Una interpretación desde el campo post-keynesiano del aumento reciente de la inflación.

Some controversies in the causes of the post-pandemic inflation

Marc Lavoie

University of Ottawa, Canada, and Université Sorbonne Paris Nord, France

“In general, the rise in profits and the profit share can be explained without resorting to an explanation based on firms taking advantage of the situation and raising markup rates. In other words, this third explanation denies the generalized existence of profit inflation.”

The topic of inflation, after a long hiatus, is back in fashion. Current inflation is now being explained through two broad stories. The intent of this blog is to develop a third story, less visible in the blogosphere and in academia. There could be a fourth thesis, associated with rising inflation being caused by excessive wage increases, but there is zero evidence of this (so far), with the exception of a brisk increase in the average nominal wage in 2020, but this was caused by a composition effect, due to the huge decrease in employment in low-wage service industries.

The first story, made up of two story lines and which may be associated with hard-line mainstream economists, is that inflation today is mainly the result of the overly-generous support programs of the government during the course of the pandemic. Its twin story line is that these government deficits have been in large part financed by the central bank, thus leading to an excessive creation of money — an explanation that sounds like a return to monetarism. These twin story lines link current inflation to excess demand, due in part to a scarcity of supply arising from the COVID pandemic. The apparent difficulty of firms to find employees is given as evidence that the economy is running overly close to full employment and potential output, thus justifying the claim of excess demand and the recent restrictive actions of central banks.

The second story, which challenges this excess demand story, seems to be popular among heterodox economists, although it has also been accepted by some mainstream authors who blame industry concentration and imperfect competition. The story has two chapters. In the first chapter, the COVID pandemic and the war in Ukraine, with their detrimental effects on bottlenecks in the supply chains of manufacturing and on agricultural and energy prices, have given a rising impulse on price inflation. But there is a second chapter: this initial impulse has been followed by an additional effect that has sustained or amplified the inflation rate. This additional effect, either called profit inflation or seller’s inflation, is due to greedy firms with some market power taking advantage of the confusion amongst buyers and consumers arising from the distorted information provided by quickly rising prices, thus seizing the opportunity to raise their markup rates. The evidence is said to arise from the brisk increase in profits, the rising profit share in national income, and the higher profit margins observed among non-financial corporations, as first shown by Josh Bivens. Within the Monetary Policy Institute blog, profit inflation has been defended by Ilhan Dögüs for instance, while Isabella Weber and Evan Wasner have provided a detailed description of this second story.

The third story, the one outlined here, takes on board the first chapter of this second story, but it questions the second chapter. While one can certainly acknowledge that some industries such as the oil industry have benefitted from higher profit margins, as explained by David MacDonald for Canada, in a recent @monetaryblog webinar, in general, the rise in profits and the profit share can be explained without resorting to an explanation based on firms taking advantage of the situation and raising markup rates. In other words, this third explanation denies the generalized existence of profit inflation, as also do Matías Vernengo and Esteban Pérez-Caldentey.

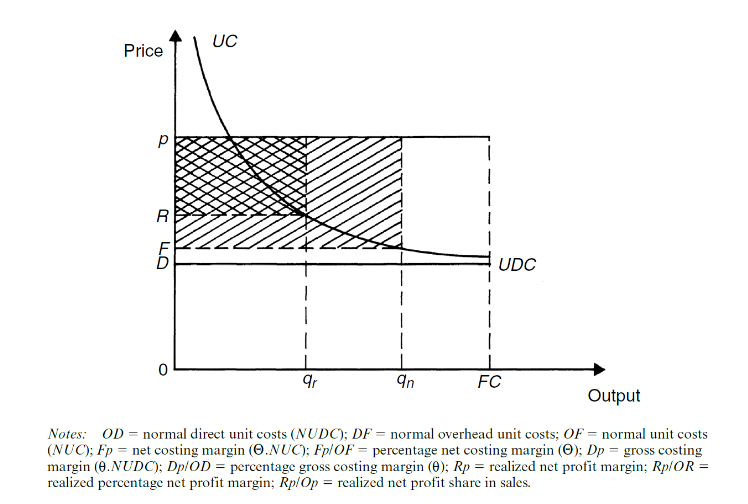

This third story, can be decomposed into two parts, both related to Kaleckian economics. First, consider the microeconomics of the firm. In the post-Keynesian tradition, firms usually operate in an area where marginal costs, or unit direct costs, are constant. Taking into account overhead labour costs and other fixed costs, unit costs are thus decreasing up to full capacity. This means that with a given markup rate over unit direct costs (or with a given markup rate over normal unit costs), profits will be rising for two reasons, as can be seen with the figure below, taken from my 2022 book. First, as firms produce and sell more units, their unit cost drops, and hence their realized profit per unit gets bigger, and secondly since they sell more units, they will make more profits.

At the macroeconomic level, as the economy recovers, the presence of overhead labour costs explains that the profit share in value added will normally rise, despite constant markup rates, and similarly, during a recession, the profit share will decrease and the wage share will increase. This is exactly what happened during the second quarter of 2020, when the wage share rose from 55% to 64%, as shown in the figure below.

Marxists and neo-Goodwinians would have said that there was a 10% drop in economic activity because the high wage share was discouraging capitalists from producing. This is obviously a false conclusion in view of what we know about the cause of the fall in output in 2020. The COVID episode demonstrates that fluctuations in economic activity do generate cyclical changes in functional income distribution. Indeed, Bivens, in the blog mentioned earlier, does recognize that recoveries are normally associated with rising profit shares (without explaining why, however), thus expressing some scepticism about the profit inflation thesis since the profit share rose in 2009–2011 just like it did in 2020- 2022.

The second part of this third story is independent of the presence of overhead labour costs. At the level of the firm, it relies on the fact that approximately only one-third of the direct costs of firms are labour costs, while the rest are intermediate goods and raw materials, which we will call material costs. At the macroeconomic level, the same equations can be used to understand the logic of the argument, but one then needs to assume that these material costs are entirely being imported.

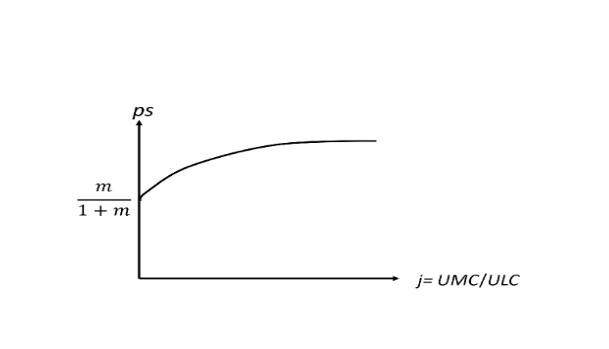

The claim being made here is that the profit share in value added will become higher if unit material costs (UMC) grow faster than unit labour costs (ULC), despite a given level of output and a constant markup rate. This becomes obvious when starting from the (simple) markup pricing equation, as found in post-Keynesian textbooks such as mine (Lavoie, 2022) or that of Eckhard Hein. The more sophisticated normal-cost pricing equation would yield a similar result. Calling j = UMC/ULC, the ratio of unit material cost to unit labour cost, and calling m the percentage markup, the pricing equation is:

When unit material costs rise faster than unit labour costs, the variable j becomes bigger, and thus the price to unit labour cost ratio will rise at the level of the firm. At the macroeconomic level, the share of profits in value added will also rise because this profit share ps is then equal to:

(Imported) unit material costs depend on the technology, the world prices of intermediary inputs or raw materials, and the exchange rate. When the ratio of unit material costs to unit labour costs rises (j rises), with a constant markup rate m, the profit share in value added ps will rise (as shown in the figure above) and hence the wage share will fall.

In their 2022 working paper, Castro-Vincenzi and Kleinman, unsurprisingly from a Kaleckian perspective but surprisingly from their mainstream perfect competition perspective, find that ‘the aggregate labor share mirrors the evolution of the relative price of materials in the US.’. This is particularly the case in materials-intensive sectors. They also show that in countries where there is a rise in the prices of materials and primary inputs, including energy, there is a rise in the share of profits in value added. This observation is consistent with the increase in the profit share which has been observed as a consequence of the covid pandemic and the war in Ukraine. And the Kaleckian markup pricing equation provides a straightforward explanation of this observed direct relationship between the relative cost of materials and the profit share in value added.

Readers may wonder what is left of conflict inflation — the main heterodox explanation of inflation, or rather the lack of it as observed until recently in most countries. Decreases in the wage share occurred in the 2000s (as is illustrated by the figure of the Canadian case) without pressures arising from conflict inflation. Presently, however, the fall in the wage share has been accompanied by a fall in real wages, as nominal wages have not (yet) managed to catch up with prices. But as Weber and Wasner warn, conflict inflation driven by wage catch-up may be the next step in the inflation process, and this might be precisely what central bankers wish to avoid when still hiking interest rates.

Articles on monetary policy, macroeconomics, inflation, and related topics from a heterodox perspective.

679 Followers

https://medium.com/@monetarypolicyinstitute/some-controversies-in-the-causes-of-the-post-pandemic-inflation-1480a7a08eb7

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario