise decision to take a job with the World Bank in Bogotá, Colombia. It would prove to be a central junction in his career.

The Big Push

Here begins Albert Hirschman’s connection to development economics. For four years Hirschman worked as an economic advisor to the Colombian government, first as a representative of the World Bank, then as a sort of freelance consultant.

By all accounts, Hirschman’s years in Bogotá were happy ones—he liked Colombia, as did Sarah and his two young girls. Despite the tragic violence of the ongoing La Violencia, Colombia was experiencing rapid economic growth, and Hirschman got the chance to work on practical problems, like advising low-cost urban housing projects and helping the Colombian government write up loan proposals for the World Bank.

But professionally, Hirschman found himself adrift. He frequently clashed with his superiors at the Bank, who condescended to their Colombian counterparts and fixated on grand economic plans based on silly formulas. Moreover, while he had aspirations of becoming a public intellectual, he was cut off from the mainstream of American economics. So when a call came from Yale offering a visiting appointment, Hirschman seized the opportunity.

His timing couldn’t have been better. Development economics was just beginning to emerge as an independent field amidst the collapse of the European colonial empires, but there was a serious shortage of economists in American schools who had actually spent time in the field. Hirschman fit the bill.

Coming into academia as an outsider, he did not like what he saw. Development economics was dominated at the time by big, sweeping theories of growth, with one-size-fits-all prescriptions.

Perhaps the most influential these was the theory of the Big Push, which Paul Rosenstein-Rodan first laid out in 1943. Think of a poor, developing country. Put down a single shoe factory in the fields, and it will likely fail due to a lack of demand, since most people will be too poor to afford the factory’s shoes. But build a cluster of factories, and you’ve given them a fighting chance—with enough factories, enough workers being paid industrial wages, and enough of them buying each other’s stuff, the market might be large enough to support itself.

The Big Push is a demand-side case of “balanced growth” theory—the idea that different parts of the economy should remain in sync as they develop. Balanced growth theories can also take supply-side forms, like stressing that manufacturing should not race ahead of agriculture, or that proper roads and infrastructure should be laid down before industrialization takes place. But, whether they’re on the demand- or supply-side, balanced growth theories largely call for the same remedy: vast programs of coordinated investment, to try and jump-start the “modern sectors” all at once.

There’s a certain theoretical elegance to the Big Push/balanced growth view of the world. It’s a close cousin of the classic Keynesian story of depressions, where if everyone tries to save at once, all we end up doing is depriving each other of income (what modern economists call a coordination failure). And, of course, there’s an undeniable political appeal. For America and its allied development agencies, looking for intellectual justifications to shore up their Cold War allies, the Big Push was music to their ears.

Slaying the Dragon

Hirschman, however, was not so easily impressed. Having seen firsthand the difficulties of getting things done on the ground—and the arrogance of foreign planners—he was skeptical of the grand promises made by the balanced growth theorists. During his fellowship at Yale, he worked furiously at a rebuttal–a project that eventually became his 1958 classic, The Strategy of Economic Development. In it, Hirschman set out to slay the dragon of the Big Push, and replace it with a theory more grounded in reality.

Hirschman’s main critique of balanced growth stems from a simple observation. “If a country were ready to apply the doctrine of balanced growth,” he writes, “then it would not be underdeveloped in the first place.” The capabilities needed to successfully kickstart the “modern sector” in one go–the systems of organization, the scientific and technical knowledge–are precisely the ones that need to be nurtured by the development process. In other words, balanced growth theory provides the correct but unhelpful diagnosis that a country’s failure to modernize stems from its lack of modernity.

Rosenstein-Rodan’s Big Push tries to solve the problem by starting the modern sector all at once, grafting it like foreign tissue onto the traditional agrarian economy. But even if the graft somehow sticks, Hirschman observes that the results can be quite unpleasant. A common outcome is a dualist economy, which you’ll still often see today around the world—a gleaming modern sector of skyscrapers and shopping malls, next to a traditional agrarian sector that remains desperately poor. Further examples are the persistent gulf in Latin America between indígenas and mestizos, and the foreign-owned plantations that are islands of “modernity” surrounded by seas of poverty.

Crucially, in the Big Push mindset of precise coordination, failure can always be chalked up to the shortage of some crucial factor (usually imported from abroad). Perhaps there was not enough cutting-edge machinery to make the power plant viable; or perhaps there was enough machinery, but more foreign experts were needed to get it running. There are so many lurking pitfalls that one can easily fall into a kind of decision paralysis.

Albert Hirschman’s main goal in the Strategy is to sidestep all of that. Here, at last, we can return to his strange central argument–that the scarce resource constraining development is not natural resources or capital or schooling or technology or any other tangible factor, but the ability to make development decisions.

Now, hopefully, this makes a little bit more sense. Rather than endlessly debate which prerequisites for growth a poor country is missing, Hirschman shifts the focus to figuring out how to make the best use of the resources it already has. But, without the guidance of a grand plan, how should policy makers decide how to allocate their attention?

The solution Hirschman proposes is unbalanced growth. Instead of trying to solve all problems all at once, policy-makers should push forward in a limited number of sectors, and use the reactions and disequilibria created by those interventions to inform their next move.

Take the example of an industrial district. With limited resources, a policymaker may have to choose between building the actual factories, or laying down the highways and power-plants (what he calls Social Overhead Capital) to supply it. Based on his theory, Hirschman makes the provocative case that infrastructure should sometimes follow, not lead, private investment:

… if we endow an underdeveloped country with a first-class highway network, with extensive hydroelectric and perhaps irrigation facilities, can we be certain that industrial and agricultural activity will expand in the wake of these improvements? Would it not be less risky and more economical first to make sure of such activity… and let the ensuing pressures determine the appropriate outlays for SOC [Social Overhead Capital] and its location?

In this example, once the industrial zone is built, it’s easy to imagine frequent blackouts and bottlenecks as trucks clog up the unimproved road. A Big Push theorist might see the disequilibria created by these initial ventures (what Hirschman calls “pressure points”) as evidence that their plan has failed. But Hirschman encourages us to flip the script. Rather than see bottlenecks and shortages as embarrassing signs of failure, policy makers can use these pressure points to identify opportunities where an additional investment might go the farthest.

With the road congested, it’s much easier to see it needs to be improved–and far better to upgrade a well-used road than build a highway to nowhere. The policy-maker, once inundated with choices, now has a clear guide on how to act. Even better, pressure points may organically summon other, non-state actors to try and address the now-glaring shortfall. Perhaps an independent power producer will spy a market opportunity, or a private railway may decide to step in and connect the factory to their network.

Hirschman formalizes this insight with his famous notion of backward and forward linkages. Backward linkages are the demand created by a new industry for its inputs, like steel for an auto plant or milk for a cheesemaker. Forward linkages are the reverse—the knock-on effects of a new industry’s outputs on the firms it supplies. Backward linkages, Hirschman goes on to explain, are better at spurring growth than forward ones. Rather than plopping down a steel factory somewhere, with no customers assured, it is far easier to build the auto plant first, sourcing the car parts from other countries as needed, then gradually entice local producers to enter the market. Instead of a Big Push across all industries at once, Hirschman calls for the Targeted Strike–choose the sectors with the most potential to create demand for other inputs, and support those.

Ahead of his time for economics, Hirschman also argues that the “nonmarket” responses induced by a policy change may be just as important as market ones. If, say, the factories in the industrial zone face a shortage of trained workers, the locals may clamor for new schools. Or if the trucks congest their neighborhood roads, they may pressure their local officials to improve the highway. Politics cannot be separated from economics when thinking about developmental choices.

Hirschman’s theory of unbalanced growth is rooted in empiricism, allowing policy makers to test and gauge the reactions of the specific context rather than applying some universal formula. It recognizes that development is naturally a chaotic, messy process, much closer to a “chain of disequilibria” than the result of a master plan. To paraphrase another important development thinker, Hirschman’s unbalanced growth is the modest call to cross the river by feeling the stones, one intervention at a time.

I could go on about the Strategy. Most modern economics papers, despite their ever-increasing length, contain only one or two ideas—the rest is just exhaustively dotting i’s and crossing t’s. Hirschman builds the Strategy around three or four big, field-changing ideas, then proceeds to drop a minor gem every couple of pages. I haven’t even mentioned his sly anthropological observations on nepotistic factory managers (“the last-ditch stand for [the] right to a quiet, incompetent existence”), or his canny prediction that developing countries should promote their exports in order to ease their balance-of-payments problems. There is a wealth of insight in The Strategy of Economic Development—one of those rare books that makes it impossible to see the world in the same way after reading it.

So why, then, has it been out of print for decades?

The Wilderness

Hirschman is still read today in political science and sociology, but hardly ever in economics, and even less in his home discipline, development. Backward and forward linkages have been incorporated into the conceptual language of economics, but Hirschman’s original, broader usage is long forgotten. Probably the only time his name actually comes up is the Herfindahl-Hirschman index used to study industrial concentration–but often we just shorten it to the Herfindahl index. (For the record, Hirschman came up with it first.)

In his classic 1995 essay, “the Fall and Rise of Development Economics”, Paul Krugman carved out the epitaph for Hirschman’s intellectual legacy—what he called “the High Development Theory”, of which the Strategy represented the high-water mark. The coup de grace had been delivered long ago, by economics’s mathematical turn:

High development theorists were having a hard time expressing their ideas in the kind of tightly specified models that were increasingly becoming the unique language of discourse of economic analysis. They were faced with the choice of either adopting that increasingly dominant intellectual style, or finding themselves pushed into the intellectual periphery. They didn’t make the transition, and as a result high development theory was largely purged from economics, even development economics…

Along with some others, notably Myrdal, Hirschman didn’t wait for intellectual exile: he proudly gathered up his followers and led them into the wilderness himself. Unfortunately, they perished there.

For his part, Hirschman knew the direction economics was heading. Hirschman’s biographer Jeremy Adelman notes that he was anxious to show his mathematical chops—the Strategy is scattered with stray equations as if to remind you of its seriousness. (Graduate students everywhere can surely relate.) But the math in the Strategy is ultimately ornamental; nothing is conveyed that isn’t already in the words. Hirschman eventually gave up on formal economic modeling, a path Krugman believes led to academic obscurity.

The bulk of Krugman’s essay is concerned with showing that this exile was unnecessary—many of the ideas of High Development could have easily been translated to the language of mathematics. To show just how easy it is, in a few pages Krugman works out Murphy, Shleifer and Vishny’s 1989 model of industrialization, which formalizes Rosenstein-Rodan’s 1943 insight about the Big Push. The algebra is straightforward; the model elegantly simple–nothing that the perfectly capable theoreticians of the 1950s couldn’t have done, had they known a few small tricks. (A minor inconvenience for Krugman’s account is that Rosenstein-Rodan’s “Big Push” was precisely the theory Hirschman’s Strategy was trying to debunk. But no need to stand in the way of a good story.)

Reading Krugman carefully, one can sense the intellectual tension: he sympathizes with Hirschman and admires his insight, but his loyalties ultimately lie with the advances in mathematical theory that seemed so triumphant in the 1990s. As a result, he concludes on a strangely ambivalent note:

The truth is, I fear, that there’s not much that can be done about the kind of apparent intellectual waste that took place during the fall and rise of development economics. A temporary evolution of ignorance may be the price of progress, an inevitable part of what happens when we try to make sense of the world’s complexity.

But what Krugman sees as a sad inevitability of the march of progress could just as easily be recast as a disastrous loss of knowledge. Nothing prevents economists from reading old books!

Within a few years of Krugman’s article, it was clear that development economics was stuck in a rut. Read William Easterly’s 2001 The Elusive Quest for Growth, a good summation of development thinking at the time, and the prevailing sense one gets is of frustration. According to Easterly, nothing seemed to work—not aid, not debt relief, and certainly not any of Jeffrey Sachs’s ideas. The highly-touted growth models of the 1990s proved to be not much help. Murphy, Shleifer, and Vishny 1989 is still well-cited, but has not become one of the standard models economists use to think about development. It is still respectfully included in many graduate syllabi, but more as a kind of curio, an evolutionary dead-end. More to the point, it’s doubtful that the paper’s much-vaunted algebra swayed any politician who wasn’t already convinced by the rhetoric of the Big Push.

In hindsight the unlearning of Hirschman’s ideas seem more like victims of economists’ rigid insistence that evidence take the form of mathematical models than necessary casualties of science. Indeed, post-2008 Krugman has made a second career publicly decrying the Dark Age of Macroeconomics—the deliberate forgetting of the hard-won Keynesian ideas of the Great Depression. It would be interesting to hear what he would make of this essay today.

The Friends We Made Along The Way

Far too many Wisdom of the Ancients pieces—those op-eds that claim Adam Smith had it all right, if only you hadn’t dozed through The Wealth of Nations; or Marx saw it all coming, it’s just all in the endnotes to Capital Volume III–end up wringing their hands in despair, bemoaning what their chosen prophet would think if they saw the state of economics today.

But not so with Albert Hirschman.

Since Krugman wrote his 1995 essay, development economics has undergone another intellectual upheaval. Highly formalized growth models are still around, but the center of gravity has shifted decisively towards randomized control trials (RCTs) and micro-level evidence—a more Hirschmanian approach if there ever was one. The 2019 Nobel Prize to Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo, and Michael Kremer was, in a sense, just a belated recognition of this de facto intellectual triumph.

The methodological switch to RCTs has not been without controversy; I’ll leave that whole debate aside for another time. But the randomista revolution remains underrated in one crucial respect. Running RCTs has forced a whole generation of economists to leave their desks, go to the countries they study, and talk to the people who live there. In Chris Blattman’s words, we’re all Hirschman now—tramping through fields, collecting our own data, trying our best to not let theory obscure the evidence of our eyes. It’s not hard to see Hirschman’s ghost wandering through the Busia offices of Innovations for Poverty Action, nodding his head in wry approval.

Not to say that we’re perfect; nor even to say that we should seek approval from this defunct economist. For his part, I suspect that Hirschman would like development to use more qualitative evidence, and speak more to other social sciences, like sociology and anthropology. He would also probably wish that more economists finally learned to write better.

On our side, we should not underrate what we’ve learned since Hirschman’s time. For instance, while Hirschman takes the novel step of integrating politics into his analysis of pressure points, he tends to view it in rather antiseptic terms, treating it as a force that responds neatly to demands and pressures from the population. Writing in 1958, his view of development does not yet anticipate the likes of Mobutu Sese Seko or Ferdinand Marcos–or the continued US support that made their misrule possible. (Hirschman later returned to partly correct this oversight in his classic Exit, Voice, and Loyalty.)

On the other hand, failure to predict the future is forgivable—after all, we’re economists here. The more severe omission of the Strategy comes from Hirschman’s failure to look backwards. Hirschman was by temperament an optimist, more interested in finding solutions for poverty than wondering why people were poor in the first place. But the developing world of the 1950s was far from a blank slate. History is almost entirely absent from the Strategy. There are snippets, here and there, that suggest a broader awareness of the scars wrought by colonialism—like when Hirschman laments the division between indígenas and mestizos in Peru—but he never really advances the view that the lack of decision-making capacity may stem from these deep historical causes. It’s a shame.

Still, writing as a young economist, the continued relevance of the Strategy to development seems clear. He encourages us to see the inevitable pitfalls and stumbles of the growth process not as disappointments, but as opportunities, and gives us a conceptual language to identify them. For randomistas-in-training, steeped in the world of deworming and bed-nets and pre-analysis plans, Hirschman also reminds us that we need to step back from individual interventions more often and think more about development strategies–not just how different projects can complement each other, but also how each project might organically summon market and non-market forces to help growth along.

The Credibility Revolution has yielded, perhaps for the first time, robust evidence for individual program effects. The time is ripe, not to copy Hirschman’s ideas wholesale, but to borrow his clear-eyed approach and think carefully about how projects can be brought together, pressure point by pressure point, into programs for sustained development.

this post originally appeared on my academic website in 2021. If you enjoyed this post, I highly recommend Jeremy Adelman’s biography of Hirschman, Worldly Philosopher, which was my main source. Here’s Adelman talking to Cardiff Garcia on one of the FT’s podcasts.

https://www.global-developments.org/p/the-real-development-was-the-friends

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario