The simple economics of panic: The 2022 Nobel Prize in perspective

El Premio Nobel de Ciencias Económicas de 2022 fue concedido a Ben Bernanke y a Douglas Diamond y Philip Dybvig, en gran parte en honor a los trabajos que publicaron en 1983. Esta columna aborda las críticas de que Diamond y Dybvig no hicieron nada más que formalizar matemáticamente algo que todo el mundo ya sabía, o debería haber sabido, y que Bernanke fue recompensado menos por su investigación que por su posterior papel como responsable político.

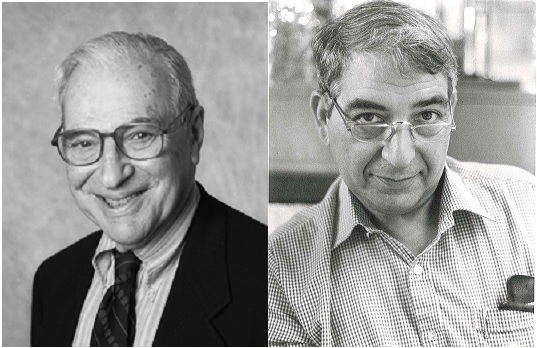

El Premio Nobel de Economía de 2022 recayó en Ben Bernanke, un nombre muy conocido, y en Douglas Diamond y Philip Dybvig, que eran en gran medida desconocidos para el público pero inmensamente influyentes dentro de la profesión. Pocos economistas predijeron la crisis financiera de 2008, pero cuando ocurrió, a pocos les pareció desconcertante; en los días posteriores a la caída de Lehman, se podía encontrar a los economistas recorriendo los pasillos de sus departamentos, murmurando "Diamond-Dybvig, Diamond-Dybvig".

El premio de este año era, en cierto modo, inusual. Los premios Nobel de las ciencias duras suelen concederse por un trabajo de investigación importante; los de economía suelen ser más bien premios a toda una vida. Esta vez, sin embargo, el premio honró en gran medida un trabajo seminal, "Bank Runs, Deposit Insurance, and Liquidity" de Diamond y Dybvig de 1983, junto con el trabajo de Bernanke del mismo año, "Nonmonetary Effects of the Financial Crisis in the Propagation of the Great Depression".

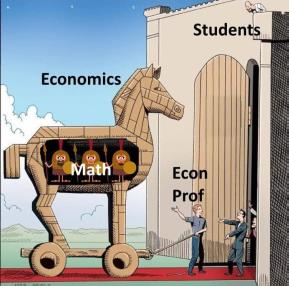

El premio también ha generado cierta controversia, en dos frentes. Los economistas heterodoxos y los historiadores han argumentado que Diamond y Dybvig no hicieron más que formalizar matemáticamente algo que todo el mundo ya sabía, o debería haber sabido. Al mismo tiempo, se han planteado algunas preguntas sobre si Bernanke fue recompensado menos por su investigación que por su posterior papel como responsable de la política económica.

Sobre la primera cuestión, argumentaré que los críticos están equivocados, no sólo porque la formalización importa, sino porque Diamond-Dybvig ofreció un mensaje bastante diferente al de escritores más discursivos como Hyman Minsky y Charles Kindleberger. La segunda crítica, como explicaré, plantea cuestiones más sutiles sobre el papel de los economistas que se convierten en servidores públicos.

Empecemos por lo que hicieron Diamond y Dybvig.

El modelo Diamond-Dybvig

Diamond y Dybvig (1983) es un trabajo relativamente corto y bastante sencillo en comparación con muchos trabajos de teoría económica. De hecho, podría decirse que es un artículo demasiado simple para ser publicado hoy en día. ¿Dónde están los análisis de sensibilidad, los cálculos numéricos, etc.? Pero proporciona un análisis revelador tanto de la banca como de las corridas bancarias, con amplias implicaciones para aquellos que capten su mensaje.

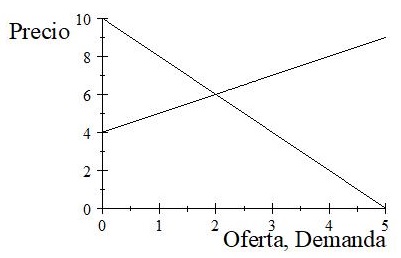

El análisis de Diamond-Dybvig parte de la idea de una compensación - una compensación real, no algo meramente financiero - entre la liquidez y la rentabilidad. Los individuos saben que pueden enfrentarse a necesidades imprevisibles de poder adquisitivo actual, por ejemplo, debido a emergencias sanitarias; sin embargo, el capital productivo es a menudo difícil o imposible de vender a corto plazo. En ausencia de intermediarios financieros, el deseo de liquidez impondría costes reales, porque una parte importante de los ahorros tendría que dedicarse a inversiones líquidas con bajo rendimiento.

Los intermediarios financieros -llámense bancos, aunque no tienen por qué parecerse a los bancos convencionales- pueden resolver este problema vendiendo pasivos líquidos (depósitos bancarios, o algo parecido a los depósitos bancarios) que pueden convertirse en efectivo con poca antelación, mientras invierten sobre todo en activos ilíquidos pero de alta rentabilidad. Esto suele funcionar porque la necesidad de efectivo, aunque impredecible a nivel individual, es mucho más predecible en conjunto, de modo que una cantidad modesta de inversión líquida -reservas bancarias o su equivalente- es suficiente para satisfacer las demandas normales.

Desgraciadamente, como señalaron Diamond y Dybvig, un sistema en el que los intermediarios financieros toman prestado líquido pero invierten ilíquido tiende a tener múltiples equilibrios. Si todo el mundo espera que el sistema funcione, lo hace. Pero si la gente llega a esperar que otras personas retiren fondos en masa, se apresurarán a retirar también sus propios fondos, rompiendo los bancos que no pueden liquidar fácilmente sus inversiones.

La posibilidad de un mal equilibrio crea un papel para la política pública. Los gobiernos y las entidades cuasi-gubernamentales, como los bancos centrales, pueden evitar los pánicos autocumplidos actuando como prestamistas de última instancia, asegurando los depósitos bancarios, etc.

Así pues, Diamond-Dybvig demostró, en un modelo minimalista, que la banca es una actividad productiva, pero que también crea un riesgo sistémico a menos que esté respaldada por una red de seguridad pública. Y de esta idea se derivan muchas otras cosas.

Lo que nos dice el modelo

A pesar de su simplicidad, Diamond-Dybvig tiene implicaciones extraordinariamente amplias tanto para el análisis económico como para la política económica. Podría decirse que la falta de comprensión de estas implicaciones a lo largo de las décadas de 1990 y 2000 contribuyó a preparar el terreno para la crisis financiera de 2008; pero la rápida, aunque tardía, apreciación de estas implicaciones por parte de los responsables políticos, Bernanke entre ellos, ayudó al mundo a evitar una repetición de la Gran Depresión.

En primer lugar, Diamond-Dybvig deja claro que un intermediario financiero no tiene por qué ser un banco en un sentido legal o convencional -no necesita ser una institución de depósito- para estar sujeto a la posibilidad de corridas bancarias de facto. Cualquier agente financiero con pasivos líquidos pero con activos ilíquidos se encuentra en la posición de servir una función económica útil pero planteando el riesgo de un pánico autocumplido.

Aprendimos esta lección por la vía difícil en 2007-08. Los economistas se mostraban generalmente optimistas sobre los riesgos financieros, porque creían - correctamente - que las instituciones de depósito estaban protegidas por una red de seguridad adecuada. De hecho, apenas se produjeron retiradas de fondos en las instituciones cubiertas por la Corporación Federal de Seguros de Depósitos (FDIC). Sin embargo, se produjeron retiradas de fondos del mercado monetario, bancos de inversión que emitían reposiciones y otros "bancos en la sombra", es decir, instituciones que eran bancos en el sentido de Diamond-Dybvig, pero que no contaban con un seguro de depósitos ni tenían acceso tradicional a los préstamos de la Reserva Federal.

En relación con esto, Diamond-Dybvig deja claro que la razón por la que las corridas bancarias perjudican a la economía no es, como mucha gente ha supuesto, que reduzcan el multiplicador del dinero y, por tanto, la oferta monetaria. De hecho, el modelo de Diamond-Dybvig no es explícitamente monetario en absoluto; la pérdida de una corrida bancaria proviene de la destrucción de riqueza real. Y la desconexión entre su análisis y la preocupación por los agregados monetarios queda aún más clara cuando se piensa en la crisis de 2008, que afectó en gran medida a los bancos en la sombra, cuyos pasivos, a diferencia de los depósitos de los bancos convencionales, no se contabilizan en la oferta monetaria.

Por último, Diamond-Dybvig aboga por la regulación financiera, no sólo para las instituciones de depósito, sino para todos los intermediarios financieros que participan en la transformación de la liquidez. Todas estas instituciones necesitan tener acceso a algún tipo de red de seguridad para evitar el pánico autocumplido; pero la provisión de una red de seguridad crea un riesgo moral, por lo que debe ir acompañada de regulaciones diseñadas para limitar la explotación de este riesgo moral. Esto puede ser un problema complicado en la práctica: ¿Cómo saber qué instituciones requieren regulación? La Ley Dodd-Frank de Estados Unidos, introducida tras la crisis de 2008, regula las instituciones "sistémicamente importantes", pero ¿cómo se identifican dichas instituciones? Básicamente se basa en una prueba de pornografía: uno (o más bien un comité de funcionarios del gobierno) lo reconoce cuando lo ve. Pero en cualquier caso, Diamond-Dybvig proporciona la justificación intelectual.

Pero, ¿hacía falta un modelo formal estilizado para ofrecer estas ideas?

¿Estaba todo en Minsky?

El Nobel de 2022 se ha enfrentado a algunas duras críticas, especialmente por parte del historiador Adam Tooze, que atacó el premio como una especie de encubrimiento del fracaso de los economistas de la corriente principal "para tomar en serio a los pensadores que se enfrentan a la importancia esencial de las finanzas y sus peligros para el mundo moderno de frente", como Hyman Minsky y Charles Kindleberger (Tooze 2022).

¿Es justa esta acusación?

Obviamente, Diamond y Dybvig no descubrieron las corridas bancarias, ni su naturaleza autocumplida. De hecho, se podría considerar su análisis como una formalización del tema central del libro de Walter Bagehot de 1873, Lombard Street. Pero la formalización desempeña un papel importante en la economía, ya que ayuda a identificar los puntos esenciales en exposiciones más discursivas, que a menudo pueden parecer -y con demasiada frecuencia lo son- ensalada de palabras sin implicaciones claras.

En cuanto a Minsky y Kindleberger, revisar su trabajo es darse cuenta de que estaban haciendo algo muy diferente a Diamond-Dybvig.

La hipótesis de la "inestabilidad financiera" de Minsky, adoptada por Kindleberger en ediciones posteriores de su obra Manias, Panics, and Crashes, contaba una historia de ciclos maníaco-depresivos en el comportamiento financiero. Una época de estabilidad financiera engendra un exceso de confianza, luego una exuberancia irracional, que lleva a un aumento del apalancamiento y, finalmente, a una caída; entonces el ciclo vuelve a empezar.

Sin embargo, Diamond y Dybvig demostraron que las corridas bancarias destructivas pueden producirse incluso en un sistema financiero fundamentalmente sólido; no tienen por qué ser el resultado de la locura del pasado y del exceso de apalancamiento. Y la respuesta política debería centrarse más en contener los riesgos de pánico que en prevenir los excesos financieros.

Hay un fuerte paralelismo aquí con la teoría del ciclo económico antes y después de Keynes. Los analistas prekeynesianos -muchos de ellos resumidos en Haberler (1937)- se preguntaban "¿Por qué tenemos auges y caídas?", y ofrecían historias de periodos alternados de exuberancia y miedo, no muy diferentes del relato de Minsky. Siendo la naturaleza humana lo que es, estos analistas tendían a la prurito, prodigando el tiempo en los excesos del auge más que en la cuestión de por qué tales excesos debían conducir no sólo al despilfarro, sino al desempleo masivo.

Keynes, sin embargo, dedicó gran parte, aunque no toda, la Teoría General a abordar una cuestión muy diferente: "¿Cómo puede una economía permanecer deprimida durante largos períodos?" Esto puso el énfasis en la depresión en sí misma, no en los excesos que pueden o no haberla precedido.

No en vano, el enfoque de Keynes proporcionó una orientación política mucho más útil. Los teóricos prekeynesianos se preguntaban qué había que hacer con la Gran Depresión, ofrecían pocas propuestas claras y a menudo se oponían a los estímulos monetarios y fiscales por temor a que fomentaran más excesos. Los keynesianos dijeron, en efecto, "aprieta este botón", es decir, proporciona estímulo. Y tenían razón.

Del mismo modo, la hipótesis de la inestabilidad financiera puede ayudar a dar sentido a la historia y servir como un útil correctivo a la complacencia, pero no ofrece mucha orientación sobre lo que debemos hacer. Diamond-Dybvig, con su claro argumento a favor de las redes de seguridad financiera y la regulación financiera, es, a pesar de lo abstracto de su modelo, más práctico que los extensos debates verbales y los diagramas de flujo que muestran muchas flechas que conectan muchas cajas.

Así pues, las críticas que describen a Diamond-Dybvig como un mero ejercicio matemático sobre lo que todo el mundo ya sabía, y el premio de este año como un anuncio de las debilidades de los economistas, no de sus puntos fuertes, se equivocan en varios aspectos. Diamond-Dybvig fue una contribución importante que cambió la forma en que todo el mundo pensaba en las finanzas.

¿Y Bernanke?

El documento de Ben Bernanke de 1983 sobre los efectos macroeconómicos de la crisis financiera fue una pieza importante de investigación. Si me disculpan la metáfora, puso carne empírica en los huesos del modelo Diamond-Dybvig. Proporcionó un poderoso, aunque implícito, rechazo de la afirmación de Friedman-Schwarz (1963) de que las fuerzas monetarias causaron la Depresión. En resumen, era un artículo importante.

Pero, ¿importó de la misma manera que Diamond-Dybvig? Los premios Nobel de economía se conceden, en su mayor parte, a trabajos que cambian radicalmente nuestra comprensión: artículos y libros que, una vez leídos, cambian permanentemente la forma de pensar sobre el mundo. Diamond y Dybvig cumplen claramente ese requisito. No es obvio que el trabajo de Bernanke, por excelente que sea, haya superado ese listón. Por lo tanto, es comprensible la sospecha de que Bernanke fue recompensado en cierta medida por su papel heroico como responsable de la política en contraposición a su investigación académica.

Por otra parte, Bernanke fue un importante investigador antes de pasar a la Reserva Federal, haciendo más que nadie para incorporar el papel de las finanzas en la macroeconomía. Así que no es que darle el Nobel sea en absoluto absurdo o indefendible.

Y definitivamente no queremos caer en la trampa de devaluar la investigación académica a posteriori porque los investigadores en cuestión tuvieron segundos actos en sus vidas, pasando a la formulación de políticas, a la política o, sí, al periodismo. El trabajo debe ser juzgado por sus propios méritos, no por lo que su autor hizo después.

Así que añadir a Bernanke al premio fue un poco extraño, pero, como dije, defendible.

Un premio para nuestro tiempo

Lo que más llama la atención del Nobel de 2022 es su relevancia, a pesar de que los artículos fundamentales en los que se basa el premio se publicaron hace casi 30 años. Los pánicos financieros han desempeñado un enorme papel en la economía del siglo XXI, y no sólo en 2008. La crisis de la zona euro de 2011-12 parece tener fuertes elementos de pánico autocumplido; lo mismo ocurrió con la reciente agitación en el mercado de bonos de Gran Bretaña. Ninguna de estas crisis se ajusta exactamente a los análisis de Diamond-Dybvig-Bernanke, pero en cada caso nuestra comprensión de lo que estaba sucediendo estaba muy moldeada por lo que podríamos llamar un marco mental de Diamond-Dybvig-Bernanke.

Así que este fue un Nobel importante y bien justificado. Que nadie les diga lo contrario.

The 2022 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences went to Ben Bernanke and Douglas Diamond and Philip Dybvig, largely in honour of papers they published in 1983. This column addresses criticisms that Diamond and Dybvig did nothing but mathematically formalise something everyone already knew, or should have known, and that Bernanke was rewarded less for his research than for his later role as a policymaker.

The 2022 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences went to Ben Bernanke, a household name, and Douglas Diamond and Philip Dybvig, who were largely unknown to the public but immensely influential within the profession. Few economists predicted the 2008 financial crisis, but when it happened, few found it baffling; in the days after the fall of Lehman, economists could in effect be found roaming the halls of their departments, muttering “Diamond-Dybvig, Diamond-Dybvig.”

This year’s prize was, in a way, unusual. Nobel prizes in the hard sciences are generally given for one important piece of research; economics Nobels are typically more like lifetime achievement awards. This time, however, the award largely honoured one seminal paper, Diamond and Dybvig’s 1983 “Bank Runs, Deposit Insurance, and Liquidity,” together with Bernanke’s paper of the same year, “Nonmonetary Effects of the Financial Crisis in the Propagation of the Great Depression.”

The prize has also generated some controversy, on two fronts. Heterodox economists and historians have argued that Diamond and Dybvig did nothing but mathematically formalise something everyone already knew, or should have known. At the same time, there have been some questions raised about whether Bernanke was rewarded less for his research than for his later role as a policymaker.

On the first question, I’ll argue that the critics are wrong — not just because formalisation matters, but because Diamond-Dybvig offered a quite different message from that of more discursive writers like Hyman Minsky and Charles Kindleberger. The second critique, as I’ll explain, raises subtler issues about the role of economists who become public servants.

Let’s start with what Diamond and Dybvig did.

The Diamond-Dybvig model

Diamond and Dybvig (1983) is a relatively short paper, and fairly simple compared with many papers in economic theory. Indeed, it’s arguably a paper too simple to get published these days. Where’s the sensitivity analysis, the number-crunching, etc.? But it provided a mind-opening analysis both of banking and of bank runs, with wide implications for those who got its message.

The Diamond-Dybvig analysis starts with the idea of a trade-off — a real trade-off, not something merely financial — between liquidity and returns. Individuals know that they may face unpredictable needs for current purchasing power, say, because of health emergencies; however, productive capital is often hard or impossible to sell on short notice. In the absence of financial intermediaries, the desire for liquidity would impose real costs, because a significant part of savings would have to be devoted to liquid investments with low yield.

Financial intermediaries — call them banks, although they needn’t look like conventional banks — can resolve this problem by selling liquid liabilities (bank deposits, or something like bank deposits) that can be converted into cash on short notice, while investing mostly in illiquid but high-return assets. This usually works because the need for cash, while unpredictable at the level of the individual, is much more predictable in aggregate, so that a modest amount of liquid investment — bank reserves or their equivalent — is sufficient to meet normal demands.

Unfortunately, as Diamond and Dybvig pointed out, a system in which financial intermediaries borrow liquid but invest illiquid tends to have multiple equilibria. If everyone expects the system to work, it does. But if people come to expect other people to withdraw funds en masse, they will rush to withdraw their own funds too, breaking banks that can’t easily liquidate their investments.

The possibility of a bad equilibrium creates a role for public policy. Governments and quasi-governmental entities like central banks can prevent self-fulfilling panics by acting as lenders of last resort, insuring bank deposits and more.

So Diamond-Dybvig showed, in a minimalist model, that banking is a productive activity but also one that creates systemic risk unless backed by a public safety net. And from that insight, a lot of other things follow.

What the model tells us

Despite its simplicity, Diamond-Dybvig has remarkably broad implications both for economic analysis and for economic policy. Arguably, failure to understand these implications over the course of the 1990s and 2000s helped set the stage for the 2008 financial crisis; but the quick, if belated, appreciation of these implications by policymakers, Bernanke very much among them, helped the world avoid a repetition of the Great Depression.

First, Diamond-Dybvig makes it clear that a financial intermediary needn’t be a bank in a legal or conventional sense — it needn’t be a depository institution — to be subject to the possibility of de facto bank runs. Any financial player with liquid liabilities but illiquid assets is in the position of serving a useful economic function but posing the risk of self-fulfilling panic.

We learned this lesson the hard way in 2007–08. Economists were generally sanguine about financial risks, because they believed — correctly — that depository institutions were protected by an adequate safety net. Indeed, there were hardly any runs on institutions covered by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). But there were runs on money market funds, investment banks that issued repo, and other ‘shadow banks’ — institutions that were banks in the Diamond-Dybvig sense, but didn’t have deposit insurance or traditional access to Fed lending.

Relatedly, Diamond-Dybvig makes it clear that the reason bank runs damage the economy is not, as many people have supposed, that they reduce the money multiplier and hence reduce the money supply. In fact, the Diamond-Dybvig model isn’t explicitly monetary at all; the loss from a bank run comes from real wealth destruction. And the disconnect between their analysis and concern about monetary aggregates becomes even clearer when you think about the 2008 crisis, which largely hit shadow banks whose liabilities, unlike the deposits of conventional banks, aren’t counted in the money supply.

Finally, Diamond-Dybvig makes the case for financial regulation, not just for depository institutions, but for all financial intermediaries that engage in liquidity transformation. All such institutions need access to some kind of safety net to rule out self-fulfilling panic; but provision of a safety net creates moral hazard, so it needs to go along with regulations designed to limit the exploitation of this moral hazard. This can be a tricky problem in practice: How do you know which institutions require regulation? America’s Dodd-Frank Act, introduced after the 2008 crisis, regulates “systemically important” institutions, but how are such institutions identified? Essentially it relies on a pornography test: you (or rather a committee of government officials) know it when you see it. But in any case, Diamond-Dybvig provides the intellectual justification.

But did we need a stylised formal model to deliver these insights?

Was it all in Minsky?

The 2022 Nobel has faced some harsh criticism, notably by the historian Adam Tooze, who attacked the prize as a sort of coverup for mainstream economists’ failure “to take seriously thinkers who face the essential important of finance and its dangers for the modern world head on,” such as Hyman Minsky and Charles Kindleberger (Tooze 2022).

Is this accusation fair?

Obviously, Diamond and Dybvig didn’t discover bank runs, or their self-fulfilling nature. Indeed, you might consider their analysis a formalisation of the central theme of Walter Bagehot’s 1873 book Lombard Street. But formalisation plays an important role in economics, helping to pick out the essential points in more discursive expositions, which can often seem to be — and all too often are — word salad with no clear implications.

As for Minsky and Kindleberger, to revisit their work is to realise that they were doing something quite different from Diamond-Dybvig.

Minsky’s “financial instability” hypothesis, adopted by Kindleberger in later editions of his Manias, Panics, and Crashes, told a story of manic-depressive cycles in financial behaviour. An era of financial stability breeds overconfidence, then irrational exuberance, which leads to rising leverage and eventually to a crash; then the cycle starts again.

Diamond and Dybvig showed, however, that destructive bank runs can happen even in a fundamentally sound financial system — they don’t have to be the result of past folly and too much leverage. And the policy response should focus more on containing the risks of panic than on preventing financial excesses.

There’s a strong parallel here with business cycle theory before and after Keynes. Pre-Keynesian analysts — many of them summarised in Haberler (1937) — asked “Why do we have booms and busts?”, and offered stories of alternating periods of exuberance and fear, not that different from the Minsky account. Human nature being what it is, these analysts tended toward prurience, lavishing time on the excesses of the boom rather than on the question of why such excesses should lead not just to waste, but to mass unemployment.

Keynes, however, spent much, though not all, of The General Theory addressing a quite different question: “How can an economy remain depressed for long periods?” This placed the emphasis firmly on the slump itself, not the excesses that may or may not have preceded it.

Not incidentally, Keynes’s focus provided much more useful policy guidance. Pre-Keynesian theorists asked what should be done about the Great Depression, offered little in the way of clear proposals, and often opposed monetary and fiscal stimulus out of concern that it would encourage more excess. Keynesians said, in effect, “push this button” — i.e. provide stimulus. And they were right.

Similarly, the financial instability hypothesis may help make sense of history and serve as a useful corrective to complacency, but it doesn’t offer much guidance about what we should do. Diamond-Dybvig, with its crystal-clear case for financial safety nets plus financial regulation, is, for all the abstractness of its model, more practical than sprawling verbal discussions and flow charts showing lots of arrows connecting lots of boxes.

So, criticism that portrays Diamond-Dybvig as simply doing fancy maths on what everyone already knew, and this year’s prize as an advertisement for economists’ weaknesses, not their strengths, misses the point in several ways. Diamond-Dybvig was a major contribution that changed the way everyone thought about finance.

What about Bernanke?

Ben Bernanke’s 1983 paper on the macroeconomic effects of financial crisis was an important piece of research. If you’ll excuse my metaphor, it put empirical meat on the bones of the Diamond-Dybvig model. It provided a powerful, if implicit, rejection of the Friedman-Schwarz (1963) claim that monetary forces caused the Depression. It was, in short, a paper that mattered.

But did it matter the way Diamond-Dybvig mattered? Nobels in economics are, for the most part, given for work that dramatically changes our understanding — papers and books that, once read, permanently change how one thinks about the world. Diamond and Dybvig clearly meets that threshold. It’s not obvious that Bernanke’s work, excellent as it was, cleared that bar. So, there’s some understandable suspicion that Bernanke was to some extent rewarded for his heroic role as a policymaker as opposed to his academic research.

On the other hand, Bernanke was an important researcher before he moved to the Federal Reserve, doing more than anyone else to incorporate the role of finance into macroeconomics. So it’s not as if giving him the Nobel is in any way absurd or indefensible.

And we definitely don’t want to fall into the trap of devaluing academic research after the fact because the researchers in question had second acts in their lives, moving on to policymaking, politics, or, yes, journalism. The work should be judged on its own merits, not by what its author did later.

So adding Bernanke to the prize was a bit odd, but, as I said, defensible.

A prize for our time

What’s really striking about the 2022 Nobel is how relevant it seems, even though the seminal papers behind the prize were published almost 30 years ago. Financial panics have played a huge role in the 21st-century economy — and not just in 2008. The euro area crisis of 2011–12 seems to have strong elements of self-fulfilling panic; so did the recent turmoil in Britain’s bond market. Neither of these crises fits the Diamond-Dybvig-Bernanke analyses exactly, but in each case our understanding of what was going on was very much shaped by what we might call a Diamond-Dybvig-Bernanke frame of mind.

So this was an important and well-justified Nobel. Don’t let anyone tell you it wasn’t.

References

Bagehot, W (1873), Lombard Street.

Bernanke, B (1983), “Nonmonetary Effects of the Financial Crisis in the Propagation of the Great Depression”, American Economic Review 73(3): 257-276.

Diamond, D and D, Philip (1983), “Bank Runs, Deposit Insurance, and Liquidity,” Journal of Political Economy 91(3): 401-419.

Friedman, M and A Schwartz (1963), A Monetary History of the United States.

Haberler, G (1937), Prosperity and Depression, League of Nations.

Kindleberger, C (1978), Manias, Panics and Crashes.

Minsky, H (1986), Stabilizing an Unstable Economy.

Tooze, A (2022), “Kindleberger, Mehrling and that Nobel Prize”, Chartbook, 14 October.

https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/simple-economics-panic-2022-nobel-prize-perspective

https://brujulaeconomica.blogspot.com/2022/10/premio-nobel-economia-2022-ben-s.html

So we've returned to full employment, but with unacceptably high inflation. And inflation is bad because it reduces real wages — right? Actually, the facts if you compare the current situation with pre pandemic, are kind of surprising

Two wage measures: overall and nonsupervisory (regular people). Two price measures: overall and excluding food and energy, which are not much affected by policy

So real wages of nonsupervisory workers actually higher than pre pandemic; real wages overall slightly down, but that's entirely bc of food and energy, driven by forces outside the US. Not the story you've probably heard

But won't bringing inflation down require a nasty recession. Maybe, or maybe not — that's an assertion, not a fact. And the standard economic model of stagflation, which depends on expectations, actually says not, since expected inflation hasn't risen much

In short, there's a pretty good probability that we'll look back on how America handled the pandemic shock, mostly under Biden, and see it as a big success story

https://twitter.com/paulkrugman/status/1586814573801250817