Was there “intensive growth” in Classical Greece and was there something special about its causes ? Was it due to “inclusive institutions” ? This post assesses some claims of the “New Ancient History”. [Retitled from the previous silly title “just what kind of growth was there in ancient Greece anyway?”]

http://pseudoerasmus.com/2015/04/02/ancient-greece-econ-growth/

(1)

Several months ago The Nation magazine published an article by Timothy Shenk called “The Apostles of Growth” which criticised the fixation of the “new historians of capitalism” on economic growth as the decisive difference between capitalism and what ever the hell they think came before. Ironically, that focus on mere growth is no longer really considered by economic historians a key signifier of the Industrial Revolution, precisely because it has been recognised for some time Europe had seen low but compounding rates of growth earlier. Here for example is a view of long-term British growth that’s disputed but increasingly favoured.

In his much-cited essay, “Efflorescences and Economic Growth in World History: Rethinking the ‘Rise of the West’ and the Industrial Revolution“, Jack Goldstone went so far as to say there had been many prolonged episodes of growth in per capita income throughout human history prior to the British Industrial Revolution. The growth rates were low and ultimately unsustained, but they belied the Eurocentric and modernist tendency to view all of preindustrial history as one long Malthusian stagnation. Much the same territory had been trodden by Eric L. Jones in the book Growth Recurring: Economic Change in World History. Both Goldstone and Jones breezily surveyed the history of mankind and managed to find a golden age of “intensive growth” under every rock. Of course they actually cited no data for these.

So I’m happy to report that the “New Ancient History” (NAH) has been working hard to quantify many claims about the golden ages of classical antiquity. In fact, if one were to judge by The Cambridge Economic History of the Greco-Roman World, the names associated with NAH like Scheidel, Morris, Saller, Manning, etc. are obviously influenced by neoclassical economics. These figures are apparently reacting against the orthodoxy originating with Moses Finley, who held that ancient economies were not organised along market principles and therefore modern economic analysis was inappropriate. But Finley’s influence was broken by a younger generation of classical historians influenced by the new institutional economics.

So now Peter Turchin and Daniel Hoyer report that the Stanford classicist Josiah Ober is coming out with a new book called The Rise and Fall of Classical Greece — about the supposed half-millennium of “intensive growth” in ancient Greece and its causes. The first chapter of Ober’s book is available online, and, according to the excerpts already visible on Amazon.com, chapter 4 appears to be basically the same as his 2010 article “Wealthy Hellas“. Ober appears very much a part of the “New Ancient History” wave sweeping the classics.

(2)

“Wealthy Hellas” argues that Greek living standards grew in the period 800-300 BCE, along with the size and number of cities, even as the total population of Greece was multiplied many times. Ober attributes this growth to “inclusive institutions” (though he does not use that exact phrase). Here is Ober’s summary of the evidence for inferring economic growth in Greece:

Only housing size and consumption can truly address living standards, with the rest really just indicators of aggregate economic activity. For the evidence on living standards Ober leans heavily on the work of Ian Morris, best known to the world at large as the author ofWhy the West Rules–For Now.

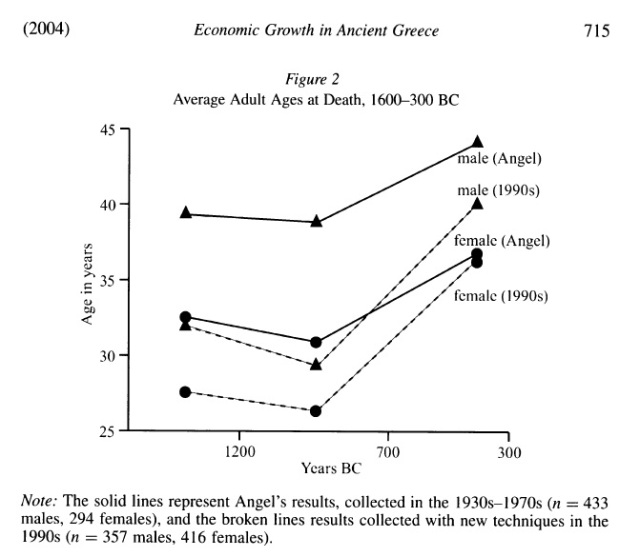

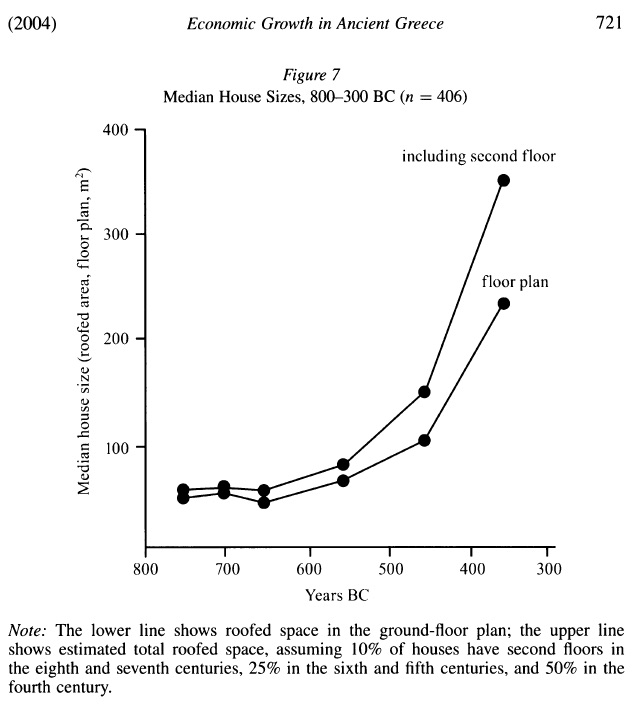

In “Economic Growth in Ancient Greece“, Morris sifts through various kinds of archaeological evidence and seems to establish two things: in the period 800-300BC, the age at death rose and the size of housing went up.

|  |  |

On stature he concludes the skeletal samples are just not numerous enough to make any strong conclusions.

Morris concludes the “improvement in living standards… comes to 0.07-0.14 percent per annum” during the half millennium, or cumulatively 50-100%. And this claim is cited by Ober as part of his overall evidence. But this “estimate” strongly resembles a hot dog — it’s better not to know what went into making it.

[*For the meat slime, see Morris 2004, pp 724-6. Also see the first post in the comments section.]

(3)

Another key piece of reasoning that Ober relies on is the population calculations ofMogens Herman Hansen. Using methods summarised here, Hansen estimates the population of mainland Greece in the 4th century BCE, which was approximately coterminous with the Greece of the late 19th century CE. From this he concludes something quite extraordinary :

My total is 2.6 million,98 but that is the minimum figure. A much more realistic figure would be 3 to 3.5 million.99 Thus defined, ancient Greece is almost identical with Greece as it was after the peace with Turkey in 1880; at the census conducted in 1889 the population of Greece came to 2,188,000 people. Furthermore, that was the maximum number the country could sustain. It was precisely in the 1880s that import of grain began to be a necessity.100 It follows that the population in [the 4th century BCE] was probably between 140 percent and 160 percent of what it was in the late nineteenth century. If it is true that land use and yields were roughly the same in the nineteenth century A.D. as they had been in the fourth century B.C., the inference is that, in the late classical period, about 1 million of the Greeks, and perhaps more, had to live on imported grain that they bought at market. [Hansen 2006, pg 33]

I don’t know how you can assume land use was the same without knowing something about the distribution of land, the ratio of fallow, and the shares of pastoral and arable. But most importantly from an economic point of view, relative prices must have been outlandishly different in the two periods and would have affected what was planted and how much. Wine and olive oil surely bought much more wheat in the late 19th century CE than in the 4th century BCE, because cheap, mechanically threshed wheat from North America and Ukraine was made available to world markets.

Besides, even if it were admitted that land uses were the same in the two periods, the purely ecological reasoning in the passage above from Hansen is backward. IF the same amount of land in 300 BCE could support up to 1.3 million more people than in 1890 CE, that would imply, all things equal, much higher productivity (of land or labour or both) 2400 years ago than in the late 19th century.

Is that plausible ? It would require there had been considerable growth in agricultural productivity in ancient Greece, so that urban labour could engage in other kinds of production and exchange the output for food. On technological change in agriculture in the millennium preceding the 4th century BCE, Ian Morris himself states quite succinctly there was little :

Most Greek technology was fairly basic.64 We should not imagine a monolithic “traditional” agricultural regime in premodern Greece,65 but (except for the introduction of iron around 1100 b.c.e .) in many spheres classical technology was much like what had been available a thousand years earlier. There is no good evidence for improvements in seeds or processing techniques, and, so far as we know, agriculture continued to depend entirely on muscle power. New finds have shown that water mills were commoner in the Roman Empire than had been thought,66 but there is no evidence for extensive use of wind or water power in classical Greece. [Morris & Scheidel pp 117-8]

On the other hand, in The Measure of Civilisation, Morris observes :

The evidence of settlement patterns and excavated farmsteads may indicate a shift between 500 and 200 BCE toward intensively worked blocks of contiguous land, making heavy use of manure and often producing for the market, obtaining yields from dry-grain farming that would not be matched again until at least the nineteenth century.45 Pollen data support this, with peaks for cereal and olive production in the period circa 500– 200 BCE not only in Greece but also all across the east Mediterranean and as far into Asia as western Iran. [pg 72]

Chalk it all up to intensified manuring ?

According to Morris in the paper “The Collapse and Regeneration of Complex Society in Greece 1500-500 BC“, Greek population density tripled or quadrupled or even quintupled between 800 BC and 500 BC. In other words, although the land was supporting many many many more people, the ancient Greek economy was not hitting a Malthusian resource constraint. Land per capita was falling, but income per capita was not. To the contrary, living standards were rising according to Morris. But he apparently does not realise that in order to keep income per capita just constant, even before factoring in the improvement in living standards, there must have been a substantial advance in productivity, whether in yield per hectare of land or in labour productivity.

The higher population density, combined with Morris’s consumption estimates, imply between 450% and 1000% increase in the output per capita of the ancient Greek economy — or 0.3-0.46% per annum over 500 years. That would be faster growth than England in the first half of the 18th century ! Is that believable ? [Edit: I have an addenda post which elaborates on this point.]

Alternatively, even in the absence of major productivity advance in agriculture, it’s possible that the international terms of trade dramatically altered land use in ancient Greece. The olive oils, the wines, and the pottery of the ancient Greeks might have been so highly valued by the non-Greek world that it made sense for Greek farmers en masse to produce less barley and wheat and give more of the land over to olive trees and grape vines. Ober himself recognises that the “imported food had to be paid for somehow”.

But what would have caused this huge demand for Greek goods in the first place ? And is it plausible on the scale implied by the population estimates ? Is there evidence for large-scale conversion of land from subsistence crops to cash crops ? I know Greece imported wheat from the Black Sea region and North Africa, but do the material records attest to the scale of the trade required to produce such surplus populations in Greece ? That’s not addressed in Ober’s article or in Morris.

My larger point is this. Ober, Hansen, and Morris want to use the new population estimates to deduce the economic structure of ancient Greece. But the rather large structural transformation implied by those estimates raise more questions than decide them.

(4)

Or maybe just maybe the population estimates are too high. There might have been growth in consumption per capita as Morris claims, but with more modest population growth.

Then another dimension comes into play: land. Both Ober and Morris have argued that classical Greece broke through Malthusian constraints, i.e., the idea that population and living standards moved inversely in a world of technological stasis. But that simplified Malthusian rule of thumb is only valid under the assumption that the quantity of land is fixed. If land is expanding, it’s possible to have increasing population AND increasing living standards per person, without really anything fundamental changing about the nature of the economic regime.

In presentations of the neo-Malthusian model, the quantity of land is usually held constant. That’s to illustrate that in a world of technological stagnation, there are diminishing returns to labour as population increases on a fixed amount of land, and therefore living standards must fall. But the quantity of land in the model can be varied, i.e., the resource constraint can be relaxed. That may not be obvious from purely verbal or graphical illustrations such as you find in Clark’s A Farewell to Alms, which are intended for undergraduate instruction or popular edification. But in any formal model it is quite obvious.

For example, chapter 3 of Galor contains the bare-bones model of the Malthusian economy, which can easily be calibrated, so that both population and income per worker keep rising, as long as you keep adding extra units of land. (There is a parameter for the response of population to income, and population growth can be less than the growth in land inputs.) I think that’s even implied by Malthus’s own discussion of the New World.

The model also implies that a one-time spurt or limited growth in the level of technology, such as intensified manuring or crop rotation or the introduction of iron implements, can raise per capita income in the short run, even if the long-run outcome is only reverting to the original income and a permanently higher population level.

So with a combination of territorial expansion and limited technological change, this “short run” could easily be a matter of several centuries.

(5)

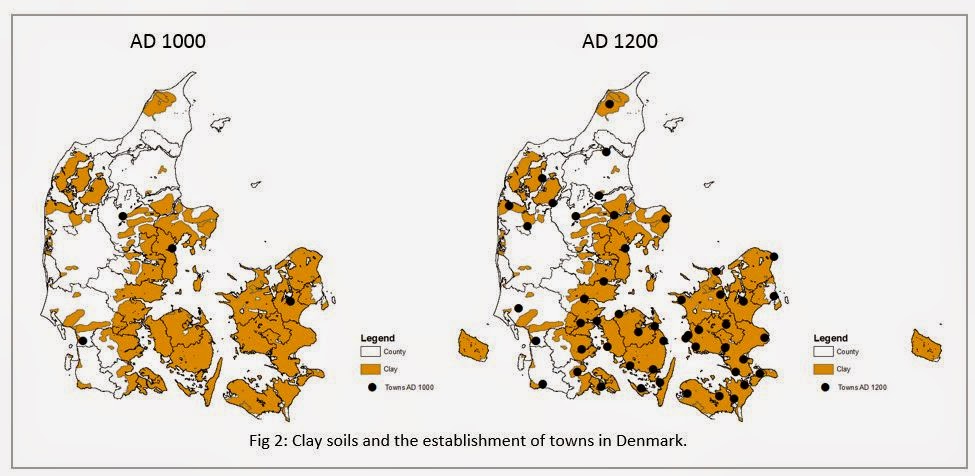

In what is (as far as I know), the first ever statistical test of the mediaeval “heavy plough hypothesis”, Anderson et al. find that the introduction of the heavy plough in the 11th century is associated with approximately 40% of the new towns founded in Denmark in the High Middle Ages. The previous technology — the ard or the scratch-plough — was well-suited to the Mediterranean, but was defeated by the hard clay soils of northern Europe. The purpose of the paper is not about the land input in production, but the implication is pretty clear: the heavy plough opened previously unuseable land to exploitation.

I cite this only because Goldstone mentions the “mediaeval economic revolution” in the effluorescence essay as another probable example of “intensive growth”. Yet it’s a pretty straightforward case of land expansion.

So maybe the golden age of classical Greece was also land-driven ? If, as we have thought for more than a century now, the Greek world had been depopulated during the Dark Ages following the collapse of Mycenaean civilisation, then it’s possible the economic expansion of the 9th-4th centuries BCE was mostly a re-colonisation or re-population process. The new, archaic-era Greek settlements in Macedonia, Thrace, Asia Minor, the Black Sea region, southern Italy, and southern Gaul would represent the emigration of surplus populations in “core” Greece. Then the “effluorescence” would have petered out because this process had hit a political or geographical limit.

One need only compare the territorial extent of the Mycenaean world at the end of 1100 BCE with the revived Greek world circa 550 BCE :

|  |

The Greek economic efflorescence, then, would seem decidedly non-magical — a product of land and dung.

(6)

But does all this matter ? Yes. Ober speculates about the institutional causes of ancient Greek economic expansion, with much sterile theorising about egalitarian institutions, human capital, transaction costs, risk management, incentives for cooperation, etc. The second half of the “Wealthy Hellas” article reads far more as though a caricature of theory has been substituted for scanty evidence, than theory is guiding the search for evidence.

Maybe land-and-dung expansion does not really require a fancy institutional explanation. Territory expanded, land yields rose, and people have always traded their surpluses. Why invoke “inclusive institutions”, as Ober effectively does, for something so mundane ? Perhaps the seminal cultural accomplishments of classical Greece bias some of us to look for “special” causes of the expansion.

Note, this is not an argument that political economy or “institutions” play no role in the rise and decline of economies. But in this particular case, so little seems established about the descriptive statistics, let alone the “growth accounting”, of Greek economic expansion in 800-300 BCE that it’s premature to be speculating about its institutional causes.

Postscript: The causes of Greek economic growth may have been “ordinary”, but certainly their effects somehow were not. Ober is quite right that the peculiarly egalitarian institutions of the ancient Greeks cry out for an explanation.

Here’s a possible scenario. The collapse of Mycenaean civilisation in the 12th century BCE allowed a “reset” on Greek political evolution, a kind of institutional creative destruction. In the absence of the Late Bronze Age collapse, some Pelopponesian city-state like Mycenae itself or a mainland state like Thebes might have consolidated a circum-Aegean state 800-900 years earlier than Athens would attempt or Macedon would ultimately accomplish. This “reset” prevented the creation of a centralised state in the Aegean for almost a millennium. The population recovery from the Dark Ages was accompanied by land tenure based on small holdings, as we would normally expect in the course of proto-political development with village cultures. This led to the relatively egalitarian city-states of citizen-farmers when Greek poleis started emerging from obscurity again in the 9th century. Hence, Ober’s “rule egalitarnianism”. An effect, not a cause, of economic growth.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario